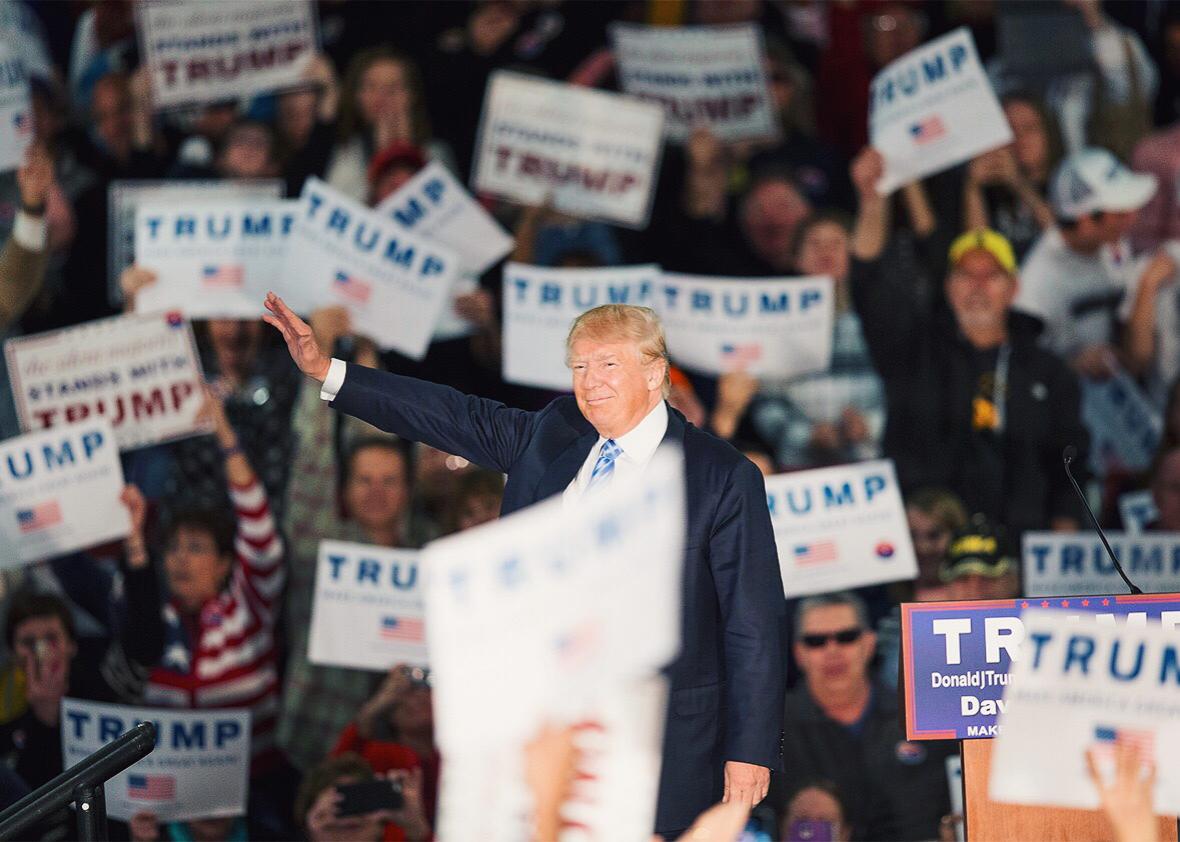

On Monday, in a press release, Donald Trump called for a “complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” It’s the latest in a series of envelope-pushing statements, which, according to pundits, were supposed to have killed off Trump’s presidential candidacy long ago. We keep thinking Trump has gone too far. And, as measured by polls, we keep being wrong.

Maybe it’s time for those of us who have predicted Trump’s demise—reporters, liberals, moderate Republicans—to face an unpleasant possibility. Trump isn’t out of touch with the electorate. We are. Trump speaks for a plurality of today’s Republicans, and many independents as well. That’s just as true on the subject of Muslims as on other topics. One of America’s two ruling parties is controlled by voters who are ready to turn the government against a religious minority.

If you don’t think this can happen in our country, you haven’t been paying attention to recent polls. In June, Gallup asked Americans, “If your party nominated a generally well-qualified person for president who happened to be Muslim, would you vote for that person?” Seventy-three percent of Democrats and 58 percent of independents said yes. Fifty-four percent of Republicans said no.

Ben Carson, a leading GOP presidential candidate, shared that view. In September, he said on national television that Americans shouldn’t “put a Muslim in charge of this nation.” Shortly after his remark, a Suffolk University/USA Today poll asked likely voters: “Would you vote for a qualified Muslim for president?” Sixty-three percent of Democrats and 54 percent of independents said they would. But Republicans, by a margin of more than 30 percentage points, said they wouldn’t.* Likely Republican voters were also closely divided on whether President Obama was a Muslim. Forty-one percent said he wasn’t. Thirty-three percent said he was.

A Rasmussen survey, also taken after Carson’s statement, asked likely voters: “Would you personally be willing to vote for a Muslim president?” Seventy-three percent of Republicans said they wouldn’t. So did 48 percent of unaffiliated voters. To smoke out respondents who were only pretending to be open-minded, the survey asked people whether most of their “family, friends and co-workers” were willing to vote for a Muslim. Only 10 percent of Republicans said yes.

During this time, from September to October, the Public Religion Research Institute broadened the investigation beyond presidential voting. To get at broader attitudes toward Muslims, PRRI asked nearly 2,700 Americans to consider a statement: “The values of Islam are at odds with American values and way of life.” Fifty-two percent of Democrats disagreed with the statement. But 57 percent of independents agreed with it. So did 76 percent of Republicans.

In a two-week frenzy beginning on Oct. 31, ISIS slaughtered more than 400 people around the world. First it killed 224 passengers on a Russian airliner. Then it blew up another 43 in Beirut. Then, on Nov. 13, it slew another 130 in Paris. After the Paris attack, U.S. pollsters asked about Muslims again. A Bloomberg survey, taken from Nov. 15 to 17, asked Americans which of two statements came closer to their views. One statement was: “Islam is an inherently violent religion, which leads its followers to violent acts.” The other statement was: “Islam is an inherently peaceful religion, but there are some who twist its teachings to justify violence.” Most Republicans chose the “inherently peaceful” version. But 32 percent (compared with 17 percent of Democrats) chose the statement that Islam was inherently violent.

In a YouGov/Economist poll conducted from Nov. 19 to 23, 71 percent of Republicans, compared with 45 percent of independents and 39 percent of Democrats, said Muslims posed at least a “somewhat serious threat” to the United States. Forty-seven percent of Republicans, compared with 28 percent of independents and 22 percent of Democrats, said Muslims posed an “immediate and serious threat.” Only 22 percent of Democrats and 30 percent of independents said they thought that the majority of Muslims worldwide supported ISIS. But 46 percent of Republicans said the majority of Muslims supported ISIS.

Would this deepening anti-Muslim sentiment create popular support for policies that explicitly targeted Muslim Americans? To answer that question, a Rasmussen survey on Nov. 17 and 18 asked likely voters: “Should most individual Muslims be monitored by the government as potential terrorists?” Only 24 percent of Democrats and 29 percent of independents said yes. But a 43 percent plurality of Republicans supported the idea.*

The hottest subject is refugees. After Paris, Republican presidential candidates Sen. Ted Cruz and Jeb Bush said the United States should favor Christians (Bush’s idea) and bar Muslims (Cruz’s idea) when screening refugees from Syria. In a four-day survey beginning on Nov. 16, ABC News and the Washington Post asked Americans whether, in accepting refugees from ISIS-affected parts of the world, the United States should give “special consideration to Christians,” or whether we should instead give “equal consideration to all people who’ve been persecuted by ISIS, regardless of their religion.” The poll question pointed out to respondents that the groups persecuted by ISIS included not just Christians but also Yazidis, “Shiite Muslims,” and “moderate Sunni Muslims.” Nevertheless, 30 percent of Republicans (compared with 15 percent of Democrats and 14 percent of independents) said the United States should favor Christians rather than treat persecuted minorities equally.

That survey overlapped with one by Fox News. The Fox poll asked registered voters about the idea of “allowing Syrian refugees who are Christian to come to the United States [while] preventing access to Muslim refugees from Syria.” The question directed respondents to choose between two statements. One statement was: “It makes sense—Christians in the Middle East have been targeted by Muslims and are not likely to be terrorists.” The other statement was: “It’s shameful—There should not be a religious test for who is welcomed into the United States.” The anti-discrimination statement was so morally loaded that I figured it would drive respondents away from the Christians-only policy. And it did: Only 10 percent of Democrats and 21 percent of independents chose the Christians-only policy. Nevertheless, 37 percent of Republicans chose that policy. Fewer than half the Republican sample chose the alternative statement against religious tests.

When you remove the moral cues about “religious tests” and “equal consideration,” Republicans lose all compunction. That’s what happened in the Nov. 19–23 YouGov/Economist poll. The survey asked: “Do you think the United States should or should not accept Syrian refugees who are Muslim?” Fifty-two percent of Democrats said we should accept the refugees. But 83 percent of Republicans, along with 62 percent of independents, said we shouldn’t.

The San Bernardino, California, attack took place on Wednesday. Over the following two days (with probably half the interviews conducted before respondents learned that the female terrorist had pledged allegiance to ISIS), a Reuters/Ipsos poll asked Americans what they thought of Muslims in the United States “following the events in Paris and San Bernardino.” Sixty percent of Democrats and 57 percent of independents chose this answer: “I view the Muslim community in the same way as any other community in the United States.” Only 30 percent of Republicans chose that answer. Forty-eight percent of Republicans chose a different statement: “I am fearful of a few groups and individuals in the Muslim community.” Twenty-one percent of Republicans chose a third statement: “I am generally fearful of the Muslim community.”

In the Reuters survey, 63 percent of Republicans, compared with 37 percent of Democrats and 47 percent of independents, agreed that “Muslims living in America have been less willing to assimilate into American society than other immigrant groups.” Sixty-three percent of Republicans also agreed that “Muslims living in America generally place religious beliefs above U.S. law.” And while 60 percent of Republicans agreed that “churches in the U.S. should be closed if authorities suspect they have ties to extremist groups or individuals,” that number jumped to 69 percent when the word mosques was substituted for churches.

Together, these polls paint a sobering picture of Trump’s party. Forty-three percent of Republicans say the government should monitor most Muslims. Fifty-four percent say they wouldn’t vote for a qualified Muslim for president, even if that candidate were nominated by the GOP. Fifty-seven percent say Islamic values are at odds with American values. More than 60 percent say not only that mosques should be closed based on suspected ties to extremists, but also that Muslims in general think they’re above the law. As for Trump’s proposal to bar Muslim refugees, it’s not even close. When the question is presented without cues, 5 of every 6 Republicans agree with him.

So let’s stop pretending the problem is Trump. The problem is the base—and by many measures, the majority—of the Republican Party. If you think we can’t elect a government in 2016 that would target a religious minority, you’re underestimating Trump. And you’re overestimating America.

*Update, Dec. 8, 2015, at 11:15 a.m.: In the Suffolk University/USA Today poll, an even greater percentage—not just more than 20 percentage points, but more than 30 percentage points—of Republicans said they wouldn’t vote for a qualified Muslim for president. (Return.)

*Update, Dec. 8, 2015, at 3:25 p.m.: Rasmussen Reports has provided data showing that in its Nov. 17–18 survey, 43 percent of Republicans supported surveillance of most Muslims, while 40 percent of Republicans opposed it. (Return.)