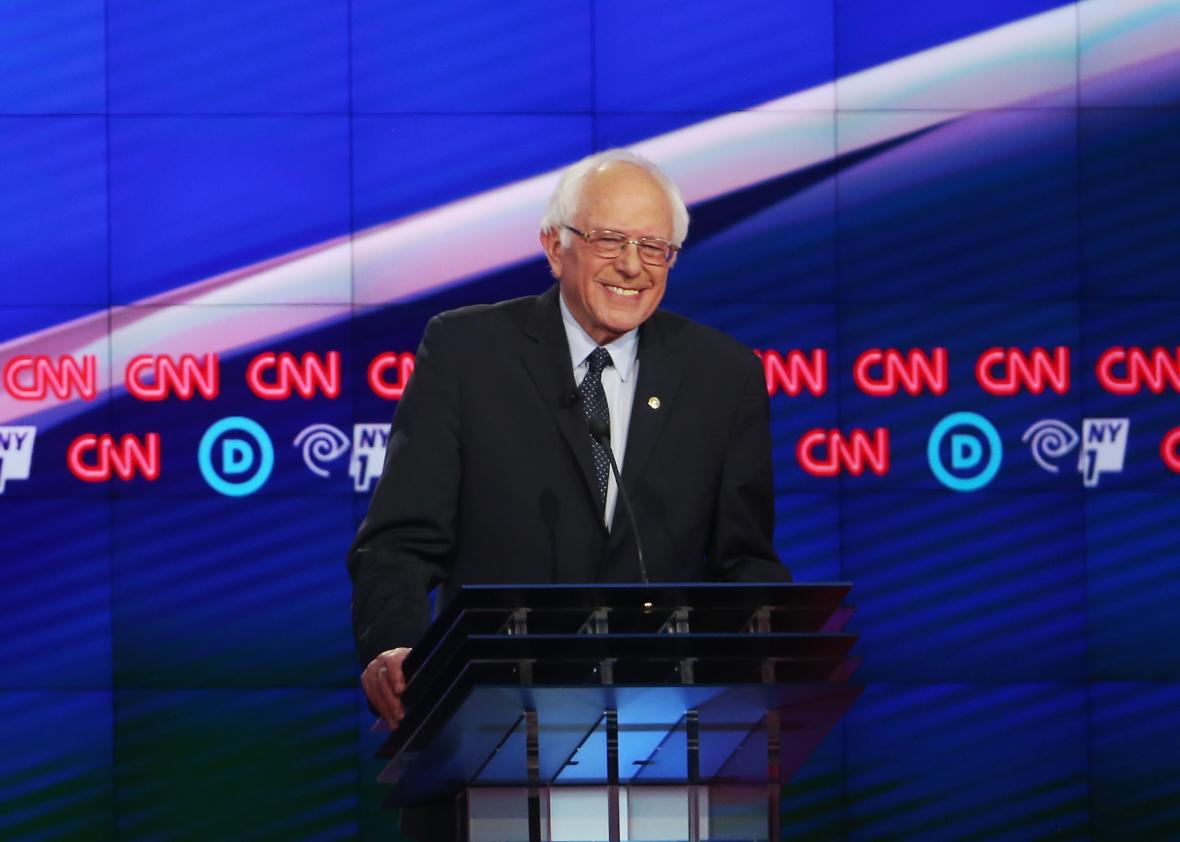

“History has outpaced Secretary Clinton,” said Bernie Sanders, the 74-year-old socialist senator from Vermont who often appears to have stumbled out of the pages of a crumbling paperback history of 1930s radicalism. But appearances can shortchange as well as deceive: From the moment that his campaign kicked into high gear more than six months ago, Sanders has captured the radicalized spirit of a Democratic Party that is increasingly attentive to the appeal of economic populism and to the realities of racial injustice. During CNN’s Democratic debate on Thursday night, while the candidates ricocheted between discussions of global warming as the primary threat to America and whether to raise the minimum wage to $12 or to $15, it was hard not to feel that Sanders had won a battle almost as large as the race to be the 2016 nominee.

“I want white people to recognize that there is systemic racism,” Clinton stated Thursday night in one of many statements that would cause a time-traveler from the 1990s to stare with open-mouthed astonishment. Indeed, the debate functioned as a fascinating window into Democratic politics in 2016. Even a mere eight years ago, Obama and Clinton often struggled to outflank each other on the right. (Think of the skirmishes over the individual mandate.) But on nearly every domestic issue, both candidates went left, strongly so, and from health care to college tuition to Social Security, Clinton played on Sanders’ turf. Even her critiques of Sanders’ spending focused not on the deficit but on Sanders’ general sloppiness with numbers.

Most of the debate thus settled into a routine in which both candidates used their time to fortify their progressive bona fides. Sanders’ weakest issue remains gun control, where his record is relatively moderate. Clinton still makes a dog’s breakfast of any answer regarding her speeches, such as the one to Goldman Sachs. (Sanders needs to develop a better response to the perfectly reasonable question of how Clinton’s donations and Wall Street connections have influenced her as a policymaker. He might’ve mentioned bankruptcy reform.) And everyone in the Brooklyn audience cheered anything even resembling an applause line—“Let’s talk about judgment”—and I was reminded yet again that the crowds are the most annoying thing about these debates not named Wolf Blitzer.

The one area where the pattern shifted was foreign policy. Clinton remains stuck in the 1990s paradigm that she has otherwise discarded, at least rhetorically. On Libya and Syria, Clinton took a more hawkish line, as she did as secretary of state, and was (for her) surprisingly unfocused and even a little shameless. Her claim that the United States did plenty to provide for Libyans after the NATO bombing campaign is, er, questionable.

The debate lingered for a long moment on the subject of Israel, and the more Clinton talked, the more she sounded like a back issue of Commentary. She blamed the Palestinians for the failed Camp David negotiations in 2000. “If Yasser Arafat had agreed with my husband at Camp David in the late 1990s to the offer that Prime Minister [Ehud] Barak put on the table,” she said, “we would have had a Palestinian state for 15 years already.” Sanders, however, mounted a stronger, more rousing defense of Palestinian rights than I can remember hearing from a major presidential candidate. There were real differences to dwell on here, although Bernie’s suspension of his progressive new Jewish outreach director, announced shortly before the debate amid considerable hue and cry, suggested that the Democratic Party isn’t as eager to follow him to the left on Israel as it has been on domestic issues. (Still, the fact that the subject was debated so heartily is itself a sign of at least some change within the Democratic Party.)

The irony of his campaign is that the septuagenarian Sanders is probably four or eight years ahead of his time, rather than behind it. In some ways Sanders was lucky in his opponent. He wound up getting paired against someone who happens to be on the wrong end of the prevailing trends in the party—hawkish; friendly to Wall Street; an almost perfect embodiment of that otherwise nebulous term, the establishment.

Despite these advantages—not to mention a fundraising prowess that must surprise even him—Sanders is still facing an almost impossibly narrow path to the nomination, and this debate was unlikely to widen it much. Clinton’s support among minority voters, not to mention the large margins she ran up in many Southern states, are almost certain to ensure her victory. But she is not only a different candidate and political figure from the Hillary of 2008; she is significantly, ideologically distinct from where she was in 2015, and in the general election she will likely be running on a platform as progressive as the Democratic Party has had in many years. Clinton will surely move quickly and decisively to the right once she officially vanquishes Sanders, but the triumph of the Bernie insurgency is that to get back to the center now, she has so much farther to run.