Democrats being Democrats, it’s no surprise that some are skittish about Hillary Clinton’s campaign, which has been hit with scandals and weak numbers in key swing states. To these Democrats, Clinton isn’t a strong bet, and worse, there isn’t a strong alternative. Bernie Sanders? Popular, but too far to the left to unify a broad and diverse national party. Martin O’Malley? Not exciting.

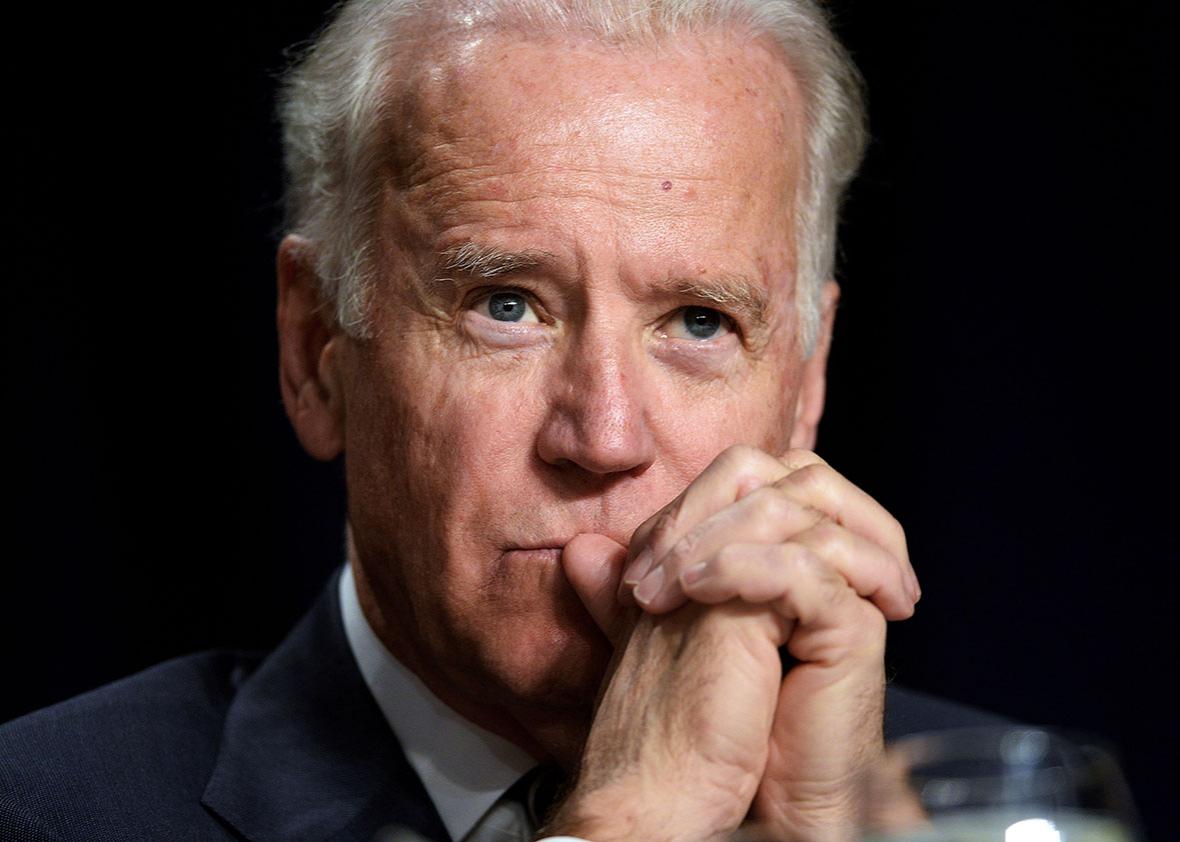

Enter Joe Biden. The sitting vice president is the third-most visible Democratic politician behind President Barack Obama and Clinton. The Wall Street Journal reports he’s moving closer to a run: He has sat with political allies, talked with family, and even met with influential Democrats like Elizabeth Warren. Yes, if he ran he’d start from behind, but he’s popular and could build a formidable primary campaign with the right backing and staff.

There’s also something to the idea of a Biden run. Even as the favorite, Clinton needs an effective sparing partner on the trail. A Biden run might be good for her skills as a candidate—a point I’ve argued before. But it’s worth stepping from the horserace to ask a different kind of question: Would a run be good for Biden? Large parts of the Democratic Party—including a confrontational activist movement—are committed to de-escalating the war on drugs and moving crime policy away from the approach of the 1980s and 1990s, an approach that Biden pioneered. This is more than trouble for his still-hypothetical campaign; it’s trouble for his legacy.

A large part of running for president is intense scrutiny on personal history and political records. But once you’re in office, that scrutiny subsides. Once you’ve left, it almost disappears. Right now, Biden is beloved, an avuncular and light-hearted figure who contrasts the president’s stoic cool and adds a touch of heart to the seemingly mechanistic Obama White House. Forgotten (at least, outside academia and a few corners of political media) is Biden’s earlier persona: a leader in America’s drug war. For a generation, Biden was at the front of a national push for tough drug laws and police militarization.

If you consider her time in Bill Clinton’s White House, that’s true for Hillary, too. The difference is that she was first lady—an advocate for her husband’s policies, but not a lawmaker. That’s why she’s able to meet face to face with members of the Black Lives Matter movement and not look disingenuous when she says she has changed her mind on the subject. Biden’s Senate career, by contrast, was defined by his aggressive and vocal support for the drug war. Here are the highlights of that history:

In 1984, he worked with Republican Sen. Strom Thurmond and the Reagan administration to craft and pass the Comprehensive Control Act, which enhanced and expanded civil asset forfeiture, and entitled local police departments to a share of captured assets. Critics say this incentivizes abuse, citing countless cases of unfair and unaccountable seizures. In one case last February, Drug Enforcement Administration officers seized $11,000 in cash from a 24-year-old college student. They didn’t find guns or drugs, but they kept the money anyway.

In 1986, Biden co-sponsored the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which created new mandatory minimum sentences for drugs, including the infamous crack-versus-cocaine sentencing disparity. A crack cocaine user with only five grams would receive five years without parole, while a powder cocaine user had to possess 500 grams before seeing the same punishment. The predictable consequence was a federal drug regime that put its toughest penalties on low-level drug sellers and the most impoverished drug users.

Biden would also play an important role in crafting the 1988 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which strengthened mandatory minimums for drug possession, enhanced penalties for people who transport drugs, and established the Office of National Drug Control Policy, whose director was christened “drug czar” by Biden.

His broadest contribution to crime policy was the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, commonly called the 1994 Crime Bill. Written by Biden and signed by President Clinton, it increased funds for police and prisons, fueling a huge expansion of the federal prison population. As journalist Radley Balko details in The Rise of The Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces, it also contributed to the rapid growth of militarized police forces that used new federal funds to purchase hundreds of thousands of pieces of military equipment, from flak jackets and automatic rifles to armored vehicles and grenade launchers.

The “crime bill” also brought a host of new federal death penalty crimes, which Biden celebrated in his defense of the bill. “Let me define the liberal wing of the Democratic Party,” he said to Sen. Orrin Hatch, “The liberal wing of the Democratic Party is now for 60 new death penalties … the liberal wing of the Democratic Party is for 100,000 cops. The liberal wing of the Democratic Party is for 125,000 new state prison cells.”

It’s true that much of this—especially the most egregious and ill-conceived measures—was a response to extraordinarily high crime rates that devastated urban communities. Many of Biden’s allies, in fact, were black Democrats from communities where violence was common and pervasive. But Biden would keep this approach, even as violent crime declined through the 1990s and into the 2000s. He would continue to vote for strong anti-drug efforts, going as far as to push for a federal crackdown on raves, citing ecstasy distribution. While Biden has shifted on some drug issues, he remains a staunch defender of his record on crime, even as Bill and Hillary Clinton have expressed their regret for the consequences of the 1994 crime bill and other anti-drug policies.

Joe Biden, in other words, is the Democratic face of the drug war. “There’s a tendency now to talk about Joe Biden as the sort of affable if inappropriate uncle, as loudmouth and silly,” says sociologist Naomi Murakawa in an interview with the Marshall Project to discuss her book The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America. “But he’s actually done really deeply disturbing, dangerous reforms that have made the criminal justice system more lethal and just bigger.” In a Democratic primary that increasingly turns on these issues, having to defend or walk back those positions is a bad place to occupy. His opponents—whether Clinton or Bernie Sanders or Martin O’Malley—will use his record against him, and millions of Democrats will begin to see him like Murakawa does: as someone who widened the path to prison for countless young men of color.

The end result for Biden would be a newly tarnished reputation and—in all likelihood—another failed presidential campaign. Which is to say that, if Biden thinks Hillary needs an opponent of her stature, he’s probably right. But before he makes the jump, he should ask himself: Is a campaign worth the damage it will do to him personally? After years in public life, is this how he wants to end his career?