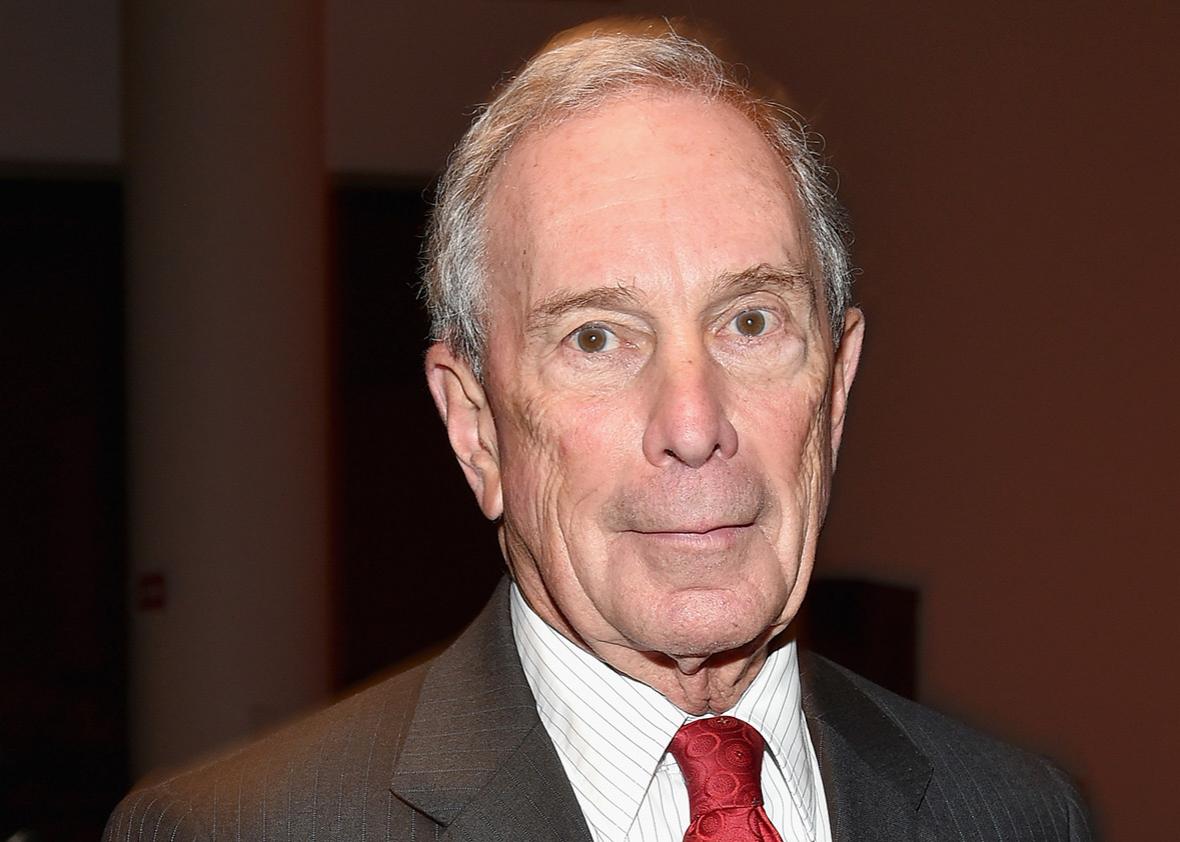

By now, the Michael Bloomberg presidential trial balloon is a ritual. At some point in a presidential election—usually on the eve of voting—someone will run a story on the former New York mayor’s presidential ambitions. National reporters, who are either based in New York or Washington, will debate it, and we’ll eventually conclude that the exercise is a bit silly. Bloomberg won’t run—it was just a trial balloon, after all—and we’ll move on.

On Saturday, the New York Times reported on Bloomberg’s newest presidential speculation:

Mr. Bloomberg, 73, has already taken concrete steps toward a possible campaign, and has indicated to friends and allies that he would be willing to spend at least $1 billion of his fortune on it, according to people briefed on his deliberations who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss his plans. He has set a deadline for making a final decision in early March, the latest point at which advisers believe Mr. Bloomberg could enter the race and still qualify to appear as an independent candidate on the ballot in all 50 states.

Bloomberg’s conditions for entering the fray are simple: If Republicans nominate Sen. Ted Cruz or Donald Trump, or if Democrats are on the verge of choosing Sen. Bernie Sanders over Hillary Clinton, he enters the race. If not—if Hillary Clinton or an “establishment” Republican win their respective primaries—he stays out. “If Hillary wins the nomination, Hillary is mainstream enough that Mike would have no chance, and Mike’s not going to go on a suicide mission,” explained former Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell.

On the other hand, there are hints in the Times story that Bloomberg would enter the race against Clinton too, if she moved left in response to Sanders.

One obvious observation to all of this is that Bloomberg’s gambit might backfire: If there’s anything that could generate more enthusiasm for Bernie Sanders (or even Donald Trump), it’s the threat of an independent run from the living avatar of America’s billionaire class.

With that said, I think there’s more to the latest Bloomberg trial balloon than just amusement at its recurrence. Bloomberg’s conditions for entering the race—in short, Clinton must lose—reveals something important about the Democratic Party coalition and tells us the likely outcome of a Bloomberg candidacy: If Bloomberg runs, then the Republican, even if it’s Trump, wins.

First, on the Democratic coalition. For as much as pundits and observers describe the Democratic Party as “liberal,” that overstates the case. Yes, the party sits on the left side of the American political system, but Democratic voters aren’t a liberal monolith. Just 41 percent of self-identified Democrats claim the label. Thirty-five percent say they are “moderate,” and 21 percent say they are “conservative.” The number of liberal Democrats is growing, but it’s not a majority. Not yet, at least.

Who are those Democratic moderates and conservatives? Some of them are black American and Latino voters who don’t hold conventionally liberal beliefs but support the Democratic Party for a variety of other reasons. And some of them are the shrinking class of working-class white Democrats. But some are the suburban whites who help make or break Democrats in national elections in states like Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. They are college-educated and middle-class, or even affluent. They hold liberal views on issues like same-sex marriage, reproductive health, climate change, and gun control, and support core Democratic programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid (although they’re reluctant to raise taxes to fund new programs).

But they differ with the most liberal Democrats over issues of race and racial inequality. They’re less likely to back affirmative action programs or to see racial discrimination in policing or housing as a pressing problem. It’s difficult to quantify this group, but it’s likely they are part of the 22 percent of Democrats and 45 percent of white college-educated Americans who—according to the Public Religious Research Institute’s American Values Survey—believe that minorities have the same opportunities as whites. Not only do they reject explicit racial politics, but they tend to push back against Democrats who are too closely identified to minority interests. It’s part of why Bill Clinton made a pivot away from black voters in the 1992 election and why Sen. Barack Obama downplayed the extent to which he was the black candidate in the 2008 one.

In 2016, against a Republican like Trump or Cruz, they will probably side with the Democratic candidate, whether it’s Clinton or Sanders. But Bloomberg complicates things. He governed New York as a business-friendly, socially liberal mayor, interested in gun control, public health, and public safety. And while he reached out to minority communities—winning 50 percent of black New Yorkers in his 2005 mayoral re-election race—he also resisted pressure from minority communities to end programs like “stop and frisk.” His final election victory reflected this: Bloomberg won 67 percent of whites, including 59 percent of white Democrats and 70 percent of white independents. Blacks, on the other hand, supported his opponent 76 percent to 23 percent, and Latinos rejected him 55 percent to 43 percent.

In a race between a Democrat who, because of the demands of party politics, is sensitive to minority groups and a Republican who rejects social liberalism and a role for the state at all, Bloomberg offers a third way: A centrist or even conservative spin on Democratic policies without the racial politics of the Democratic Party. And while Bloomberg wouldn’t win a three-way race, he could draw enough of those suburban white Democrats to give the popular vote to a Republican opponent. Which is what the polling shows. Against Sanders and Trump, Bloomberg draws 12 percent support and makes the race a coin toss. Against Clinton and Trump, he draws 13 percent and gives the popular vote to Trump.

That Bloomberg could give the White House to a candidate he clearly loathes, in either scenario, is the reason we shouldn’t take his trial balloon too seriously. Still, all of this illustrates the degree to which the Democratic coalition is broad but fragile, and that under the right conditions, it could easily fracture.