On Oct. 23, Hillary Clinton opened a new front against Sen. Bernie Sanders: She framed him as a sexist. Clinton took a phrase Sanders had routinely used in talking about gun violence—that “shouting” wouldn’t solve the problem—and suggested that he had aimed it at her because “when women talk, some people think we’re shouting.”

Several journalists called out Clinton for this smear. But she refuses to withdraw it. Instead, her campaign officials and supporters have escalated the attack. And now, Clinton is adding a new dimension to the controversy: race.

Some feminists applauded Clinton’s initial zinger. “Hillary Baits Bernie Beautifully,” said a headline in Salon. Melissa McEwan accused Sanders of “old-fashioned tone policing and dogwhistling about women’s shrillness.”* On Oct. 27, Stephanie Schriock, the president of Emily’s List, conceded that Sanders hadn’t singled out Clinton. But Schriock insisted that Sanders “was referring to a lot of folks who have been very adamant about [guns] and a lot of women who have been leading the fight on gun violence across the country. And I do think that is disrespectful.”

The next day, Clinton sat down for an interview in New Hampshire. Josh McElveen of WMUR asked her about Sanders: “Do you believe that he’s attacking you based solely on your gender?” Clinton replied: “When I heard him say that people should stop shouting about guns, I didn’t think I was shouting. I thought I was making a very strong case. … And I’m not going to be silenced.” McElveen followed up: “But as far as the implication that Bernie Sanders is sexist—you wouldn’t go that far?” Clinton shrugged, smiled, and sidestepped the question. “I said what I had to say about it,” she concluded.

That day, Bloomberg Politics published an article in which Sanders’ campaign manager, Jeff Weaver, joked that Clinton would “make a great vice president” for Sanders. Weaver offered to interview her for the job. As Jonathan Chait has pointed out, that’s a standard put-down among candidates: Clinton said the same thing about Barack Obama in 2008. But when Weaver tried it on Clinton, her supporters erupted. Christine Quinn, a Clinton backer, accused the Sanders campaign of sexism. Quinn pointed at Sanders himself: “I’m stunned that a man like Bernie Sanders, who has clearly committed his life to making the country a better place, would get sucked into this very dangerous rhetoric, which perpetuates sexist and misogynistic stereotypes.”

Clinton used her initial sound bite—“when women talk, some people think we’re shouting”—in at least six places. She posted it on Twitter, Facebook, and her campaign website. She also delivered it in three speeches: in Washington, D.C., and Alexandria, Virginia, on Oct. 23, and in Des Moines, Iowa, on Oct. 24. After that, I didn’t hear it, except in her interview in New Hampshire. I thought she might be done with it. But then, on Friday, she raised a new issue.

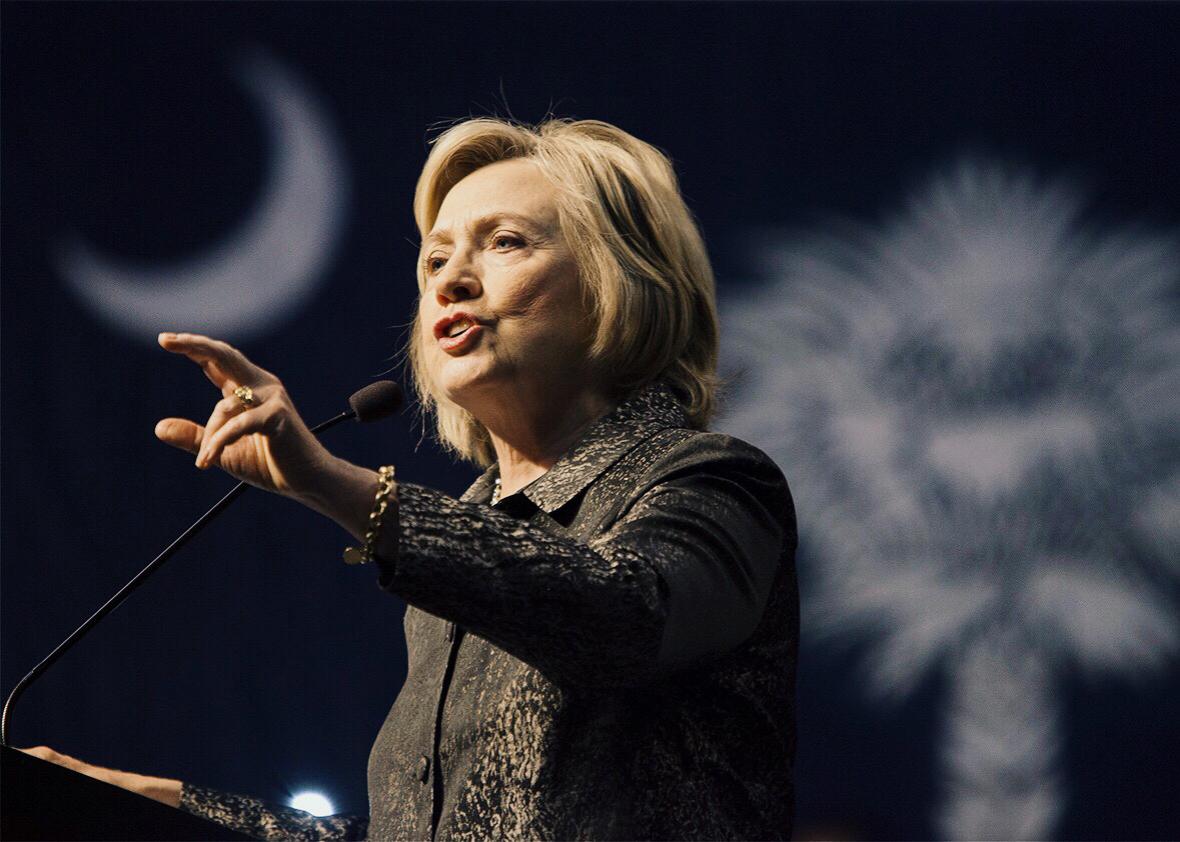

Clinton was in Charleston, South Carolina, addressing the local NAACP. She spoke against a tragic background: the massacre of nine black people in a Charleston church by a white racist. Naturally, she talked about guns. But she added a new line: “There are some who say that this [gun violence] is an urban problem. Sometimes what they mean by that is: It’s a black problem. But it’s not. It’s not black, it’s not urban. It’s a deep, profound challenge to who we are.”

The idea that urban is code for black has been around a long time. It’s often true. And it’s not necessarily derogatory: In 1920, the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes shortened its name to the National Urban League. But why would Clinton suddenly bring up, in a damning tone, people who call guns an urban problem? Who was she talking about? It can’t be the Republican presidential candidates: They haven’t disagreed enough to debate the issue at that level of granularity. The only recent forum in which guns have been discussed as an urban concern is the forum that inspired Clinton’s initial accusation of sexism: the Oct. 13 Democratic debate in Las Vegas. Pull up the transcript of that debate, search for “urban,” and you’ll see whom Clinton is talking about: Sanders.

In fact, it’s from the same moments of the debate that Clinton had already seized on. In the debate, Sanders began by saying, “As a senator from a rural state, what I can tell Secretary Clinton [is] that all the shouting in the world is not going to do what I would hope all of us want.” A couple of minutes later, Sanders told former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley: “We can raise our voices, but I come from a rural state, and the views on gun control in rural states are different than in urban states, whether we like it or not.” O’Malley insisted that the issue was “not about rural and urban.” Sanders replied: “It’s exactly about rural.” Only one other candidate used the word “urban” during the debate: former Virginia Sen. Jim Webb. A week later, on Oct. 20, Webb quit the campaign. So when Clinton, on Friday, spoke scathingly of people who call guns an “urban problem” but mean it’s a “black problem,” it’s obvious to whom she was referring.

This line of attack is rich in irony. When Clinton ran for president in 2008, she explicitly used race against Obama. She told USA Today that she should be the Democratic nominee because “I have a much broader base to build a winning coalition on.” Clinton cited an article that, in her words, showed “how Sen. Obama’s support among working, hard-working Americans, white Americans, is weakening again, and how whites in [Indiana and Pennsylvania] who had not completed college were supporting me.” A reporter asked Clinton whether this argument was racially divisive. “These are the people you have to win if you’re a Democrat,” Clinton replied dismissively. “Everybody knows that.”

Now Clinton accuses others of playing the race card. In Charleston, she told the NAACP, “Some candidates talk in coded racial language about ‘free stuff,’ about ‘takers’ and ‘losers.’ And boy, are they quick to demonize President Obama. This kind of talk has no place in our politics.”

Clinton, too, speaks in code. But in this election, her coded phrases—“some people think we’re shouting,” “some who say that this is an urban problem”—aren’t designed to veil racism. They’re designed to veil her meritless insinuations that her Democratic opponent is sexist and racist. You can argue, based on power or privilege, that playing the race card or sex card from the left isn’t as bad as playing it from the right. But even if you believe that, Clinton’s smears bring discredit on the whole idea of bigotry. If accusations of misogyny and racism are casually thrown at Sanders, voters will conclude that these terms are just rhetoric.

Seven years ago, when Clinton’s own campaign was accused of prejudice, her husband was outraged. “She did not play the race card, but they did,” Bill Clinton said of the Obama campaign. The former president went on: “This is almost like, once you accuse somebody of racism or bigotry or something, the facts become irrelevant.” Three months later, Mr. Clinton was still fuming. “They played the race card on me, and we now know from memos from the campaign and everything that they planned to do it all along,” he protested. “This was used out of context and twisted for political purposes by the Obama campaign to try to breed resentment elsewhere. … You really got to go some to try to portray me as a racist.”

Now Hillary Clinton is doing to Sanders what her husband said was done to her. She’s taking Sanders’ remarks out of context and twisting them to breed resentment. You’ve got to twist the facts pretty hard to portray Sanders as a racist or sexist. But politically, it’s easy, because once you start throwing around charges of bigotry, the facts become irrelevant. You’re just another beautiful baiter. And you won’t be silenced.

*Update, Nov. 6, 2015: McEwan asked to be named as the author who accused Sanders of “old-fashioned tone policing and dogwhistling about women’s shrillness.” Her name has been added accordingly. (Return.)