According to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 17 million Americans are “unbanked”—they are without bank accounts—while 58 million are “underbanked,” meaning they lack access to traditional banking services, from check cards to saving accounts.

Overwhelmingly, these are poor and working Americans without the steady income you need to keep an account in good order. When one month is flush and the other is fallow, it’s hard to maintain a balance, which leads to fees and other hits to your income. The FDIC found that more than 57 percent of unbanked households said they didn’t have enough money to keep an account or meet a minimum balance, while 35.6 percent of underbanked households said the same. Likewise, almost 1 in 3 unbanked households reported “high or unpredictable fees” as one reason they did not have bank accounts. Disproportionately black, Latino, and Native American, they rely on banking alternatives like payday lenders, check cashers, and pawn shops that, while predatory, are at least flexible.

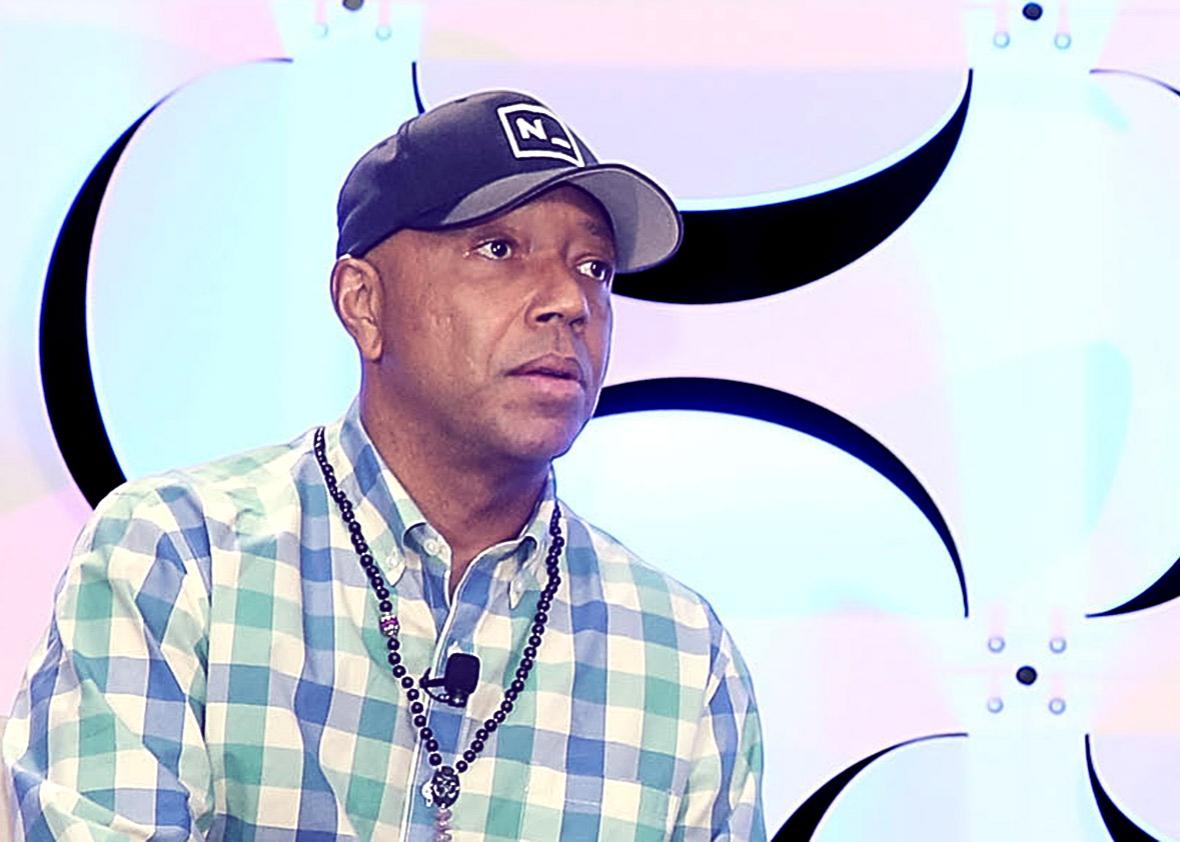

Which brings us to “RushCard,” the financial product from hip-hop and fashion mogul Russell Simmons. RushCard, according to its website, is a prepaid debit card that lets users get paychecks up to two days in advance. It takes direct deposit, and customers can add and withdraw money from ATMs. It’s meant to solve the real problems that come with being unbanked or underbanked.

In reality, however, it’s a trap. In exchange for early access to their money, users face a web of fees and charges that add up to money you must pay to use your money. On top of a monthly fee, RushCard customers pay to withdraw from ATMs, to make point-of-sale transactions, to make signature transactions, and to receive paper statements. They also pay if their account is dormant.

If RushCard were reliable, this might be a fair price for convenience. But it’s not. Beginning last week, thousands of people were locked out of their accounts following an alleged “technology transition” from the company. As Jia Tolentino notes for Jezebel, these are people with no access to cash outside of RushCard. It’s what they use to live their lives. “I’ve been a RushCard member since 2009. On October 11th I ordered a new card because my other was lost. On October 12 RushCard updated its systems and it’s been haywire ever since,” wrote one user on ConsumerAffairs.* “I have no access to my account due to whatever glitch that happen[ed] while updating system. It’s been 6 days and [the] problem [is] still not fixed. My direct deposit went in and I can’t pay my rent or bills.”

This is a disaster, largely uncovered because of whom it affects. And that’s unfortunate, as it deserves much wider attention. The RushCard fiasco illustrates the key issues of our upcoming election, from regulation of consumer financial products—politically embodied in the bitter fights over the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—to wage stagnation and unemployment that pushes poor and working Americans out of mainstream financial life, to new programs that can secure Americans against RushCard and other unscrupulous vendors.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, for example, has proposed “postal banking” as a federally sponsored alternative to payday lenders and services like RushCard. “USPS could partner with banks to make a critical difference for millions of Americans who don’t have basic banking services because there are almost no banks or bank branches in their neighborhoods,” she wrote in a Huffington Post op-ed last year. In this, Warren joins a chorus of liberal policy wonks and writers who see low-cost banking as a natural service for the Postal Service, in large part because it has done it before.

As early as 1871, writes Mehrsa Baradaran for Slate, U.S. officials have pushed a form of postal banking. During the Taft administration—following the Panic of 1907—Congress relented, and from 1911 to 1966 (when, ironically, it was abolished under Lyndon Johnson), the United States operated the Postal Savings System. “By 1934, postal banks had $1.2 billion in assets—about 10 percent of the entire commercial banking system—as small savers fled failing banks to the safety of a government-backed institution,” notes Baradaran. “Deposits also reached their peak in 1947 with almost $3.4 billion and 4 million users banking at their post offices.”

In the 1940s and ’50s—and even the ’60s—you could get away with stuffing money in a mattress and otherwise living outside of the banking system. Now, as cash becomes electronic, it’s untenable. But we don’t have to leave millions of disadvantaged people to the mercy of usurious lenders and shady operators who exist to make a profit off of people who just need easy and affordable access to funds. If we’re serious about enabling social mobility, then we have a public mission to help Americans save and use their money. And we can easily resurrect postal banking through law, or potentially, regulation.

Of course, postal banking isn’t on the 2016 radar; Bernie Sanders supports it, but outside of his interview with Fusion, that’s the extent of the discussion. But it represents a divide—regulation versus indifference, a hands-on versus a hands-off government—that defines the contest between the two parties. Which is to say that postal banking—and the victims of RushCard—deserve a spot in our national conversation.

*Correction, Oct. 20, 2015: This article originally misstated that the author had been a user of RushCard since 2009. He was quoting a RushCard user on ConsumerAffairs. (Return.)