GREENVILLE, S.C.—“When you come to South Carolina, it’s a blood sport. Politics is a blood sport.”

South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley was speaking with reporters Thursday morning alongside her new presidential endorsee, Sen. Marco Rubio, about whether the campaign in her state had gotten too nasty. “I wear heels,” she continued, “it’s not for a fashion statement. It’s because you’ve got to be prepared to kick at any time.”

This is presumably a line she’s delivered 10 million times. But it earned its share of chortles from the assembled national press corps in Anderson, South Carolina, just outside Greenville in the state’s conservative northwest corner. Behind every media story about dirty tricks in South Carolina politics is a not-so-secret wish: Please, please get nasty and dirty and immoral. Bury this presidential contest in filth, as you always do, you beautifully disgusting people. There’s the natural instinct to portray any middling criticism lobbied at a candidate as “classic South Carolina,” just because it fits into a pre-set narrative about wily Southern tricksters.

But has anything been unusually depraved this time around? Nothing has come anywhere near the go-to example of the whisper campaign that buried an insurgent Sen. John McCain here in 2000. Or the (unsuccessful) rumormongering effort against Haley herself in 2010. There’s still another week to go before the Democrats vote in South Carolina, but so far, the Hillary Clinton campaign has not been shopping around photos of Sen. Bernie Sanders in a turban. You know, the really nasty stuff that no one can condone … but secretly hopes for anyway.

Not that the candidates have been engaged in a lovefest. The crossfire is rapid and consistent. But mostly it comes in the form of pathetic whining about mailers or websites or advertisements that, while stupid, aren’t anything unusual.

Rubio met with the press Thursday morning for a couple of reasons. The first was to show off Haley, whose endorsement he hopes can catapult him above Sen. Ted Cruz for second place Saturday. (Rep. Trey Gowdy and Sen. Tim Scott, the other members of Rubio’s potent South Carolina endorsement troika, milled about in a corner while the press engaged Rubio and Haley.) Another reason was to whine about Cruz’s latest unconscionable deed: a Cruz-backed website—“The Real Rubio Record”—that used a photoshopped image of “Marco Rubio” and “Barack Obama” yukkin’ it up and shaking hands after consummating the “Rubio-Obama Trade Pact,” for which Rubio allegedly provided the clinching vote. Most sinisterly, Rubio—a right-hander—is shaking the left-handed Obama with his left hand, a sign of deferential weakness and conspiracy.

Rubio was so upset about this image that he had his adviser, Todd Harris, show it off to the press following an early rally at a CrossFit in Greenville. “This is how phony and how deceitful the Cruz campaign has become,” Harris said, in pure disbelief that the Cruz campaign would dare imply that Obama and Rubio have shaken hands.

“It’s not real. The picture’s fake, it’s a photoshop of someone else shaking hands—and it appears it isn’t Barack Obama either,” Rubio said in Anderson. “So I think now this is a disturbing pattern, guys. It’s a disturbing pattern. Everyday they’re making things up—in this case they literally made up a picture.”

Literally made up a picture. To illustrate a point on a website. Rubio then pivoted to the much more substantial point that Cruz, himself, flip-flopped on granting Obama Trade Promotion Authority—aka the “Rubio-Obama Trade Pact.” (There’s a substantial amount of hatred for globalization among the rank-and-file in this part of upstate South Carolina, even though it’s home to a massive, job-creating BMW facility that seems to span half of the I-85 corridor between Greenville and Spartanburg.)

“They literally made up a picture,” Rubio reiterated.

Rubio almost solely complains about how dirty Cruz is. His base doesn’t overlap much with Donald Trump’s, and the two leave each other alone. Cruz’s base, however, overlaps with both Trump’s and Rubio’s, and so he has to fight a two-front war. Not that he doesn’t enjoy the challenge.

Much like Rubio is aghast at how Cruz’s malevolent campaign would use a photo illustration on a website, Cruz is stunned at how nastily the campaigns of both Trump and Rubio have turned on him.

“Marco Rubio is behaving like Donald Trump with a smile,” Cruz said Wednesday morning in Seneca, near Clemson. The main purpose of his event was to mock a cease-and-desist letter that “Donald’s lawyer” had sent Cruz’s campaign to block the airing of a very non-defamatory political ad. But Cruz devoted the second half to bundling Rubio with Trump.

“At the debate, I made three points about Marco’s record on immigration,” Cruz went on. “And Marco’s response was exactly the same as Donald’s: It was to yell, ‘liar, liar, liar.’ ” Cruz likes to mention that he, despite their many disagreements, has never impugned the personal character of a fellow senator. This itself is untrue.

Another issue that the two have been bickering about is push polls, also known as “calls.” Both Trump and Rubio have accused Cruz of push polls that, again, just level the usual criticisms that Cruz always makes in plain daylight about Rubio and Trump. Cruz has denied having anything to do with them, which may be true in the narrowest legal sense. Cruz insists that the real candidate commissioning the ghastly push polls is Rubio, whose push polls falsely attribute nasty push polls to Cruz.

“And yet Marco, his campaign, sent out 500,000 robocalls with a major campaign surrogate of his accusing our campaign of being behind the push polls,” Cruz said. “He was asked today what evidence he had for that. He had no evidence. He had no basis whatsoever.” Cruz said he understood that the Rubio campaign is disappointed, but campaigns have to be about “ethics,” and passing along talking points via telephone calls is simply a bridge too far.

Ads that show old clips? Websites with illustrations? Robocalls? None of this stuff is what we expect of South Carolina. Where are the illegitimate minority children, the tawdry affairs—the fabricated, humiliating, and typically prejudiced rumors that campaign personnel distribute to shady, pseudonymous “fixers” with the instructions: Our fingerprints can’t be on this. Understood?

The nastiest player in the South Carolina primary so far has been Pope Francis. Declaring that Trump isn’t a Christian, ahead of a Southern Republican primary? Now we’re getting somewhere. If Pope Francis could expand this into an allegation that Trump has Muslim children out of wedlock who recently joined ISIS, then we’d be rolling.

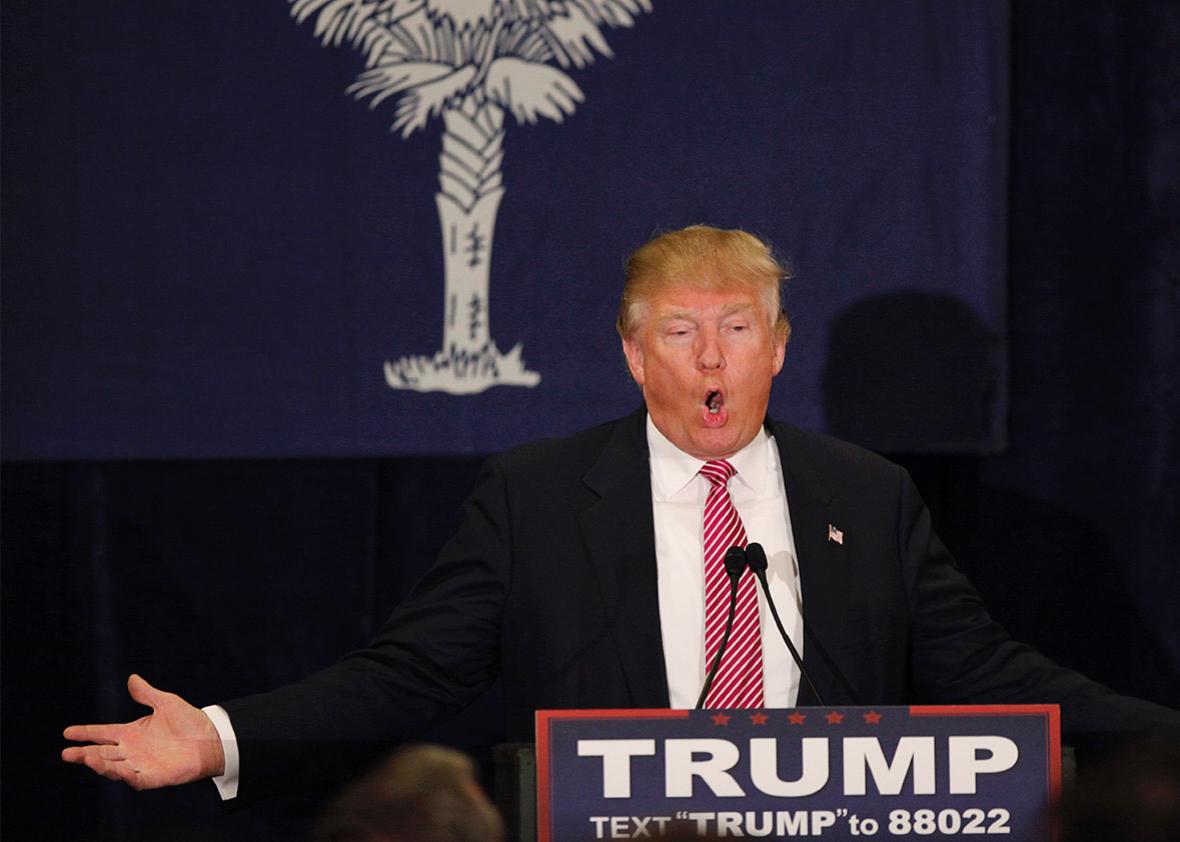

Trump did not mention the pope’s comments during his Thursday afternoon rally at Gaffney’s Broad River Electric Cooperative. (“Do we love electricity?” Trump said upon taking the stage. “How about life without electricity? Not so good, right? Not so good.”) Perhaps it was just too late in the day to get into it with a pontiff. Had he chosen to, though, he may have found a receptive audience.

“I don’t have a lot of use for the pope,” said Diane Cannady, a Trump supporter from Fort Mill. “To me, he’s just another man.”

Thurman Davis, from Blacksburg, supports Trump because, “in my opinion, he’s the only one who loves America. This is my country and I want my kids to have a good future.” He added that “in my opinion—don’t get me wrong—I lived in Florida and I went to school with a very large Mexican population. And I love the people. But I don’t think we should roll the red carpet out for them and let them be as I am.” He supports the wall. When asked about the pope’s comments—that people who think in terms of building walls are not real Christians—Davis turned around to display the embroidery on the back of his jacket. It read: “JESUS FOREVER.”

Trump himself has an interesting relationship with “nastiness.” It’s a quality he seems to despise in his competitors but thrusts forth as a central reason for his own candidacy. At one point during his speech, Trump openly accepted the mantle of nastiness. “We’ve got to be nasty, folks,” he said, mocking the pundits who thought he came across as too “nasty” in the last debate. “Can I be nasty? Oh, we’re gonna be so nasty. ISIS is not going to like us anymore. ISIS is going to be not so happy, folks.”

When it came to the other candidates, though, Trump used “nasty” in its more traditional, negatively connoted form.

He disparaged “this guy Jeb Bush—who’s got zero chance, by the way, zero chance of winning” as a “nasty guy, you know, in his own way, he’s a nasty guy” for spending so much money on negative ads in New Hampshire. “And they’re not even correct,” he continued. “At least get them correct.” He briefly second-guessed himself: “Although maybe I’m better off if they’re not correct, my polls go up every time he plays the ad, so I don’t know.”

Extended spiels about Cruz’s dishonesty have become as regular a part of Trump’s speeches as the appetizer course of poll readings and the scattered asides about how pathetic Bush is. Cruz “lies, he lies badly,” Trump said to cheers. “You know, he holds up his Bible and then he lies—let me tell ya, that guy lies. He is a liar.” Trump insisted that he “doesn’t say that easily—and I know the difference between having fun and playing the game, and, ya know, we’re in politics—but I know the difference between that and lying.” He mocked Cruz’s voice saying, Donald Trump doesn’t like the Second Amendment. “I’m the strongest person on the Second Amendment—like, by far!”

None of this—either Trump’s labeling of Cruz as a “liar,” or Cruz saying that Trump is soft on the Second Amendment and other issues, like abortion—would fall into the category of “dirty tricks” or a “Southern mud fight” or whatever other fantastical terms are thrown about around the South Carolina primary. It’s just the normal sort of back-and-forth that happens in the closing stage of a primary. The large field ensures that the volleys are more frequent, but the projectiles themselves couldn’t be smaller. It’s not nasty, and it’s not dirty. It’s just puerile white noise.