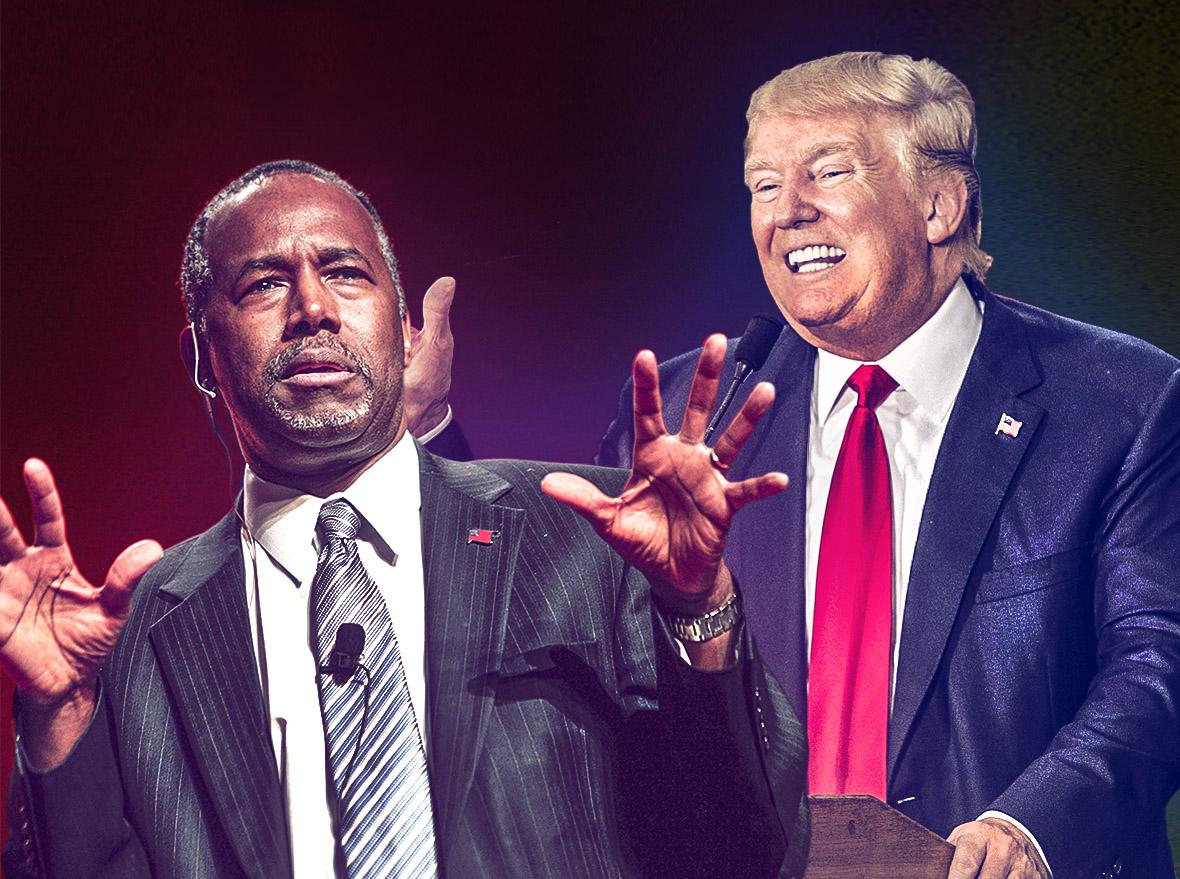

Ben Carson doesn’t want to get into a close punch and shove with Donald Trump. The two bumped into each other last week, when Carson seemed to question Trump’s faith. But before it could get out of hand, Carson apologized. That’s probably a good strategy. Every candidate who has attacked Trump—with the exception of fellow nonpolitician Carly Fiorina—has fallen in the polls. Carson, for his part, is gaining on Trump, pulling even with him in Iowa and in national polls. In the latest CBS/New York Times poll, Trump is at 27 percent and Carson is at 23 percent, up from 6 percent in August.

Carson prides himself on running a campaign that is not “bombastic or pretentious,” as he wrote in Newsmax last week. Trump, on the other hand, responded to Carson’s comments about his faith with the counterpunch that is his trademark: He went for the jugular and questioned Carson’s medical skills and faith.

These two contrasting approaches are about more than just campaign strategy. They define how each man thinks about the presidency.

On Saturday in Iowa, Trump offered a verdict on the quiet doctor: He is too nice for the presidency. “I don’t think Ben has the energy,” said Trump, who then launched into an argument in favor of being argumentative. “My tone!” Trump said in mock surprise when repeating the criticism his overheated rhetoric has garnered from rivals Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush. “They said, ‘His tone.’ T-O-N-E. And I said, you know, we need that tone today. We need energy, we need strength, and we can’t be low-key and nice and beautiful. … I don’t think it matters this time. I think we’re looking for real super competence. We’re tired with this nice stuff. We need people that are really, really smart and competent and can get things done. We need people with an aggressive tone, and we need people with tremendous energy, and I’m your candidate.”

Carson makes the case that the presidency requires having a better bedside manner. In the essay in Newsmax (written before Trump labeled him soporific), the doctor defended his reserved manner. He explained that he learned from his mother’s example that “one should never mistake soft-spokenness for weakness.” He wrote that his low-key humility came from his faith. It’s a topic he has written about and discussed before. As a young man, Carson had a volcanic temper that he cured by becoming more religious. One of his favorite Bible passages, he writes in his book Think Big, was from Proverbs 29:23: “A man’s pride brings him low, but a man of lowly spirit gains honor.”

Presumably Christian voters can recognize in Carson’s views a common faith, and they may be able to identify with the way he uses Scripture as the user’s manual for his life. But Carson’s point goes beyond personal behavior. He’s making an argument about the presidency.

I asked Carson on Face the Nation why it was important for a president to have humility. “Because you need to be able to listen,” he said. “One of the things that I have discovered throughout the many things that I have been involved in is that we have some incredibly talented people in this country. … And you have to be humble enough to be able to listen to other people and recognize that, sometimes, they might actually know more than you do and be able to integrate that. There’s nobody who knows everything. But we have an incredibly talent-filled nation … everybody seems to think that whatever they do is the greatest thing. If you’re a politician, only politicians can solve the problems. If you’re a businessman, only businessmen can solve the problems, a lawyer, doctor. That’s ridiculous. What we need to do is put our talents together, understand what our goals are, and then utilize all of our talents to accomplish them.”

Carson has also said that he is a “firm believer that one can wield power through kindness and intellect.” Carson sounds a lot like Obama did in 2008, except that while Obama had no executive decision-making experience when he ran for office, Carson has perhaps the ultimate executive experience: to cut or not to cut (and where to put the knife). Lives were literally in his hands. His patients voted on his competency with every surgery he performed.

Both Trump and Carson are nonpoliticians who have championed the power of listening. Each has argued that he will be able to make up any gap in experience by consulting experts and listening to them. Carson’s argument is that his low-key approach is the only way that can happen. In his view, Trump’s boasts and sense of himself will make him impervious to counsel.

It’s a plausible argument. History has provided us with plenty of proud characters who didn’t listen. But Trump seems to have a pretty good ear for the public mood. He is running as the antidote to politicians who have stopped listening. Voters seem to be telling pollsters that he hears them.

Of all the spats between Trump and his opponents—and the new ones we’ll see on display Wednesday night in the second debate—the one with Carson is perhaps the most interesting because it is about the office as much as it is about the men competing for it. It’s a utilitarian debate over whether humility is an impediment to action in office or a necessary requirement for a job that requires acute hearing. Or, put another way, will bravado whip government back into shape, or is it only useful in whipping up the campaign crowds? It’s a version of the age-old debate between whether nice guys finish last or whether the last will be first.