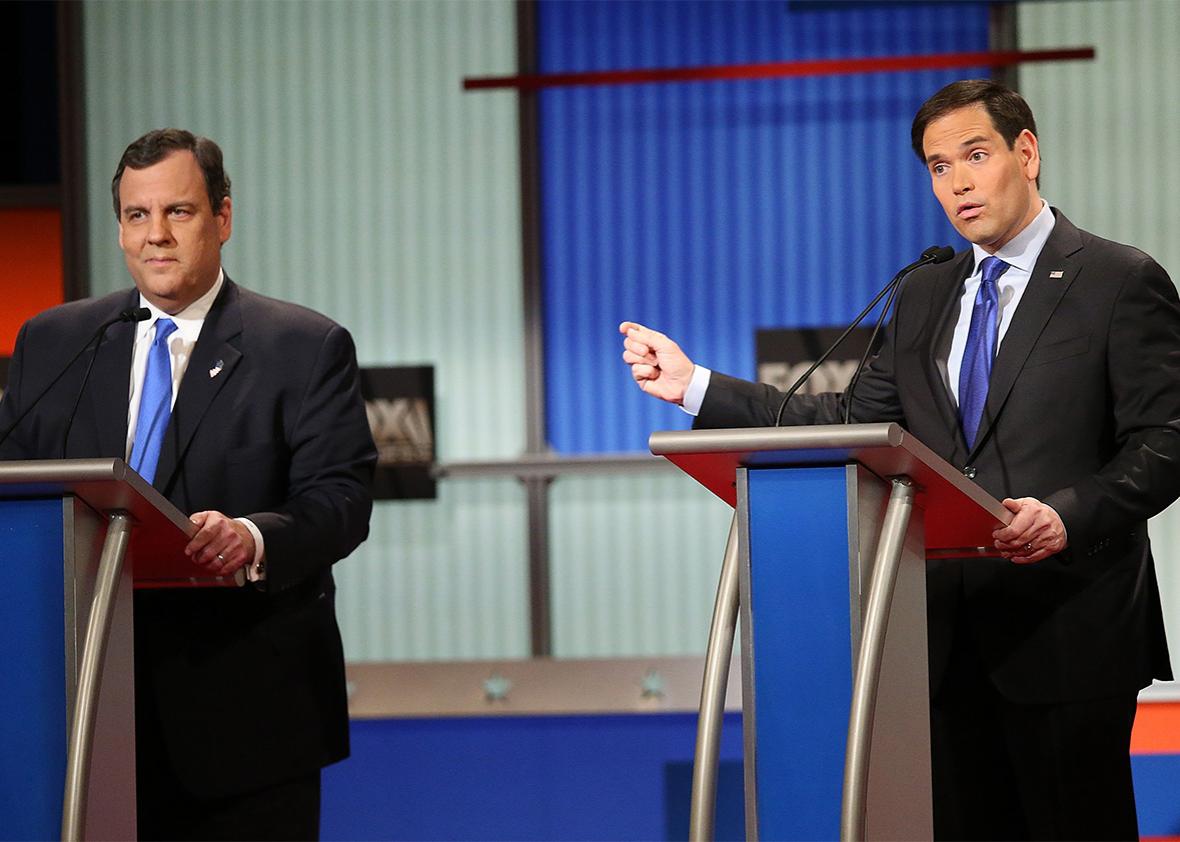

Gov. Chris Christie, in his only significant contribution to the 2016 presidential race, thumped Sen. Marco Rubio in New Hampshire and significantly complicated his supposed glide path to the nomination. I personally consider this hilarious, but others disagree. There may well be a sense among Rubio well-wishers that Christie, having allegedly blown the 2012 election for Mitt Romney with his embrace of President Obama, has now blown the 2016 election by taking out the party’s most electable candidate.

Conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer has called Christie’s debate thrashing of Rubio a “suicide attack” that boxed Rubio out of New Hampshire. Indeed, the proper political term is “murder-suicide,” and Christie pulled it off magnificently. Give the man some credit—this was a feat. He took down Rubio, went nowhere himself, safeguarded Trump’s lead, and allowed Gov. John Kasich, whose campaign doesn’t seem structured to exist much longer, to take the coveted second-place finish. Was Christie a secret Democratic operative sent to complete an intricate sabotage mission? We’ve heard stranger.

To say that Rubio is now finished! would be as foolish as saying he had the nomination in his back pocket following a third-place finish in Iowa. Rubio’s admission Tuesday night that the loss was his fault—that he had a poor debate, and that it will never happen again—was an attempt to cordon off the defeat as an isolated event. Now that Christie is out of the race, it is true that a New Jersey governor will never demolish him in a debate again.

But Rubio and his supporters who may despise Christie, or blame him for blowing the party’s best hope for November, should treat what happened as a growing experience. Winning presidential nominations is not easy, and paths to the nomination rarely fall into one’s lap.

That it looked after Iowa that the nomination would fall into Rubio’s lap should have been a telltale sign that the forces of cosmic balance were about to screw him. Sen. Ted Cruz’s Iowa win didn’t seem to be translating into a noticeable bounce; perhaps he was, despite his more ample resources, just another factional Iowa winner like Rick Santorum or Mike Huckabee who couldn’t navigate his way to a majority. The theory that Donald Trump wouldn’t be able to convert his polling support into hard votes also seemed to be playing out after Iowa. Meanwhile, late voters in Iowa broke for Rubio, and New Hampshire appeared to be following suit. Each were signs that “the rules” were reasserting themselves, and that the broadly acceptable candidate with the most endorsements from party officials would begin to ascend as voters got “serious.”

So much for that. The only part of this sunny theory that still holds up is that voters—at least the ones who would consider voting for someone like Rubio—are getting serious. And their serious determination is that Rubio needs a lot of work. If you can’t handle one week with everyone punching at you, how are you going to handle, say, a general election?

Christie helpfully reminded Rubio that he cannot dawdle around with third-place finishes and expect the party to naturally funnel his way in mid-March. He cannot begin ignoring his Republican rivals and training his eye on the general election yet. He still has to fend off Jeb Bush and Kasich on one side and Cruz on the other. He has to take more questions. He has to de-robotify his presentation, or at least tweak his internal programming to present a more relatable exterior to the humans he seeks to court. He has to expect that he will lose rather than win.

One reason not to write off Rubio is that he has taken a pounding like this before and lived to tell about it. He was written off following his work on comprehensive immigration reform. Though it may not have been the most noble move to back away from the bill he co-authored, doing so allowed him to repair his relationship with conservatives to the point that he now enjoys strong favorability ratings and room to grow. If he could come back from that drawn-out episode, he can come back from this poor showing. But no one’s going to hand him anything.

Read more Slate coverage of the GOP primary.