If pundits and observers are skeptical that Donald Trump can win a primary—much less the primary—it’s not because they don’t buy his popularity. That much is evident. He still leads national polling, he’s still ahead in early states like New Hampshire, and his supporters are well in his corner: 63 percent of Trump backers say their minds are “made up” about their candidate of choice.

They’re skeptical because it’s not enough to be popular. You also need the organizational strength to bring your backers to the polls. You need to convert your polling lead into tangible performance, and for a candidate like Trump—who pulls from groups that don’t often vote in primaries—that takes extra time, extra effort, and extra money. And despite his (alleged) wealth, Trump has been unwilling to spend the money it takes to actualize his popularity and make it more than just a number in a polling average. At most, he’s prepared to run ads. But ads don’t move bodies. Staffers, volunteers, and field operations do. To that point, in the 2012 general election—a different beast, but still instructive—the effect of ads disappeared after a short period. The effects of a good ground game, however, didn’t. “Other things equal,” writes political scientist John Sides, “Obama’s vote share was about three-tenths of a point higher in counties where Obama had one field office and six-tenths of a point higher in counties where Obama had two or more field offices.”

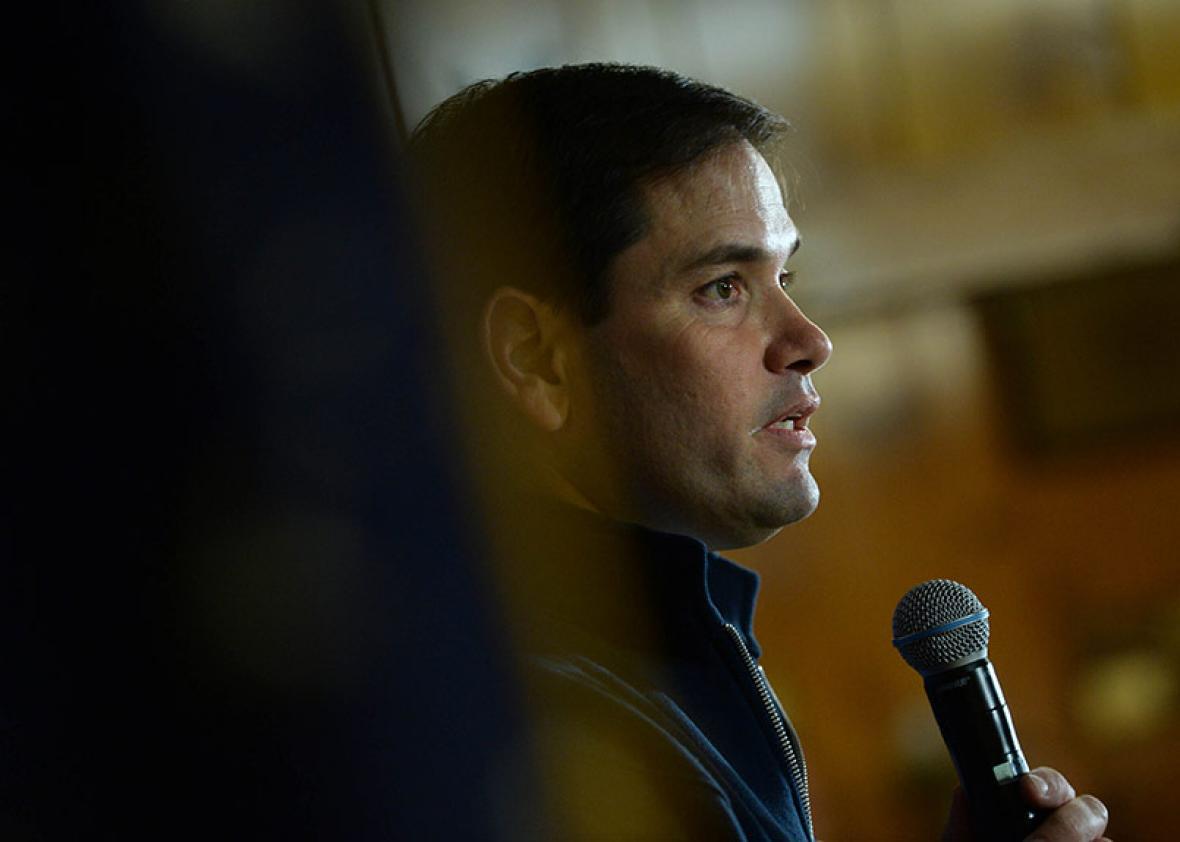

So, if you want to discount Trump in actual voting, there’s your rationale. And Trump’s not alone. As we move closer to February 2016, when voting begins, there’s another candidate who has an auspicious gap between his popularity and his presence in the field—Florida Sen. Marco Rubio.

Unlike Trump, Rubio is a serious player, the favorite of Republican elites and important donors. In the fight for the establishment lane of the GOP primary, he easily surpasses Jeb Bush, Gov. John Kasich, and Gov. Chris Christie. And for many pundits, he’s the natural choice for the nomination: a young conservative with orthodox views and strong communication skills who could pull Latino voters to the party. If Rubio didn’t exist, you’d have to build him in a lab, a Universal Politician designed to win national elections.

Even in the present Republican atmosphere of bombastic outsiders and counter-establishment candidates, Rubio could win. Or at least, he has the raw material to win. But to an extent that’s strikingly similar to Trump, he isn’t focused on winning.

To be sure, Rubio has run ads in early states like Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada. He has volunteers, fundraisers, and a campaign apparatus. He gives speeches and attends events. But unlike Bush and Christie—who have focused on New Hampshire—or Ted Cruz—who has camped out in Iowa and South Carolina—Rubio has spread his time and dollars around. “Rubio,” notes the Associated Press, “has tried to avoid prioritizing any one of the early voting states, by running a nationally focused campaign that leans on strong debate performances and television advertising.”

Rubio believes he can energize supporters and win elections on the strength of his televised communication skills. It’s why, for instance, he’s spent little time in either Iowa or New Hampshire, opting instead for national public appearances that reach households in both states. In a real sense, he’s running the same type of campaign as Trump, where you aim for a national profile and not the allegiance of a given state.

If Rubio were close behind Trump, this approach might make sense. But he’s not—he trails Trump. Which is to say that this isn’t the campaign of someone who wants to be presdient as much as it’s the campaign of someone who likes to run for president.

The simple truth is that you can’t win a nomination with air power. It’s helpful to win debates and blanket the airwaves with ads, but it won’t bring victory. What Rubio needs if he wants to win is a strategy for mobilization that brings his voters to the polls and persuades undecided Republicans. But there’s no sign he has one, or even wants one. “One of the biggest mistakes you can make in a presidential primary like this is to mistake action for progress,” said a Rubio strategist to the Washington Post in October. “The days of having to have 50 field staffers and 25 offices are done.” One argument is that this is a reasonable strategy in a crowded field of candidates. Instead of committing yourself in hopes of winning one state, you hold onto second or third in several states. As long as you don’t underperform, you’re viable, and if you outperform, you’re golden. And instead of fighting for a win in the early game, you grind it out in the late stages.

But again, this depends on either a structure that can deliver votes, or tremendous hustle from the candidate (hustle which, from Rubio, is still forthcoming). Absent that, you risk defeat by better-organized opponents. Well-organized candidates can take advantage of rules to build powerful leads (Obama throughout the 2008 primaries), and supremely driven ones can surge ahead with previously uncommitted supporters (Rick Santorum in the 2012 Iowa caucus). Likewise, you shouldn’t discount the power and importance of winning early. Early wins give a burst of publicity and prominence that skilled candidates can turn into fundraising, volunteers, and eventually votes.

Rubio’s main hope, if he doesn’t win an early state, is that he survives and the actual winners are too brittle and factional to capitalize on their good fortune. In which case, he can pull ahead in later contests, even if he’s against Cruz, who has built a formidable ground game in Iowa, South Carolina, and much of the South, which votes early. It’s the path sketched by conservative activist Erick Erickson, who argues Rubio can win as long as he treads water in New Hampshire. If Republican voters are willing to wait out the process, then he can recover delegates in the more moderate North and Midwest, where candidates like Cruz are weaker.

But even this depends on incredible good luck: Not only does Trump have to collapse, but his voters have to split evenly through the field. Given their profile and Cruz’s courting, however, I wouldn’t hold my breath.

The big point is this: Marco Rubio would be in much better shape if he would devote his time and energy to campaign building and infrastructure. It would boost him in early states, and sustain him through Super Tuesday. As it stands, his path to victory depends—in essence—on luck. And if anything goes worse than he expects, he’s finished.