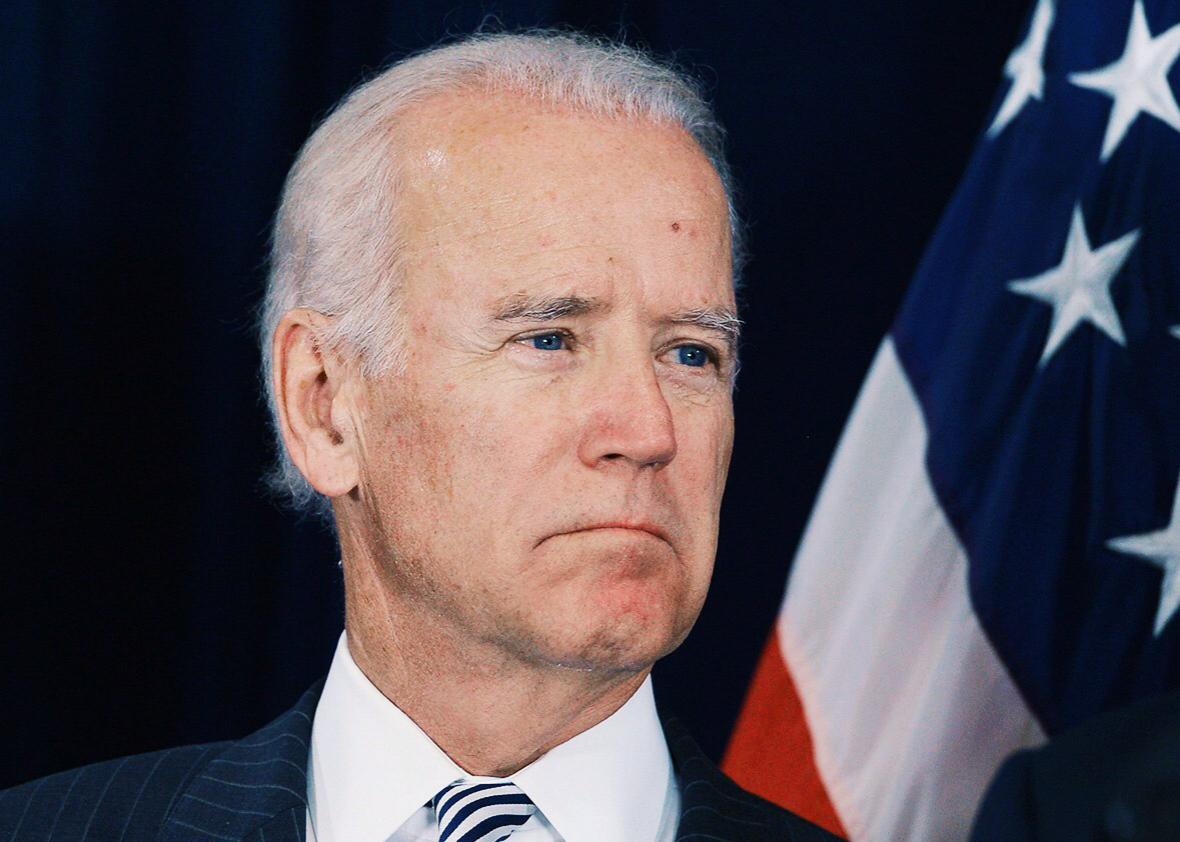

A discussion about whether Vice President Joe Biden should run for president gets deep pretty fast. Any talk about ambition, a life’s purpose, and the end of a career must take into account of all the woe Biden has had to face in his life. At age 30, a few weeks after he was elected to the Senate, his wife and 1-year-old daughter died in a car accident. Eighteen days later, he took the oath of office standing at his 3-year-old son Beau’s hospital bedside, where he was being treated for injuries sustained in the crash. In 1988 Biden had two surgeries to address the effects of cranial aneurysms with only a 50 percent chance of success. Two months ago, he buried his 46-year-old son, Beau, the victim of brain cancer. It is supposed to be the other way around. Sons are supposed to bury their fathers.

We talk about authenticity a lot in politics. Voters look for some view into the interior of a candidate where they can make a connection with something real. When Sen. Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump demonstrate authenticity, voters swarm them. Usually we have to peer pretty hard to find a true thing. With Biden, if you look too long, you might have to look away. Sen. Lindsey Graham was brought to tears recently describing Biden. During the 2008 race, I listened to a conversation picked up on a microphone of Biden talking to a voter who had also lost his wife, and I shared Graham’s reaction.

People have been calling Biden for months and telling him he should run. Normally staffers must sort these kinds of calls through a series of normal filters—sycophancy, self-dealing, dislike of the current frontrunner, and activity stirred up by reporters looking for a story. In this case, Biden and his political advisers have to engage in emotional screening: what’s emotion and what’s a genuine sign that there’s a path forward for Biden. Enthusiasm for a run may be overamplified, coming from supporters displaying the human desire to do something for a friend they see suffering. Over the weekend, New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd amplified the emotional resonance by reporting that Beau pleaded with his father to run as he was dying.*

Biden has wanted to be president for a long time. But as the deadline for his “end of summer” decision gets closer, he must come to terms with the fact that it’s not likely going to happen. Who—as a staffer, friend, or adviser—would want to throw cold water on the public talk of a candidacy before Biden makes that call himself? Why not let him enjoy the urging from the crowd? Those calls of support contain genuine respect, admiration, and gratitude. At the very least the Biden boomlet is a balm.

Despite all of the emotion, those close to Biden say that he understands the difference between the call to run and the actual brutality of the run itself. The big obstacle is that once you strip away the sentiment, Biden doesn’t have a clear rationale for replacing Hillary Clinton as the Democratic nominee. He is not of a new generation, nor does he have a particular ideological advantage. He would trade away the Democratic Party’s gender advantage in the general election. He isn’t a clean break from the Obama years, nor is he so much more identified with Obama than Clinton that he would get a bigger boost than she would if the economy starts to soar heading into November 2016.

That isn’t to say that Biden couldn’t win; it just would require the Clinton campaign’s total collapse. Absent that, Biden would have to out-campaign her. Biden’s previous campaigns don’t suggest that he is a flawless politician on the stump. He’d also have to build a financial and get-out-the vote operation to compete with Clinton’s, which would be an extraordinary organizational challenge. Clinton has a core of passionate supporters. Biden doesn’t have that—emotional affection for a person’s life story is not the same as passion for the cause of his candidacy. Clinton is also still quite popular in her own party. In the most recent Quinnipiac poll, only 9 percent of Democratic voters say they would never vote for her. Six percent said they would never vote for Biden. That’s not enough room to launch a thousand ships.

Clinton, while stumbling as she runs without any serious opposition, would almost certainly get better with a focused target she could hit. That means Biden would have to hit back. Would he really be up for that? He’d turn a campaign that started on such an emotional note into a gutter fight over Clinton’s private email server and trust issues—the kinds of subjects he’d have to exploit to win in the close combat that would be inevitable.

The Democratic presidential campaign is now going through a Biden moment. Those who have his political interests at heart will see if that flickering flame can grow into anything else as the public responds to Joe-mentum. It’s not unlike what happened with Mitt Romney earlier in the year. In the end Romney saw that the emotional outpouring that was elevating him from loser to wise man was not the same as a commitment to back another presidential run. So he settled for just being a party wise man. Now Joe Biden, who by all accounts is still emotionally raw from his son’s death, must sort through a far harder set of emotions.

*Correction, Aug. 3, 2015: This article originally misstated that Maureen Dowd reported Beau Biden pleading from his deathbed for his father to run for president. She reported that the younger Biden pleaded for the campaign as he was dying. (Return.)