Half an hour into Wednesday’s Republican presidential debate, Sen. Ted Cruz exploded at the CNBC moderators. “The questions that have been asked so far in this debate illustrate why the American people don’t trust the media,” Cruz fumed. “You look at the questions: ‘Donald Trump, are you a comic-book villain?’ ‘Ben Carson, can you do math?’ ‘John Kasich, will you insult two people over here?’ ‘Marco Rubio, why don’t you resign?’ ‘Jeb Bush, why have your numbers fallen?’ How about talking about the substantive issues the people care about?”

By the end of the evening, Cruz, Carson, Trump, Rubio, and several other candidates had declared war on the press. They claimed to speak for the Republican Party, the American people, and the truth. These candidates are deluded. Many of their statements were falsified on the spot. Others were exposed as absurd by their opponents. It’s true that the debate exposed a division within the country. But the division isn’t between the press and the public. It’s between people who listen to evidence—reporters, policy analysts, and many Democrats and Republicans—and an impervious, defiant wing of the GOP.

Take Cruz’s speech. It doesn’t even match the debate transcript. To begin with, nobody called Trump a villain. CNBC’s John Harwood asked Trump how he would fulfill his promises to “build a wall and make another country pay for it” (Mexico), “send 11 million people out of the country” (undocumented immigrants), and “cut taxes $10 trillion without increasing the deficit.” Second, nobody asked Carson whether he could do math. CNBC’s Becky Quick asked Carson how he would close the $1 trillion gap between current federal spending and the revenue projected from Carson’s 15 percent flat tax. Third, nobody asked Kasich to insult his colleagues. Kasich volunteered that Trump’s and Carson’s promises were impractical and incoherent. All of these questions were substantive. In fact, Cruz’s speech was a diversion from the query that had been posed to him—namely, why did he oppose this week’s agreement to raise the debt limit?

Trump had no answers to the questions about mass deportation, his $10 trillion shortfall, or the magical Mexican wall fund. He cited his own bankruptcies as a model for fixing the national debt. “I’ve used [bankruptcy] three times, maybe four times. Came out great,” said Trump. “That is what I could do for the country: We owe $19 trillion. Boy, am I good at solving debt problems.” Carson, when confronted with his own tax shortfall, suggested that his tax rate was flexible and claimed that he could make up the difference by cutting unspecified waste.

As the evening wore on, it became increasingly obvious that Trump, Carson, and their allies onstage didn’t just have a problem with the press. They had problems with fellow Republicans. Harwood brought up Ben Bernanke, the former Federal Reserve chairman who recently declared that the GOP, hijacked by the “know-nothingism of the far right,” had forfeited Bernanke’s allegiance. Sen. Rand Paul dismissed Bernanke’s criticism as “arrogance” and said it showed why the Fed should be audited. Paul, one-upping Cruz and Rubio—who had already celebrated the resignation of House Speaker John Boehner—spurned Boehner’s likely replacement, Paul Ryan, as “more of the same.”

Despite the efforts of Cruz, Carson, and Rubio to draw a wall of denial around all the candidates, reality leaked in. Kasich debunked his colleagues’ tax, budget, and deportation math. Bush backed up Harwood’s summary of a nonpartisan critique of Trump’s tax plan. When Trump insisted he could balance the budget without changing Medicare or Social Security, Bush corrected him. Two other presidential candidates who spoke during the 6 p.m. undercard debate—Sen. Lindsey Graham, who affirmed the truth of climate change, and former Gov. George Pataki, who criticized Republican foolishness about vaccines and carbon emissions—rounded out the GOP’s sanity caucus.

The main debate had its share of nonsense. Former Gov. Mike Huckabee said he would cut health care costs by curing Alzheimer’s, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. Carly Fiorina, the former Hewlett-Packard CEO, tried to blame the collapse of her company’s stock on the NASDAQ slide, even though, as Quick pointed out, HP’s stock “was a much worse performer” than the market as a whole. Bush calculated how many people had fallen into poverty since “the day that Barack Obama got elected,” thereby blaming Obama for what happened in the last two and a half months of Bush’s brother’s administration.

The candidate who attacked the media most directly and self-destructively was Trump. He accused Harwood of lying about CNBC’s original plan for a two-hour debate. Carson later joined in the accusation. But after the debate, the Washington Post’s Erik Wemple quoted an archived press release that vindicated Harwood. Trump also said the military servicemen killed by an attacker in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in July died because “they weren’t allowed on a military base to have guns.”* But the Post’s fact checkers pointed out that the servicemen had weapons, and at least one fired back. Most egregiously, Trump denied that he had called Rubio “Mark Zuckerberg’s personal senator” for promoting immigrant tech-worker visas, and he suggested that Quick had concocted the allegation. When Quick read aloud the quote from Trump’s own website, Trump shrugged it off.

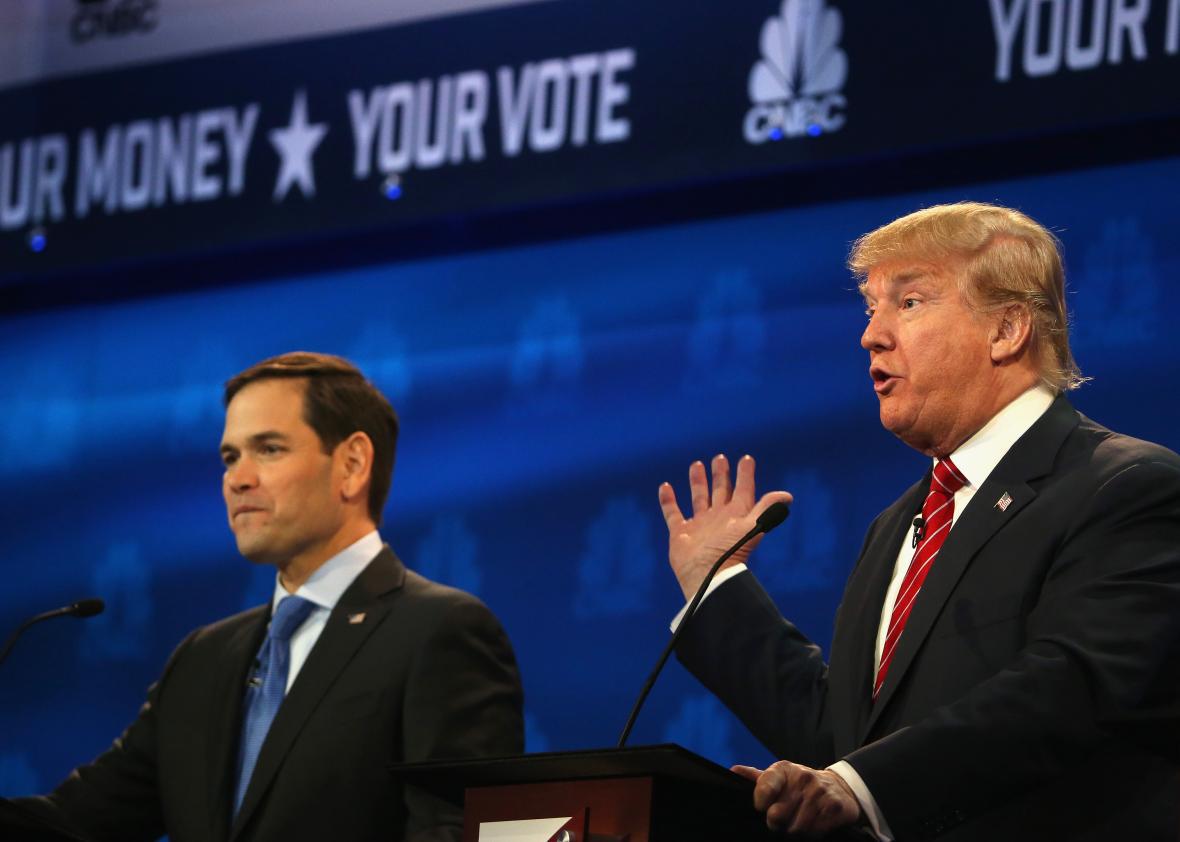

But the biggest surprise of the night wasn’t Trump. It was Rubio. Having clawed his way above Bush in the electable-candidates bracket, the Florida senator chose to stand not with the sanity caucus, but with the deniers. When Harwood quoted a nonpartisan assessment of how Rubio’s tax plan would affect after-tax income—a 28 percent increase for the top 1 percent of earners, and a 15 percent increase for the middle class—Rubio dismissed the gap, falsely, as an artifact of scale, since “5 percent of a million is a lot more than 5 percent of a thousand.” When Rubio was asked about his messy finances—a second-home foreclosure, a prematurely liquidated retirement fund, campaign money accidentally mixed with personal money—he pleaded poverty. He ignored Quick’s reminder that “you made over a million dollars on a book deal, and some of these problems came after that.”

Then Rubio went ballistic. He exclaimed: “Democrats have the ultimate super PAC. It’s called the mainstream media.” As evidence, Rubio said the press had covered up Hillary Clinton’s lies about Benghazi. “She spent over a week telling the families of those victims and the American people that [the attack] was because of a video,” said Rubio.

That’s completely false. Clinton’s first statement on Benghazi, delivered on the night of the attack, didn’t specify a motive. It spoke of people who used an anti-Muslim video to justify the attack, not to motivate it. The next day, Clinton said the victims died when “heavily armed militants assaulted the compound.” A thorough review by Factcheck.org found no evidence Clinton had blamed the video during that time.

What happened in this debate wasn’t an attack by the press on the candidates. It was an attack by the candidates on the press. Harwood, Quick, and the other CNBC panelists were no harsher to the Republicans on Wednesday than CNN’s Anderson Cooper was to Clinton and other Democrats in their debate two weeks ago. What was different this time was the reaction. Presented with facts and figures that didn’t fit their story, the leading Republican candidates accused the moderators of malice and deceit.

Arguing with the press is a constitutional right, and it’s part of a healthy society. But when the topic is economics, and when everyone is watching, you’re taking a risk. The risk is that your assertions can be checked against the historical record and the calculator. Your story can be falsified.

Yes, reporters sometimes screw up. But they have a troublesome habit of checking things. That’s what makes their statements, on the whole, more reliable than yours. It’s not true, as Stephen Colbert once joked, that reality has a liberal bias. But it is true that reality has a bias toward journalists. That’s because journalists spend a lot of time with reality. They get to know it.

Over the course of a campaign, you can learn a lot. Some of what you learn is about truth: which tax plan adds up, which promises are realistic, which view of the world most closely matches what’s being reported. But much of what you learn is about people: which candidates adjust to reality, and which don’t. In this cohort of Republicans, a bubble seems to be forming. On the outside are Kasich, Bush, Pataki, and Graham. On the inside are Trump, Carson, and Cruz. The candidates inside the bubble are doing well. Rubio is trying to join them. But bubbles don’t last.

Correction, Oct. 29, 2015: Due to production error, this article originally misspelled Tennessee.