Let’s assume that Donald Trump secures the GOP presidential nomination, as seems more likely than not. How should anti-Trump Republicans respond? Trump’s rivals, Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, and John Kasich, have all pledged to support the Republican nominee. This has put Rubio and Cruz in particular in an awkward position, as both have warned that Trump, among many other bad things, is a man who cynically preys on the hopes of the weak and vulnerable. Unless Rubio and Cruz are willing to concede that these charges are overblown, it seems more than a little odd that they’d be willing to put them aside come November. Granted, they may well believe that a Democratic victory would be worse than a Trump victory. But there are many other Republican voters—tens of millions of them, potentially—who will disagree and who will hold their noses and vote for a Democratic presidential candidate, will choose to abstain, or will vote for a minor-party candidate.

It is this last possibility that I find most intriguing. In the new issue of National Review, Ramesh Ponnuru argues that Trump’s conservative opponents must at least consider backing a third-party conservative. “[T]he most important reason to back a conservative third-party run is not to affect the outcome of the November elections,” writes Ponnuru. “It’s to demonstrate that conservatism stands for something better than Trump.” But who would be willing to take on the thankless task of mounting a third-party challenge?

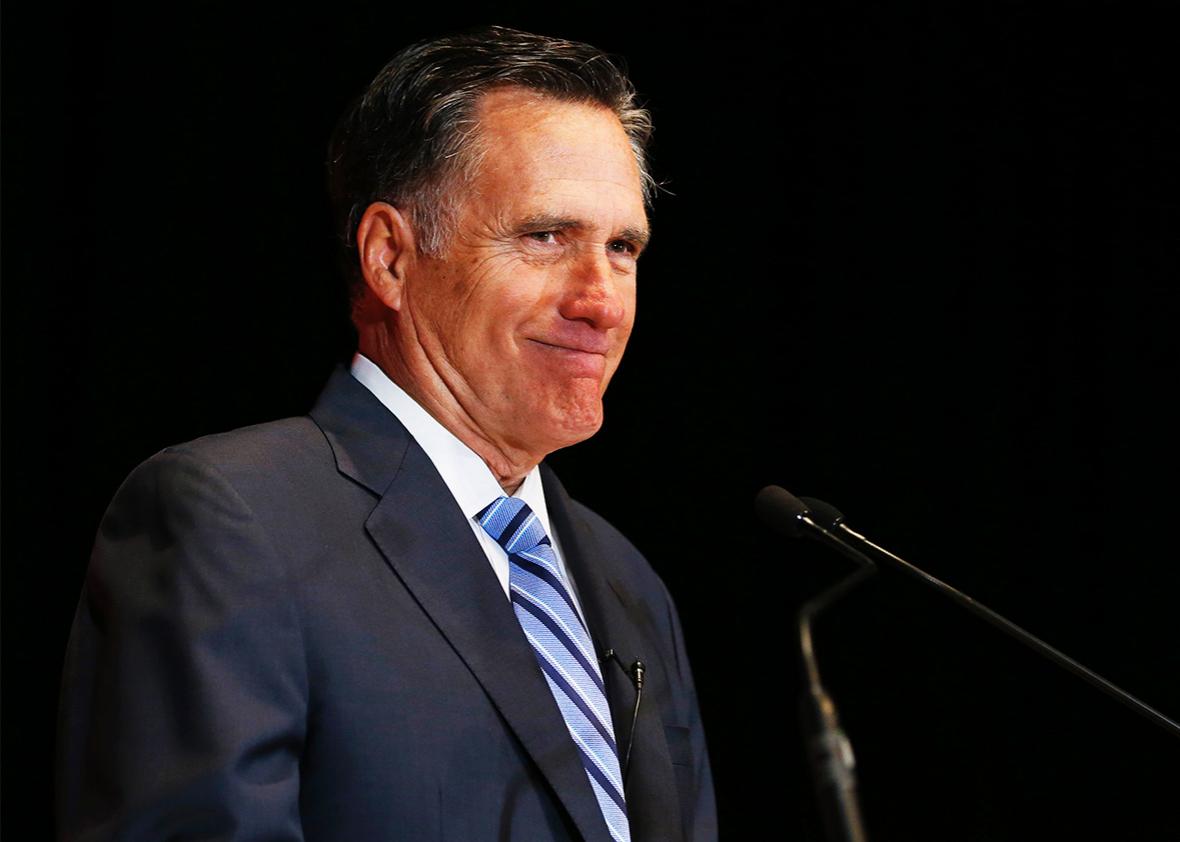

I am increasingly convinced that Mitt Romney, Trump’s most scathing Republican critic, is the man for that particular job. Romney is known for his risk aversion, and it is admittedly difficult to imagine the GOP’s 2012 standard-bearer launching an independent campaign. Running as a third-party candidate would be expensive, and to say that Romney would be an underdog would be an understatement. Romney has already exposed himself and his family to intense scrutiny and the exhausting grind of a presidential campaign on two occasions, so his loved ones would surely question his sanity. By standing against Trump, he would invite a level of vitriol that would make his last bid for the presidency look like a breeze. Nevertheless, Romney should run. And if he were to run as himself—a pragmatic problem solver with a long record of success in business and in government—there is a chance, albeit a slim one, that he might actually succeed.

There are a huge number of voters who are desperate for a different candidate. A recent NBC/Wall Street Journal survey reported that two-thirds of registered voters can’t see themselves supporting Trump while 56 percent feel the same way about Hillary Clinton. Among Republicans, 43 percent hold a negative opinion of Trump, and a quarter believe that a Trump victory would “mostly bring the wrong kind of change.” In a Trump versus Clinton race, anti-Trump conservatives might be tempted to find a hard-right candidate to serve as their champion, but they’d be wise to find someone who could plausibly attract centrist voters and who would have some meaningful base of support. Romney fits the bill perfectly.

Romney’s experience as a corporate turnaround artist was used against him in 2012, but it would surely help him in a race against Trump. Indeed, Romney could argue that he is the only candidate who understands what it would take to rebuild America’s industrial base and to punish China for turning a blind eye to intellectual property theft. During his 2012 campaign, Romney was cautious in making the case for economic nationalism, partly because it was anathema to many elite conservatives. In the season of Trump, Romney would be free to make this case more vigorously.

Then there is Romney’s potential appeal to devoutly religious voters. The GOP primaries have illustrated an underappreciated divide: Though Trump has fared well among voters who don’t go to church regularly, he has won relatively little support among those who do. It could be that more observant Christians see Trump’s professions of faith as insincere in light of the colorful life he’s led and that they recoil from his arrogance and chauvinism. Regardless of why these voters have rejected Trump so far, Romney’s squeaky-clean image may prove more appealing in a three-way race. Many believed that Romney’s Mormon faith would alienate evangelical Christians in 2012, but exit polls found that he actually won 79 percent of the evangelical vote. It is also easy to imagine Romney winning states in the mountain West and the Great Plains, which have thus far proven resistant to Trump’s charms.

Why would Romney be a stronger third-party candidate than, say, Michael Bloomberg? As a self-made billionaire entrepreneur, Bloomberg is everything Donald Trump pretends to be, and his presence in the race would have done much to deflate Trump’s claims to greatness. The trouble is that Bloomberg would be unacceptable to conservatives. Though Bloomberg sees himself as a no-nonsense centrist, his faith in technocratic fixes—such as his effort to regulate away plus-sized sugary soft drinks—and his views on social issues place him firmly on the center-left. The former New York City mayor ultimately concluded, correctly, that if he were to run for president against Trump and Clinton, he’d likely help elect Trump, as his views on immigration and gun control are all but identical to those of the presumptive Democratic nominee.

Given the central role immigration has played in this election, a third-party candidate would do well to stake out a position distinct from that of the GOP and the Democratic Party. In Miami this week, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders said they would not deport unauthorized immigrants with clean criminal records. Essentially, they seem to be suggesting that there is no need for immigrants to go through the proper legal channels, provided they are nonviolent. It is not difficult to imagine such a policy setting off a migration wave that would match those seen in Germany, Sweden, and other European democracies over the past year and that has contributed to a sharp increase in anti-immigration sentiment in those countries. Trump, in contrast, has called for mass deportation of unauthorized immigrants currently residing in the U.S.

The vast majority of Americans would favor a position between these two extremes. Here is where Romney could step in. Though Romney was staunchly opposed to amnesty for unauthorized immigrants, his approach was less draconian than Trump’s. Romney was quick to remind voters that he favored sensible reforms that would make life easier for legal immigrants while also cracking down on those who enter the country unlawfully. This is a stance that would be broadly acceptable to right-of-center voters, but it might also appeal to some Democrats.

If you don’t think Romney has it in him to break ranks with the GOP, consider that he made a point of breaking with party orthodoxy when he ran for a U.S. Senate seat in 1994. In a debate with Ted Kennedy, Romney noted that he had been an independent in the Reagan-Bush years and that he was “not trying to return to Reagan-Bush.”

In his 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns, Romney often seemed to be fighting his own instincts to fit the demands of Republican primary voters. As a third-party candidate, he would have a much freer hand. He could try taking a page from his father, George Romney, who ran for governor of Michigan as a centrist reformer, a race he won by a comfortable margin. The elder Romney devoted his time in office to bettering the lives of Michigan’s poorest citizens, including the children and grandchildren of black migrants from the Deep South. During his short-lived 1968 presidential campaign, he promised to spark an economic revival in the inner cities, rural communities, and American Indian reservations that had been left behind by the postwar boom. If Mitt channeled George’s inclusive spirit in 2016, he could offer a way forward for the post-Trump right. Just as the death of the Whig Party led to the rise of Abraham Lincoln’s Republicans, an independent Romney campaign could pave the way for a new center-right party free of the GOP’s baggage.

There is one final reason Romney could prove to be an impressive third-party candidate. Trump has profited enormously from free media coverage in the GOP primaries. But in a general election, he will be facing a well-funded Democratic opponent. Though Trump insists he has the ability to fund his own campaign, there is a great deal of evidence to suggest his net worth is not nearly as awe-inspiring as he claims. Some Republican megadonors are making peace with the idea of Trump as the party’s nominee. Others, however, see him as a profoundly dangerous figure. One could imagine at least some conservative donors defecting from the GOP and supporting Romney, particularly if they believe he has a shot at pulling off an upset.

Do I believe that Mitt Romney will run for president yet again? No, I do not. But I believe he should. He would be a formidable candidate if he chose to join the campaign, and he would give anti-Trump conservatives a reason to fight this fall.