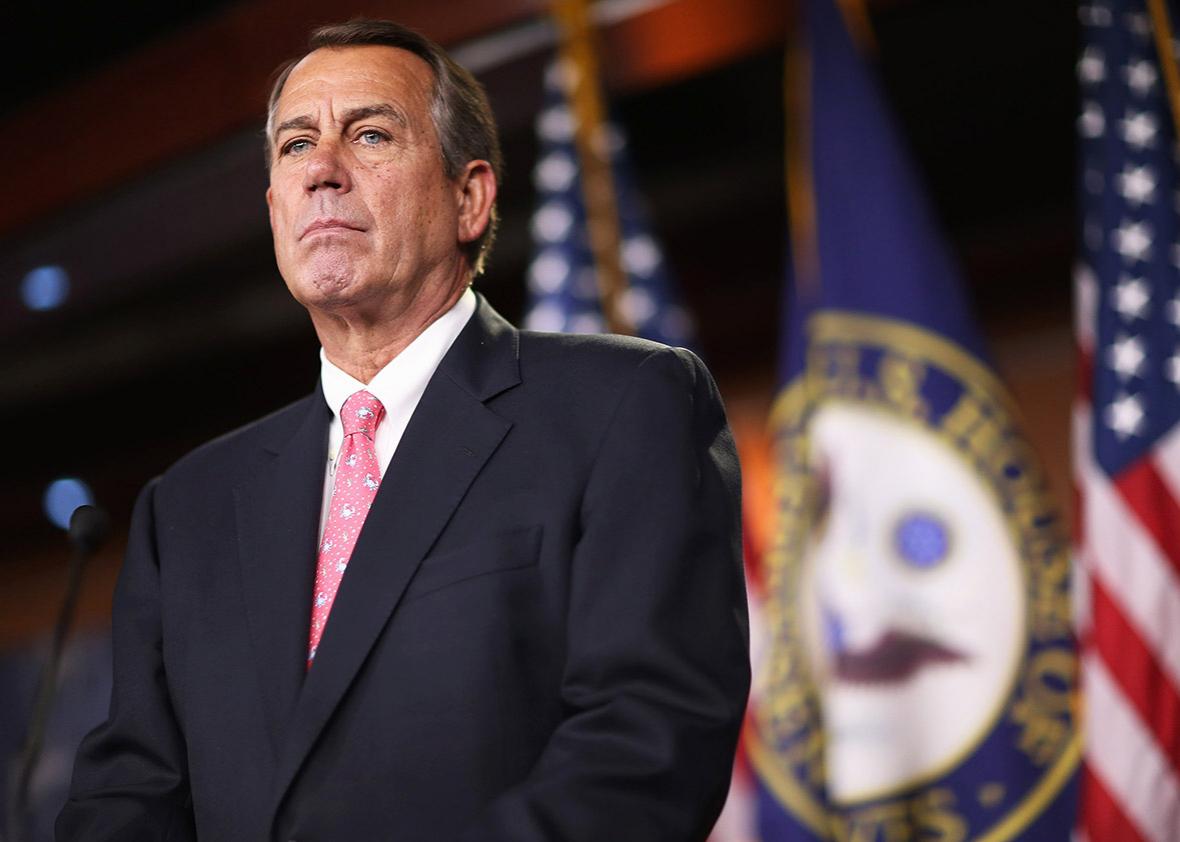

John Boehner ends his career a conservative. He helped craft the Contract With America with Newt Gingrich, and stood on the right flank of the House Republican caucus for most of his career. After Barack Obama took office, Boehner immediately moved to opposition, accusing him of “snuffing out” the America he knew and comparing politics in 2010 to America’s fight against Great Britain. “There’s a political rebellion brewing,” he said, “and I don’t think we’ve seen anything like it since 1776.” When, galvanized by this kind of rhetoric, the Tea Party wave swept conservatives into office—a second Republican Revolution—he was the obvious choice, winning a unanimous vote for speaker-designate ahead of the official election for speaker of the House. After 20 years in office, he was finally at the pinnacle of congressional power.

But then the revolution spiraled out of control. The Tea Party conservatives elected in 2010 weren’t interested in governing as much as destroying President Obama’s agenda. Everything—even routine governance—was second to the war on the president. And given his rhetoric, they expected Boehner to go along for the ride. Before 2011 the debt ceiling was an easy excuse for showmanship. Politicians would posture against raising the federal limit on debt, and after everyone was finished, Congress would raise it. Conservatives wanted to use the limit as leverage for cutting government, and they pressured Boehner into doing just that. If Obama wouldn’t slash spending, then Republicans would cap the debt, causing a default and spiking the economy into the ground.

Boehner provoked the standoff, then tried to defuse it with a long-term debt deal. But conservatives—led by then-Majority Leader Eric Cantor—wouldn’t yield, and he abandoned negotiations. If not for a last-minute bill to make automatic cuts to federal spending, the United States would have reneged on its debt, causing an economic crisis. It was an extraordinarily risky gamble that hurt the economy even as it fulfilled some Republican objectives. Still, conservatives weren’t satisfied.

Despite this, he held on. What’s striking is Boehner never supported Obama or his policies. He opposed the stimulus, voted against the Affordable Care Act, and—by all accounts and measures—was in the right wing of the Republican Party. But he was also an institutionalist; a modern-day Girondin who supported revolutionary goals but refused to plunge the United States into catastrophe for the sake of partisan or ideological goals.

For three years conservatives used deadlines as leverage, and Boehner struggled to lead Republicans to a resolution that protected his position from unruly conservatives and left the country mostly unscathed. This brinksmanship is how we got the “fiscal cliff” fight, the October 2013 shutdown over Obamacare, and the February 2015 fight over Homeland Security funding and immigration. To show his mettle to the most conservative Republicans, Boehner provoked a crisis or confrontation. And when it was clear the administration wouldn’t budge, he capitulated, telling members that he did his best.

This effort was a mixed success. Boehner survived Tea Party anger, but Cantor—who encouraged Tea Party resistance—fell to the furor, losing his seat to an obscure right-wing challenger.

What’s amazing about all of this is the degree to which Boehner and his team have actually delivered conservative policy. Under his leadership, congressional Republicans have slashed federal spending—achieving $3.2 trillion in cuts—and blocked important parts of Obama’s agenda, like comprehensive immigration reform. Despite this, rank-and-file Republicans hate him. According to a new survey from NBC News and the Wall Street Journal, 72 percent of GOP primary voters are dissatisfied with Boehner and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, including the 36 percent who want them “immediately removed” from their posts.

Spurred by controversial (and heavily criticized) videos released this summer, House conservatives want government to end funding for Planned Parenthood, despite no evidence of misconduct or criminal activity and the long-standing ban on federal funds for abortion. If Republican leaders don’t budge, then those Republicans—and their allies in the Senate—will shut down the government.

Once again, Boehner would have to fight a losing battle for the sake of defusing an intransigent minority. Once again, he’d be maligned for making a deal. But this time, he refused. Rather than indulge and debase himself for the most extreme people in his caucus, he quit. In the short term, this takes a shutdown off the table—Boehner will stay in power through the deadline for funding the government, and will likely cut a deal with Democrats to keep things going.

Beyond that, however, it’s hard to know what happens. His likely successor is current Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy. McCarthy is just as conservative as Boehner and will face the same pressures as his predecessor. Put differently, the same Tea Party revolution that elevated Boehner and Cantor eventually ended their careers. If McCarthy follows their path, and doesn’t bend to conservative demands, then the revolution might devour him, too.