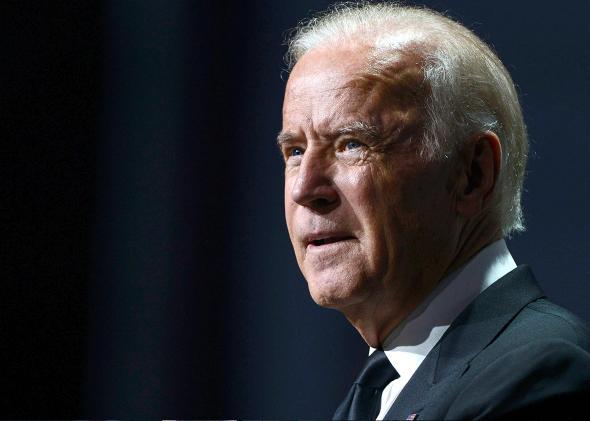

Joe Biden is expected to announce whether he is running for president any day now. If he does decide to jump in the race, there will be one critical question for which he doesn’t quite have an answer: Why are you running? Right now, there are many reasons and no reason at all: He has always wanted to run (and has run unsuccessfully twice). His son Beau, as he was dying, encouraged him to run. Hillary Clinton is not doing well, and some in the Democratic Party think he is a better general election alternative. He’s not yet ready to see the end of a long career. He connects well with middle-class voters. He has experience.

All true, but none of that really answers the big “why are you running” question—at least in the way that question has been framed so far in this Democratic contest. In all of the speculation about the vice president’s campaign, that basic question hasn’t been talked about much.

While it might seem premature to require a reason for a Biden candidacy that doesn’t yet exist, Clinton’s lack of a reason was cited again and again in early 2015 coverage of her not yet announced campaign before she entered the race in April. Sure, she had lots of advantages—the historical nature of running to be the first female president, organization, huge affection from grassroots voters—but what was her message? It continues to be Clinton’s problem, say some Democratic strategists, like David Axelrod, that she is not communicating a central rationale for her campaign. But if this is her problem, why is Joe Biden the answer? By the standard used to judge Clinton’s “why” answer, Biden would seem to be just as vulnerable.

Meanwhile, Bernie Sanders, the candidate with the energy and passion of the party base, actually has an easily discernible message—he’s running against the moneyed interests who always seem to come out on top in politics and the economy. So if the Clinton critics are looking for a candidate who can answer the “why” question quickly, that candidate is already in the race.

Still, it’s not that there aren’t arguments for a Biden candidacy. He’s experienced. He’s cautious about using military force in a time when that’s seen as wisdom rather than weakness. He’s authentic. He’s suggested that running essentially for a third Obama term would be a smart idea. But do any of these reasons immediately explain why he should run?

If he does run, he’ll quickly have to explain to Democrats his position on President Obama’s Pacific trade deal, which will get sticky very fast. He’ll also be challenged on his record on crime and police reform, an area that has become more important to his party in recent years.

One of the reasons Biden hasn’t had to face the hard “why” question the same way Clinton did is that she was only really running against herself when she got into the race. Sanders was in the race, but many of us didn’t take him seriously as a threat to a Clinton candidacy at the time. Biden, meanwhile, is being compared with an alternative: Hillary Clinton. (He has often said, “Don’t compare me to the almighty; compare me to the alternative.”) To the extent that there is support for Biden’s candidacy, it’s because right now he’s being judged against a candidate who has spent her summer on the defensive answering questions about her email.

Yet, there is one unmistakable theme at the heart of the Draft Biden movement. In an ad released on Wednesday, the Draft Joe forces play excerpts of his emotional commencement speech at Yale earlier this year in which he talks about the redemption he found after the death of his wife and daughter. It is a powerful speech and sends a historically powerful message: Biden has character. According to this argument, his life story testifies that he is made of strong stuff, and that is reason enough to trust him with the presidency.

This has been a good enough reason to elect presidents for much of American history. The people “have a right, an indisputable, unalienable, indefeasible, divine right to that most dreaded and envied kind of knowledge—I mean of the character and conduct of their rulers,” said our second president, John Adams. Character has been such an important element of presidential elections historically that a PBS series on the presidency was called Character Above All.

This idea of character has gotten muddied over the years. Democrats in the 1970s and ’80s wanted character tests because they thought it would help avoid presidents like Richard Nixon. That was the message of the Carter campaign. “I will never lie to you,” Jimmy Carter boasted on the stump. But then character came to mean the kinds of personal inquiries that undid Gary Hart in 1988, along with the attacks George H.W. Bush made against Bill Clinton in 1992 and his son George W. Bush made against Al Gore in 2000, linking him to Clinton. Democrats have since turned against using the fuzzy concept of character as a test for candidate fitness.

But if Joe Biden runs, it will be a character campaign against Hillary Clinton. That doesn’t mean there won’t be specifics discussed about wages and health care and the U.S. role overseas. But at its heart what will have gotten Biden in the race and what will animate it will be character—both his own and the perception that Clinton’s isn’t strong.

This is not an unalloyed good for Biden. The message of his Yale speech—that even under the worst circumstances, you can do good things—is powerful enough to change a person’s life when it’s heard in one context. But as a campaign ad, it flirts with appearing to exploit for political opportunity all that is sacred and powerful in Biden’s life example. A political campaign should not be a public catharsis for loss. That’s the last thing Biden would want, but such an ad or even well-meaning supporters’ use of your life story might send such a message. It’s what can happen when there’s no clear reason for why a candidate is running.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the 2016 campaign.