“If you spend time in hardscrabble, white upstate New York, or eastern Kentucky, or my own native West Texas,” writes Kevin Williamson for National Review, “and you take an honest look at the welfare dependency, the drug and alcohol addiction, the family anarchy. … The truth about these dysfunctional, downscale communities is that they deserve to die.” His colleague David French echoed the assessment. “Simply put, Americans are killing themselves and destroying their families at an alarming rate. No one is making them do it. The economy isn’t putting a bottle in their hand.”

In the past, this is how conservatives have talked about struggling blacks. If inner cities and rural black communities were poor and dysfunctional, it was because of cultural deficiencies, not broad economic problems. With more effort, went the argument, they could overcome economic isolation and social stigma. And the evidence was success among low-income white Americans who’d overcome their station.

But now, more whites than ever are sinking toward the bottom, living in the same conditions that have faced black Americans for decades. And suddenly, conservatives are talking about them in the same way. We’ve seen this dynamic before.

“The chief characteristic of Rag Tag and Bobtail, however, is laziness. They are about the laziest two-clogged animals that walk erect on the face of the Earth,” wrote Alabama lawyer and secessionist Daniel R. Hundley in Social Relations in Our Southern States, a widely cited volume published on the eve of the Civil War. “Rag Tag and Bobtail” is Hundley’s moniker for the poor whites of the South, whom he also calls “poor white trash.” He describes them as “working habitually in company with Negroes,” and in some sense as being black themselves. “Even their motions are slow, and their speech is a sickening drawl, worse a deal sight than the most down-eastern of all the Down-Easters while their thoughts and ideas seem likewise to creep along at a snail’s pace. All they seem to care for, is, to live from hand to mouth; to get drunk, provided they can do so without having to trudge too far after their liquor,” Hundley wrote. “We do not believe the worthless ragamuffins would put themselves to much extra locomotion to get out of a shower of rain; and we know they would shiver all day with cold, with wood all around them, before they would trouble themselves to pick it up and build a fire.”

Hundley is just one man, but there’s no question these attitudes were common among the Southern fancy class. In one euphemism-rich passage in an 1854 treatise, Henry Hughes, a Confederate colonel and sociologist, wrote in aspirational terms of a system of American slavery in which all races participate, a sort of “I Have a Dream” speech in reverse: “Warranteeism without the ethnical qualification is that to which every society of one race must progress.”

Among members of the elite, the teetering of the social structure established by slavery was understood in part as a sort of blackening of poor white people. There was something inherent in this class of white people, the thinking went, that accounted for—and justified—their lowly station and their “dysfunctional, downscale communities.” Class anxieties had been racialized.

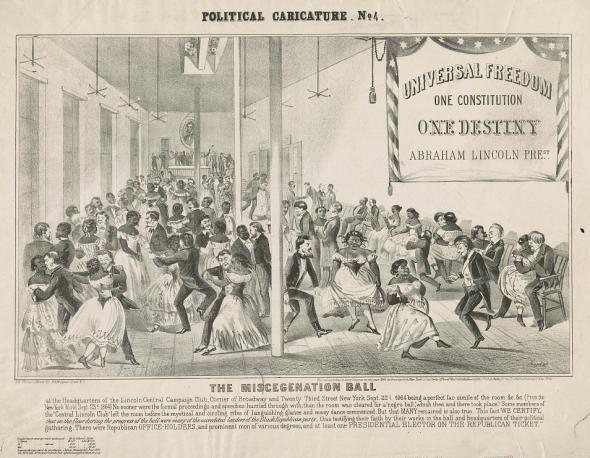

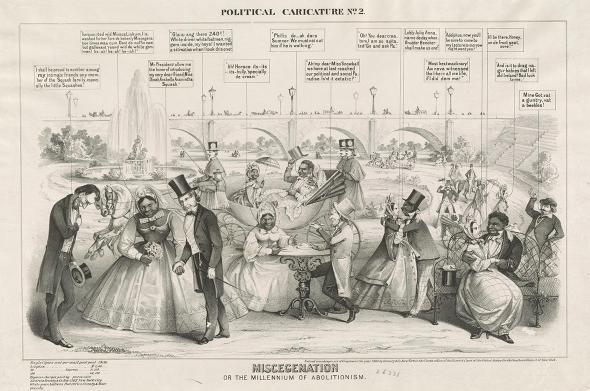

The fear among white laborers—North and South—had less to do with a flattening of the lower social strata than it did with their outright inversion. This was put to vivid political use. In the lead-up to the 1864 presidential election, the New York World—one of the most pro-Southern papers in a generally pro-Southern city—published a series of anti-Lincoln stories, editorials, and lithographs. One of them was titled “Miscegenation Ball.”

In the top right corner of the illustration was a banner that read “Universal Freedom. One Constitution. One Destiny.” In the background, illustrators placed a portrait of Abraham Lincoln. And in the foreground, a mixed-race group of white men and black women danced and celebrated. The message was simple: If you re-elect Lincoln, you’ll make miscegenation the law. A later lithograph, titled “Miscegenation or the Millennium of Abolition,” was more explicit. Viewed from left to right, it depicted President Lincoln bowing to a mixed-race couple (a black woman in dress and a white man in formal wear), a black man and his black wife riding a carriage drawn by a white man, and two black men, each embracing a white woman. Again, there’s no question of the message: Under President Lincoln, this is America’s future.

It’s clear that, with these cartoons, the New York World was playing on the disgust of its white readers. But it was also playing on an old fear. Fear that America would become Saint-Domingue writ large. Fear that abolition would bring a world turned upside down, as the hierarchy that placed whites on the top and blacks at the bottom collapsed under the strain of war and emancipation. Lincoln won re-election (thanks to a massive margin with Union soldiers that required no small amount of coercion and intimidation), but this racist fear would remain, grow, and curdle into violent anger. Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was a Confederate sympathizer throughout the war. But he made his fateful choice upon hearing Lincoln voice support for black suffrage. “That means nigger citizenship. Now, by God, I’ll put him through,” cursed Booth as he stood in the audience. “That is the last speech he will ever make.”

In the aftermath of the Civil War, this fear of racial inversion would drive ex-Confederates to form anti-black militias and vigilante groups, devoted to terrorizing emancipated black Americans and re-establishing the old hierarchy. What Southern whites called “Redemption” in the 1870s and 1880s, blacks understood as an attempt to re-enslave them, or at least to keep them in conditions akin to slavery.

All of this gets at one of the key ideas in my look at Barack Obama and the rise of Donald Trump. The ascension of a black American to the nation’s most prestigious office—coupled with the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression—produced a jolt of material and racial anxieties for millions of working white Americans. In the past, whiteness brought a measure of social stability. Even when poor, whites would never be at the bottom of America’s hierarchy—they would never be niggers. Suddenly, that wasn’t as true, as the downturn destroyed jobs and brought “inner-city” social ills to white rural and suburban enclaves. Moreover, the visible rise of a nonwhite elite (both black and Latino) challenged notions of any kind of social superiority. Now, perhaps, they were at the bottom, or close to it.

This isn’t the same fear and anger that put Lincoln in the grave and stopped Reconstruction from reaching its potential, but it’s related. It rhymes. And while our period of economic crisis and rapid racial change is different from previous ones, it has—like its forebears—sparked a similar movement of the anxious and resentful, drawn from working- and middle-class whites who view themselves as a bulwark against the seemingly idle and dependent, even as conservative elites begin to view them in the same way. We had Redemption. We had the second Ku Klux Klan. We had George Wallace. Now we have Trump.

The difference now is that this group of whites isn’t as large as it was. And if the GOP weren’t so reliant on white voters—that is, if it weren’t such a dysfunctional party—Trump might have stayed at the margins. But the GOP’s extreme conservatism—inculcated and heightened in the state houses and governors’ mansions where it has complete control—and contempt for basic norms of politics has given Trump (and Trump-like figures) space to grow and flourish. And while Trump is still a long shot for the presidency—the larger American electorate is different from the Republican Party base—that doesn’t mean he can’t do real damage to our political institutions. With the outbreak of violence at Trump events around the country—spurred on by the candidate himself—it’s already happening.

It’s hard to know where this leads. But if the past is any guide, this backlash of anger and nativism will get fiercer before it burns out—if it ever does. One thing is clear, however: These voters aren’t entirely wrong. The inversion of status, or at least a dramatic decline in status, is happening. National Review did us the service of making that explicit. The big question—perhaps the single largest question of American history—is whether this will inspire empathy and fellow feeling with minorities or just become tinder for the ongoing racial reaction.