When Sen. Bernie Sanders entered the fray, few thought he would make a sustained and serious challenge to Hillary Clinton. But in the months since he launched his campaign he has exceeded expectations, winning liberal Democrats and charging toward victory in New Hampshire, and approaching it in Iowa.

Now facing a truly competitive race, Team Clinton has reached for the sword, swinging against Sanders on everything from health care and gun control to his age and his electability, warning Democrats that his “democratic socialism” could cost them the election. On guns, they’ve landed blows, and they hope to do the same on his ability to win. On health care, by contrast, they’ve missed, frustrating liberal commentators and bringing new donations to Sanders’ campaign.

But the rapid rise of Sanders—and the pointed attacks from Clinton—obscure the extent to which the overall state of the race hasn’t changed. Clinton is still the favorite for the nomination, even as her path gets a little rockier and a little more difficult. And the reason isn’t hard to understand.

Take the recent Monmouth University poll of the Democratic race. Between December and January, Clinton lost her lead with white Democrats. Indeed, it vanished, dropping 23 points. Now, she’s tied with Sanders, 43 percent to 43 percent. But she’s grown her lead with black and Latino Democrats, winning 71 percent to 21 percent for the Vermont senator, up from 61 percent in January.

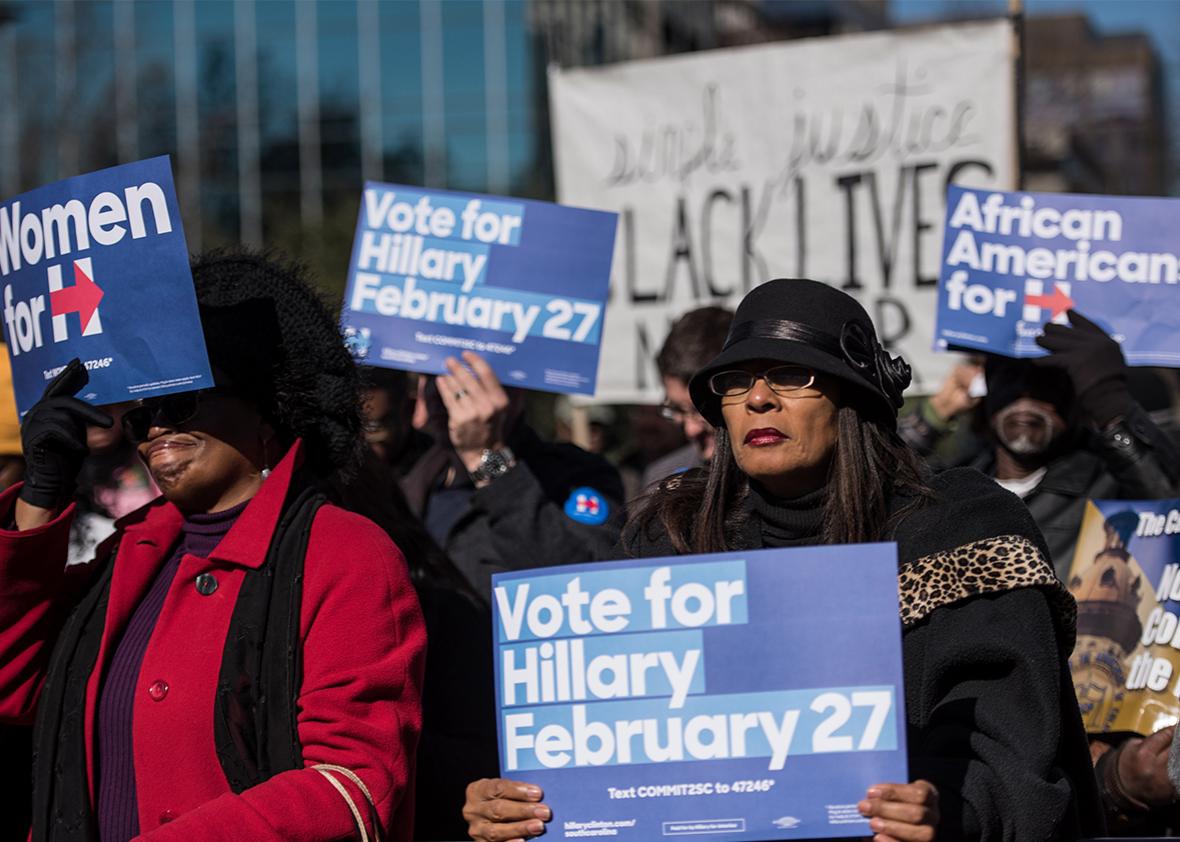

This lead with black and Latino Democrats isn’t just responsible for Clinton’s margin in national polling—where she outpaces Sanders by an average of 13 points—it’s responsible for her massive lead in the South Carolina primary, where black voters predominate and where Clinton crushes Sanders with an average margin of 40 points (although there’s been little polling in the state since the new year).

Which gets to a broader, more important point. Minority voters—and black Americans in particular—are the firewall for Clinton’s candidacy and the Democratic establishment writ large. As long as Clinton holds her lead with black Democrats, she’s tough (if not impossible) to beat in delegate-rich states like New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Ohio, and Texas. Even with momentum from wins in Iowa and New Hampshire, it’s hard to see how Sanders overcomes Clinton’s massive advantage with this part of the party’s electorate . That’s not to say he won’t excel as an insurgent candidate, but that—barring a seismic shift among black Democrats, as well as Latinos—his coalition won’t overcome her coalition.

This, in itself, raises a question. Why are black Americans loyal to Hillary Clinton? What has she, or her husband, done to earn support from black voters? After all, this is the era of Clinton critique, especially on questions of racial and economic justice. The Crime Bill of 1994 supercharged mass incarceration; the great economic boom of the 1990s didn’t reach millions of poor and working-class black men; and welfare reform couldn’t protect poor women in the recession that followed. And the lax regulation of the Clinton years helped fill a financial bubble that tanked the global economy and destroyed black wealth.

At the same time, it is important to view the relationship between black voters and the Clintons in the context of the times when it was forged. During the Republican presidencies of the 1980s, black voters felt alienated and ignored by mainstream politics. Even Democrats seemed to keep their distance, a sense that helped fuel Jesse Jackson’s bids for the Democratic nomination in 1984 and 1988.

From the beginning of his campaign, Bill Clinton did the opposite. Neither he nor his wife took blacks for granted, assiduously campaigning for the black vote in every possible venue. He emphasized his childhood in the segregated South and pledged to appoint blacks to high-ranking positions. In an approach that Barack Obama would mimic 16 years later, Clinton focused his efforts on black civic and community organizations, from church networks to civil rights groups. It paid off. Black voters carried Clinton through the Southern primaries and gave him the margins he needed to win the nomination.

To a large degree, Clinton’s black outreach—premised on his background and his cultural familiarity—was symbolic. Put frankly, Clinton felt comfortable around black people and never tried to hide it. On the other hand, however, he never promised to directly address black interests and he—after winning the nomination—tried to distance himself from black activists (e.g. the “Sistah Souljah moment”). But symbolic politics is potent, and black voters stuck with Clinton through the general election.

This established a pattern, of sorts. Clinton would always rely on black voters as a base, cultivating their support and appealing to them throughout his presidency. When it suited the circumstances, however, he would distance himself. He wasn’t a fair-weather friend, but he wasn’t a reliable ally either. But what was true was the extent to which he treated black Americans as equal partners in national life. He addressed black concerns in national addresses like the State of the Union and worked with black leaders on priorities like the Crime Bill. Both Clintons made active efforts to appeal to and respect black voters, which was not the norm for American politics (although, with George W. Bush’s “compassionate conservativism,” it became the norm, at least for a moment).

All of this left a lasting impression. Black voters didn’t always agree with Clinton, but they liked and—to an extent—trusted him. When Hillary ran for Senate, she took a similar approach, working hard to build ties to New York state’s—and New York City’s—black community. And this outreach informed Bill Clinton’s (highly symbolic) decision to base his post-presidency in Harlem.

For more than 20 years, Bill and Hillary Clinton have engaged with black voters, black leaders, and black communities. They’re familiar. And when coupled with the role blacks play in the Democratic primary—stalwart voters who tend to support the safest choice—this adds up to a powerful advantage for Hillary. So much so that the only candidate to breach it—Barack Obama—had to run an almost flawless campaign, in addition to being black himself. Had Obama failed to build ties to the black political establishment—and had he failed to show his viability with wins among white Democrats—it’s not clear he would have overcome and reversed Clinton’s advantage with blacks.

In the eight years since that fight, Hillary Clinton has worked to mend her rifts with black leaders and black voters. She joined the Obama administration and served with enthusiasm, she—and Bill—continued their retail outreach, speaking to black voters in black spaces. There’s still work to do—the 2008 primary was ugly—but the Clintons are doing it.

With expansive policies for economic equality, Sanders might have real appeal for black Americans. But it takes more than good policies to forge a political connection. It takes hard, dedicated work. And to overcome a decades-long relationship between black voters and the Clintons, it will take harder work still.

This truth gets to a broader fact about where we are in the Democratic presidential primary. Clinton is a transactional politician who operates from the center of the Democratic Party. Sanders is an ideological politician who has worked, for his entire career, to push the Democratic Party to the left.

Clinton is struggling to build enthusiasm for her campaign because it’s hard to build excitement over a transaction. She can promise to fight for Democrats, she can promise to represent them, but she can’t bring a “political revolution.” But Sanders, as a possible nominee for the presidency, has the opposite problem. It is hard to transition from protesting the party establishment to trying to lead it. Whether he can do so—whether, in effect, he can become more transactional—will play a big part in his electoral success. If he can break or subvert Clinton’s relationship with black Democrats, he can win. If he can’t, he won’t.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the Democratic primary.