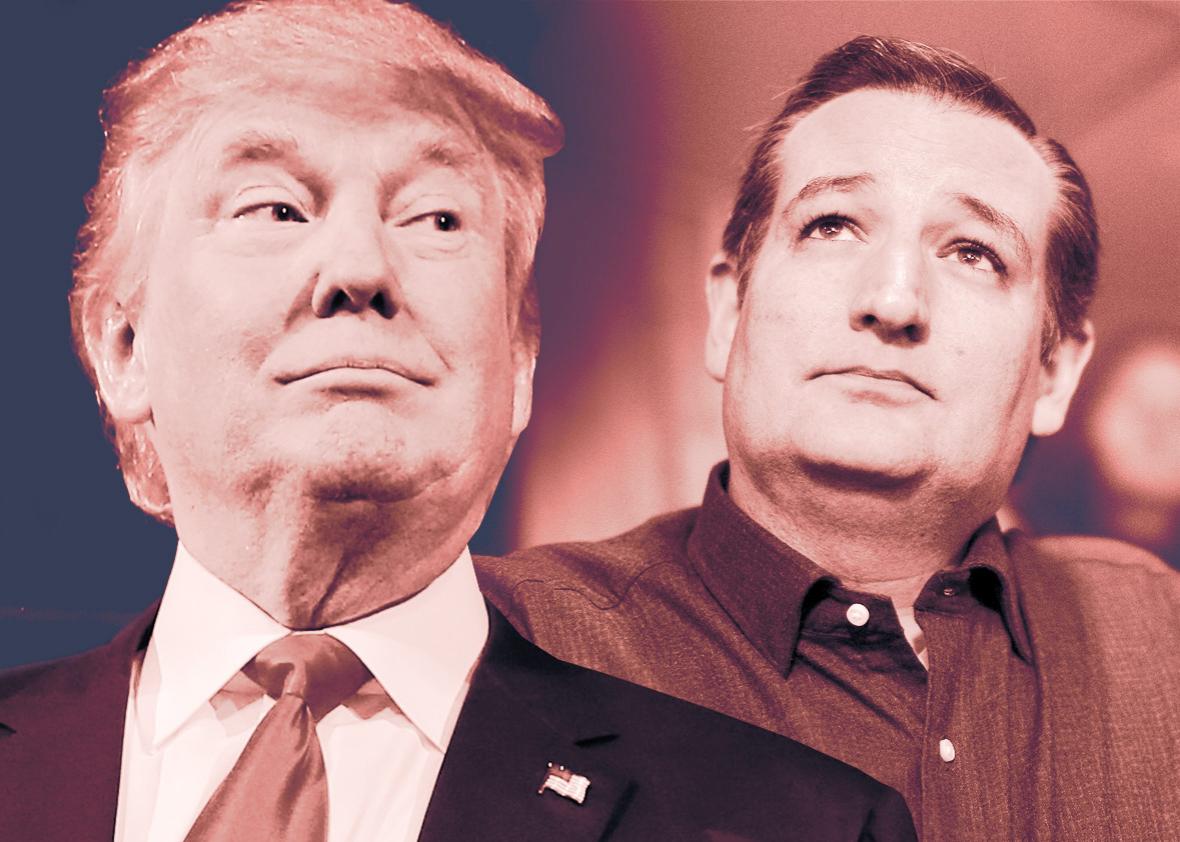

Donald Trump is a nativist demogogue who attacks racial and religious minorities and heaps praise on authoritarian leaders abroad. He borrows from white nationalists and channels the worst impulses in American life. He’s an opportunist with little connection to the Republican Party or the conservative movement.

If he has a serious rival for the GOP presidential nomination, it’s Ted Cruz, the caustic senator from Texas. Cruz is a genuine ideologue, with deep support in the “counter-establishment” of conservative activists and right-wing billionaires. But he’s also been a commissar of sorts in the GOP, blasting fellow Republicans for any deviation—real or perceived—from orthodoxy and leading the party in an almost self-destructive charge against the Affordable Care Act and the Obama administration.

Trump is vulgar, but singular—he stands for no one but himself. Cruz, however, represents a faction of the GOP with real enemies in the party. And if he wins, he brings that faction to power.

Which means that in official Washington—where Cruz is a pariah—the choice is easy. “I’ve come around a little bit on Trump,” said Sen. Orrin Hatch in an interview with CNN. “I’m not so sure we’d lose if he’s our nominee because he’s appealing to people who a lot of the Republican candidates have not appealed to in the past.”

“We can live with Trump,” said one Republican lobbyist to the New York Times. “Do they all love Trump? No. But there’s a feeling that he is not going to layer over the party or install his own person. Whereas Cruz will have his own people there.”

“You can coach Donald. If he got nominated he’d be scared to death,“ explained Charles Black, a former GOP operative, to the Times. ”That’s the point he would call people in the party and say, ‘I just want to talk to you.’ ” John Feehery, a former Republican congressional aide, put it simply. “Trump won’t do long-lasting damage to the GOP coalition,” he said to the Times. “Cruz will.”

As professional Republican pundits, operatives, and lawmakers, these figures care about the health of the party and their place in it. They want to win, and they want to preserve their influence. Trump appears malleable. Win or lose, they see themselves as safe. Cruz, on the other hand, is a threat. An unapologetic ideologue, Cruz isn’t interested in outreach to the other side. Instead, he believes he can win by generating a wave of conservative enthusiasm. If Americans tend to punish naked extremism at the ballot box, then Cruz could cost the GOP the White House in a close election. And worse, as Feehery suggests, he could damage the party in Senate and congressional races. But beyond winning or losing, an ascendant Cruz brings a new class of conservative activists to Washington, who might displace the present establishment. In that sense, Cruz is an existential threat.

But the mood is different among conservative intellectuals. For them, Trump—who escews conservatism in favor of an aggressive ethno-nationalism—is the existential threat. It’s why, on Thursday, National Review published a symposium titled “Against Trump,” where a cross-section of conservative writers and personalities made the case against the Donald for a conservative audience. Whether or not it’s effective—how many Trump supporters read and heed National Review?—it’s an important signal from another set of party elites.

At the same time, it’s a flawed one. To defeat an enemy, you have to understand him, and it’s not clear that any of the writers in National Review’s symposium understand Trump or the forces in their party and movement that sustain him. More than anything, they attacked him for his ideology, or lack thereof. “Trump is no conservative—he’s simply playing one in the primaries,” wrote Mona Charen. “[V]irtually every Republican presenting himself to voters swears so-help-me-God that he is a conservative,” wrote Brent Bozell, “Many of these politicians are calculating, cynical charlatans. … Trump might be the greatest charlatan of them all.”

Under all of this is the assumption that Republican voters are conservatives first, driven by conservative principles. And to an extent, that’s true. But it’s self-serving to ignore, or deny, the extent to which Republican voters have been mobilized and organized by the politics of white backlash, and the degree to which conservative organs like National Review have been active participants in the process. The classic example is William F. Buckley’s infamous 1957 editorial, “Why the South Must Prevail,” where the National Review founder and premier conservative intellectual made the case against the civil rights movement. “The central question that emerges,” writes Buckley, “is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas in which it does not predominate numerically. The sobering answer is Yes—the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race.”

White backlash politics informed Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign (where he lifted George Wallace’s rhetoric, wholesale), Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign (where he called the Voting Rights Act “humiliating to the South”), and George H.W. Bush’s 1988 bid for the presidency (see: “Willie Horton”). In recent years, they’ve fueled the career of former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, herself elevated to the national stage by prominent conservative intellectuals. Indeed, from affect to appeal, Palin is an important antecedent to Trump.

Which gets to the irony of this apparent divide in the Republican Party elite, between those who might back Trump and those who disdain him. Conservative intellectuals—in terminal denial over the role of race in their movement—can’t see how Trump flows naturally from undercurrents and strategies in conservative politics and conservative rhetoric. The white backlash to liberal identity politics helped build the modern Republican Party, and now—in its most virulent form—it is consuming its host.

Republican officeholders and operatives, by contrast, are far more clear-eyed. As crafters and practitioners, they see Trump as a malleable force, using rhetoric that isn’t too far from their own. If harnessing an aggressive white backlash is what it takes to win, so be it. And if Trump proves too alienating, then they can disavow him. Or at least, that’s what they hope.

Here, National Review is right. If Republicans embrace Trump, there’s no going back. His brand of nativist politics will ascend in the GOP and transform conservatism from a movement of principles (that has harnessed resentment) to one of just resentment, all in the face of a diverse and broadly tolerant public. Like some alien symbiote, Republicans will shape Trump for just a brief time before Trumpism—as a political force—has the last word.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the GOP primary.