For the past few months, the fate of the republic, or at least of the Republican Party, has seemed to hang on Marco Rubio. Even now, despite all the evidence to the contrary, that remains the desperate view of a swath of the party’s eminences grises and billionaire benefactors. They still imagine themselves, and their candidate, as the noble protagonists in a twilight struggle against the forces of proto-fascism and yokelism. Only by spending wildly and forcing the nominating process into the backrooms of a brokered convention can they save their party from a descent into unprocessed insanity.

Marco Rubio’s whole career had been building to this moment. He was long viewed as the party’s salvation—or as the cliché goes, he’s the Republican Obama. On paper, he made for a compelling messiah: demographically useful, salable to the ultras yet charismatic enough for a general, and, on top of everything else, intellectually adept. Of course, that elite faith in Rubio now seems comically misguided. He looked both puerile and ineffectual—like Little Marco, actually—in his flailing efforts to take down the bully.

Donald Trump’s hostile takeover of the party is a pretty fair summation of the recent history of the Republicans, the volcanic explosion of all the nasty sentiments that the party nurtured over the decades. But it’s also telling that Marco Rubio came to represent the establishment’s idea of sanity. Despite his sheen, there’s nothing remotely moderate about Rubio. It would be a mistake to think of him as a denizen of the center-right. His agenda, both domestic and foreign, is at least as right wing as Ted Cruz’s program, if not more. His vision lacks much of Donald Trump’s overt cruelty, but in its own way it would terrifyingly remake American government. As the establishment mounts a final, doomed effort to prop up the Rubio campaign, it’s worth examining the object of their devotion and what he reveals about his backers. Rubio would have easily been the most radical nominee in Republican Party history. Where John McCain and Mitt Romney faked some of their severely conservative campaign forays, Marco Rubio is a true believer. He became the face of an establishment that has drifted so far to the right that it might never return.

“No one’s going to force me to stop talking about God.”

Marco Rubio felt like he had caved to the forces of political correctness. During his long tenure as speaker of the Florida House, he bit his tongue and betrayed his heart. But on his way out the door, he was determined to speak out. “It had taken me too long,” he later wrote in his memoir, An American Son. For his valedictory address in the fall of 2008, he would turn the dais into a pulpit and deliver the sermon he regretted never preaching. “God is real,” he declared, “God is real. I don’t care what courts across this country say, I don’t care what laws we pass—God is real.”

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

The address culminated in a rousing peroration about the necessary presence of religion in the public sphere. “God doesn’t care about the Supreme Court of Florida,” he said. “He cares about them. But he doesn’t care about their rulings. And he doesn’t care about the Supreme Court of the United States. You can’t keep him out.”

The speech wasn’t a stray musing. Earlier that year, Rubio went to work on behalf of Mike Huckabee’s presidential campaign—hardly the expedient choice for a career-minded politician from South Florida. (Jeb Bush, by contrast, had endorsed Mitt Romney.) Huckabee was an evangelical preacher who touted himself as a “Christian Leader” with a “biblical worldview.” A YouTube clip shows a boyish Rubio leading a group of placard waving volunteers on a New Hampshire street corner. “Quite frankly this has become more like a movement,” he tells the camera. Two years later, the very same home-schoolers who formed the backbone of the Huckabee campaign provided the earliest foot soldiers for Rubio’s 2010 Senate bid.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Rubio’s religious life has been unfairly tagged as evidence of his desire to please everyone. It’s true that he’s hardly charted a linear path to church. As a child in Las Vegas, he enthusiastically immersed himself in Mormonism—reading canonical texts, visiting the holy sites in neighboring Utah, and becoming a fanboy of the Osmonds. Back in Florida, he urged his family to return to Catholicism with the same conviction. “Football and religion. Those were his things,” his cousin Michelle told Rubio’s biographer, Manuel Roig-Franzia.

In recent years, he’s dialed up his devotion, while still leaving his doubters with the impression he’s hedging his bets. “I have come home to Rome,” he has said. “One of the great treasures of the Catholic faith is the ability to go to Mass everyday.” It’s a ritual he has performed with that precise regularity for long stretches of his adult life. He subscribes to Magnificat, a magazine that supplies him with daily meditation. And he has boasted about his use of contraception, or lack thereof: “I can tell you that none of my children were planned.”

But while Rome is home, he’s maintained a weekend cottage in the Southern Baptist Church. On Saturdays he takes communion; on Sunday he attends Christ Fellowship, his wife Jeanette’s church of choice. The decision might be theologically tricky to justify, but Rubio explains it like this: “I don’t think you can go to church too often or spend too much time in fellowship with other Christians, whatever denomination they confess.”

In his telling, Rubio is a particularly receptive pilgrim. He seems to be always receiving messages from the Lord—they appear regularly in his self-effacing memoir. A job offer comes his way, just as he’s on his knees praying for God’s help. In the early flailing days of his Senate campaign, he discerns signs from God that urge him forward. “I felt as if God were sending me a message.” He hears that message in the singing of 3-year-olds and sees it on a keychain he serendipitously finds on a table. It contains a laminated verse from the book of Joshua: “I’ve commanded you to be brave and strong, haven’t I? Don’t be alarmed or terrified, because the Lord your God is with you wherever you go.”

We’re accustomed to Republican nominees mouthing the slogans of the culture war, without fully believing them or soft-pedaling them with an eye toward the November electorate. When George W. Bush ran his evangelical friendly campaign, he told his story of spiritual conversion and spoke in the rhetoric of uplift, rather than dwell on the prospects of social apocalypse. Rubio, by contrast, is a happy culture warrior, or perhaps a glum one. “Without faith at the core of our society, you fall into an era of moral relativism,” he told the Center for Arizona Policy, a group that supports conversion therapy for gay kids. When asked about the Obergefell decision enshrining gay marriage, he told the Christian Broadcasting Network: “We are clearly called in the Bible to adhere to our civil authorities. But that conflicts with also our requirement to adhere to God’s rules. So when those two come in conflict, God’s rules always win.”

Though Rubio remains the favorite son of the GOP establishment, on the social issues, you couldn’t slide a sheet of cigarette paper between him and Ted Cruz. They would both restrict abortion so thoroughly that they wouldn’t exempt victims of rape or incest. “I personally believe you do not correct one tragedy with a second tragedy,” Rubio argues. This puts him in stark contrast with George W. Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney. When it comes to gay rights, his stance extends far beyond denunciations of the court’s marriage decision. He has stridently opposed gay adoption—which Mitt Romney supported—and he has fought anti-discrimination legislation. “I’m not for any special protections based on orientation.” He has promised to reverse Obama’s executive orders committing the country to non-discrimination. “On my first day in office, they’re gone.”

Like Cruz, he believes that Christianity is on its way to being criminalized by the commissars of tolerance. These are arguments that he crafts with hyperbolic fervor, far more than the art of the pander demands. “We are at the water’s edge of the argument that mainstream Christian teaching is hate speech, because today we’ve reached the point in our society where if you do not support same-sex marriage, you are labeled a homophobe and a hater. So what’s the next step after that, after they’re done going after individuals? The next step is to argue that the teachings of mainstream Christianity, the catechism of the Catholic Church, is hate speech. That’s a real and present danger.”

“Only One Nation on Earth …”

Marco Rubio struggled to find his place in the world. As a kid, he repeatedly asked to be transferred to new schools, never quite settling comfortably. When his family moved from Las Vegas back to Miami, he was mocked for his “American” accent. His fellow students deemed him a gringo. Rubio felt “that he didn’t belong anywhere,” McKay Coppins has reported.

Solidity was a precious commodity, and he clung to his paternal grandfather, Pedro Victor García. For much of his adolescence, Rubio sat at his feet and studied. Pedro would perch in an aluminum chair on his front porch, smoke a cigar, and launch into soliloquies for Marco’s benefit. During the summers, Marco would listen for two hours at a time. “My grandfather was my mentor and my closest boyhood friend,” Rubio would later recount. It’s easy to see why Rubio would have taken so much pleasure in these talks. They were passionate and learned. Pedro was a reader with strong opinions.

For the most part, these were the opinions of a Cuban exile. Pedro was a hardliner in the Cold War, who considered the United States the indispensable protector of light and good in the world. In his view, the global fate of freedom hinged on the willingness of the United State to play its allotted role. By the fifth grade, Rubio had internalized his master’s teaching so thoroughly that he wrote a paper praising Reagan for saving the American military from years of malign neglect by the feckless Jimmy Carter.

When Marco Rubio arrived in the Senate, he made these ideas the core of his political identity. They weren’t especially fashionable at the time. The Tea Party represented a backlash against the George W Bush era. Rand Paul aspired to be the defining politician of that era and his skepticism about the use of force abroad seemed to reflect the swelling hostility to neoconservatives and their idealistic interventionism. Rubio made it his mission to be the spokesman for the backlash against the backlash.

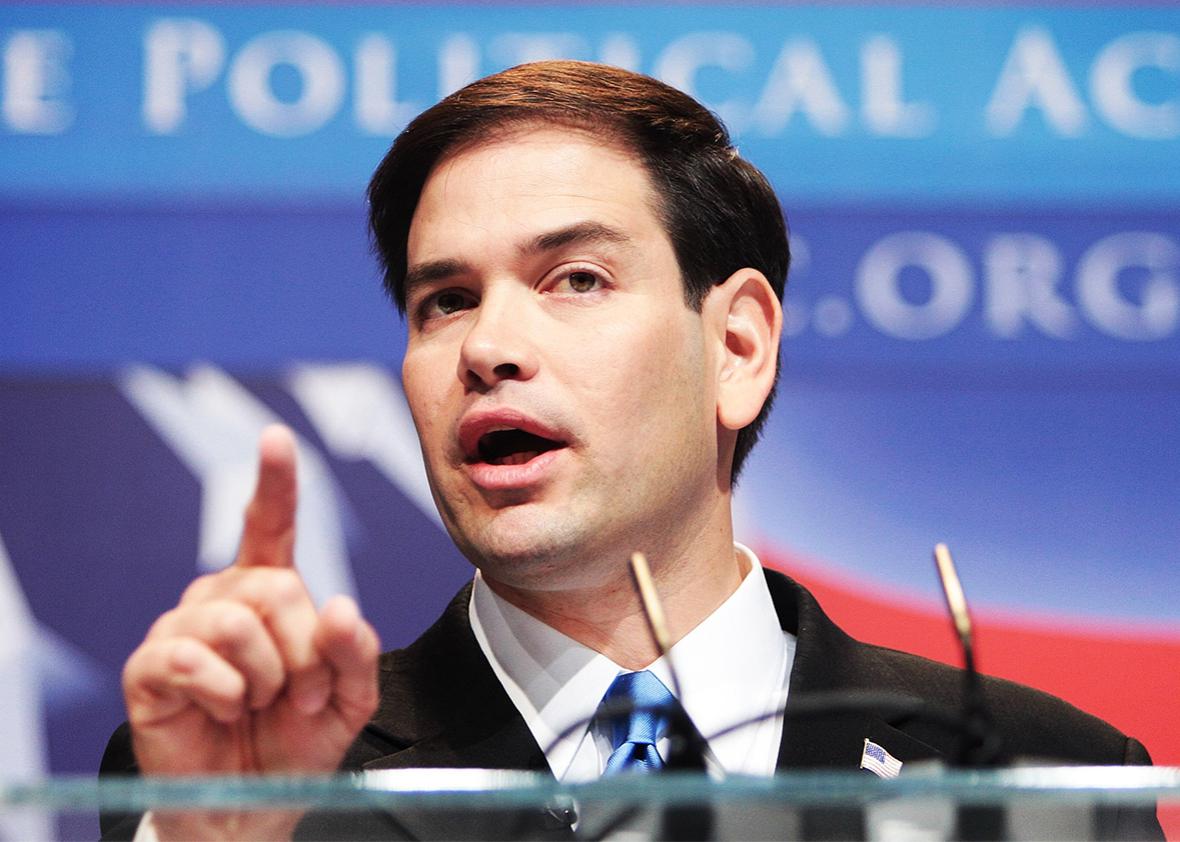

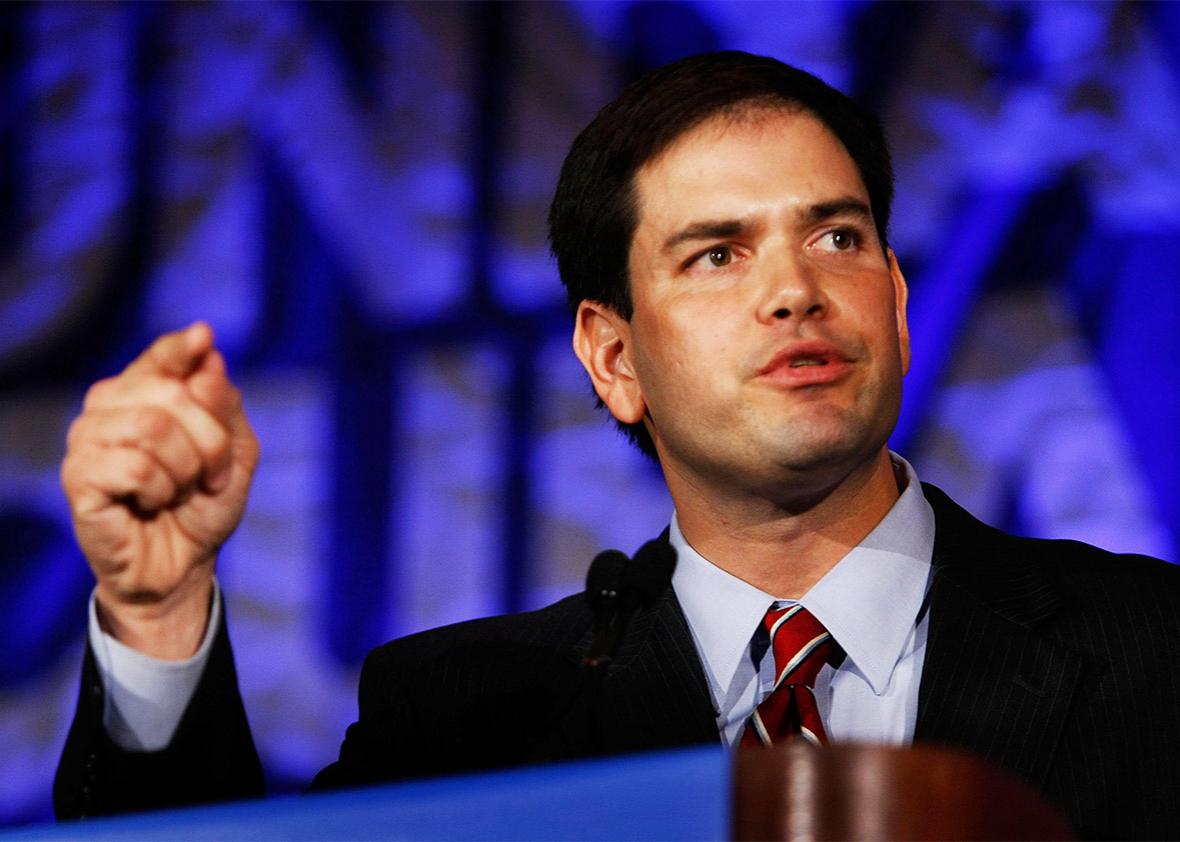

Rubio surrounded himself with the neoconservatives who had fallen out of favor. He sought out Robert Kagan and Elliot Abrams for counsel. Joe Lieberman became a mentor; the two co-bylined an op-ed urging the toppling of Qadaffi in Libya. For his foreign policy adviser, Rubio hired Bill Kristol protégé Jamie Fly, who advocated a preemptive bombing campaign against Iran. It’s easy to see why they gravitated to Rubio. He mastered his subject with wonkish depth and ideological passion. And when he spoke about America’s role in the world, he could sound just as lyrical as his grandfather: “There is only one nation on Earth capable of rallying and bringing together the free people on this planet to stand up to the spread of totalitarianism,” he bellowed at last year’s CPAC gathering of the faithful.

Win McNamee/Getty Image

What irked Rubio most was that America had shelved its commitment to freedom in the Western hemisphere, especially in its campaign to dislodge Castro. Well before Obama restored relations with Cuba, Rubio worked behind the scenes to punish public officials who betrayed any hint of softness toward Castro. He blocked Jonathan Farrar, the former head of the U.S. Interests Section in Havana, from becoming the ambassador to Nicaragua. Rubio scuttled his nomination on the basis of petty offenses. Farrar had had the temerity to permit State Department officials to stay at the state-owned Hotel Nacional, rather than in a U.S.-owned guesthouse. Now that Cuba has reopened the American embassy in Havana, Rubio has emerged as the face of the opposition. He would stomp on this policy, ending diplomatic relations and imposing a new batch of sanctions.

Unlike Trump and Cruz, who have disavowed large chunks of George W. Bush’s foreign policy, Rubio still believes fervently in the necessity of nation building. Where his rivals speak with the cold inflections of realism Rubio drapes his foreign policy in idealistic commitment to the promotion of democracy and human rights. Of course, Rubio has issued the requisite disavowal of militarism—“I don’t want to come across as some sort of saber-rattling person”—but he also promises a foreign policy that would make conflicts more likely. “I will use American power to oppose any violations of international waters, airspace, cyberspace or outer space,” he has said. Rubio has promised that he would declare the Iranian nuclear deal illegitimate. To fight ISIS, he wants to send American soldiers into conflict—a step none of his remaining rivals favors. He has also suggested sending Special Forces to Yemen, where they could lend a hand to Saudi Arabia’s bloody sectarian intervention. Rubio is willing to commit these resources because he considers the conflict in the Middle East downright apocalyptic: “This is a clash of civilizations. There is no middle ground on this. Either they win or we win.”

“My parents lost their country to a government, I’m not going to lose mine.”

Nobody would have described the young Marco Rubio as an intellectual. College was a long, painful awakening from his never particularly achievable dream of becoming a professional football player. Despite his own academic indifference, Rubio the politician has gravitated to intellectuals. He ascended in Florida politics under the wing of Jeb Bush, a joyous enthusiast for Big Ideas. As he prepared to become Florida speaker, he held “Idearaisers” across the state, sessions with voters to brainstorm new initiatives. During his first year in government, he committed himself to learning the conservative catechism. He read Atlas Shrugged twice in quick succession.

As a senator, Rubio has cultivated the most self-consciously intellectual wings of conservatism. More than any of this cycle’s presidential candidates, he likes to let you know the big book tucked under his arm. For a time, Rubio proudly toted Henry Kissinger’s Diplomacy everywhere he went and trumpeted his tutorial with the former secretary of state: “I listened to him like a student.” The acknowledgements for his book American Dreams is a directory of the young-ish policy entrepreneurs with greatest cachet on the right. It name checks: Yuval Levin, Ross Douthat, Oren Cass, Reihan Salam, the architects of reform conservatism.

There were both personal and political reasons for Rubio to gravitate to the reformicons. These intellectual gurus wanted to liberate the Republican Party from its slavish devotion to tax cuts for the rich, reorienting its policy priorities to the working class. There was an implicit critique of the hard libertarian edge of the Tea Party in much of their critique—and more explicitly a brutal analysis of Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign, which was so easily tagged as plutocratic.

For Rubio, the reformicon program was an extension of his own empathetic paycheck-to-paycheck narrative. It made him a creature of his times, rather than a parrot of crusty nostrums, and it allowed him to turn his struggles with debt into a talking point, as opposed to a skeleton in his closet. Of course, there was no way that he could (or would want to) directly confront the problem of income inequality, given what he’d learned from Ayn Rand and his intention to win the nomination of Charles and David Koch’s party. But he could at least gesture toward the problem. His tax plan featured a $2500-per-child tax credit, a benefit for families of modest means.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

This nod to inequality won him the plaudits of pundits. And they were right to see his plan as redistributionist—they just emphasized the wrong direction in which the money flowed. After complaints from mainline conservatives about his plan’s insufficient slashing of rates, Rubio has redoubled his efforts and proposed a gargantuan cut, far beyond anything George W. Bush ever contemplated. Three times as large, in fact. It would eliminate all taxes on capital gains, dividends, interest, and inherited estates, thereby reducing federal revenue by 25 percent and padding the plutocracy. Jonathan Chait tabulates it like this: “This isn’t “buy a new BMW every year” type money for the one percent. It’s more ‘Scrooge McDuck swan dive into a pile of gold’ type money. Paris Hilton’s descendants would be able to go several generations deep into the future without anybody working a day in their life.”

* * *

Why did Rubio receive a relative pass for his deeply held radicalism? He wielded the same biography that brought him to these hardline positions as a force field. His life story became the stuff of marketing. He harped on his youth in order to separate himself from the tired old establishment. His working-class roots were the populist plot points that he used to sell less-than populist policies. “If I’m our nominee, how is Hillary Clinton gonna lecture me about living paycheck to paycheck?” In other words, he presented the most vapid version of his life’s story—a version that scrubs the more contentious truths about his life story, so that both conservatives and moderates can see whatever they find most comforting.

Marco Rubio’s demise will be read as the sad death of establishment-minded conservatism. The obituaries will bemoan the collapse of the center; they will express panic at the helplessness of reason in the face of powerful new extremes. But where Donald Trump, the vessel of white nationalism and enemy of free speech, poses one terrifying new threat to the republic, Marco Rubio represented another. He took the primary tenets of the George W. Bush presidency and fattened them up or pushed them further to the ideological extreme. Where Donald Trump would face internal resistance to his program, Marco Rubio would have delivered his to a unified party with the conviction of someone who really, truly means it. That his political promise has ended in such crushing humiliation is reason to cheer.