Let’s look at the Bernie Sanders plan for a fairer economy. Crafted in his years as the “socialist” Independent senator from Vermont, the proposal is at the center of his surprisingly robust campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination.

If elected president (with a Democratic Congress), Sanders would end tuition for public colleges and universities, raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour, invest in new infrastructure—providing jobs and skills throughout the country—expand Social Security benefits, and make Medicare a national single-payer health insurance system. Add an ambitious plan for climate change—centered on a carbon tax—and new Wall Street regulations meant to stop another financial crisis, and you have a wide agenda for redistribution that rivals Roosevelt’s New Deal, Truman’s G.I. Bill, and Johnson’s Great Society.

You can read this as a left-liberal wishlist, but for Sanders and his supporters, it’s much more than that. To them, it is a serious plan to strike a powerful blow to inequality, from the wide gap between rich and poor, to the yawning divide between black and white. “To be honest with you,” explained Sanders in a June interview on ABC’s This Week With George Stephanopoulos, “given the disparity that we’re seeing in income and wealth in this country, it applies even more to the African-American community and to the Hispanic community.”

Partisans for the senator are even more forceful. “Closing the racial wealth gap is probably the single most effective thing that any politician could do to help advance the cause of ending structural racism in America,” writes Hamilton Nolan for Gawker, in praise and defense of Sanders. “This is because promoting progressive economic policies that work against the extreme concentration of wealth in small groups of people is something that politicians can actually do that has actual real world effects on racial inequality.”

Of course, none of this would address racism, full stop. (And despite his clumsiness with racial conversations, neither Sanders nor his campaign has ever claimed it would.) It wouldn’t end bias in hiring or other forms of employment discrimination, nor would it address concentrated poverty, residential segregation, housing affordability, or the broad problem of police violence. But in a world where the Sanders plan was law, racial minorities—and blacks in particular—would have more and greater opportunity. Couple this with his outline for reducing race discrimination in criminal justice—crafted as a direct result of protests from Black Lives Matter activists—and Sanders has built an ambitious plan for tackling racial inequality across American society.

But, for the senator’s supporters and other observers, all of this just raises a question: If Sanders is the most racially progressive candidate in the race, then why is he a target for Black Lives Matter activists, even after he addressed core concerns over police violence and criminal justice reform?

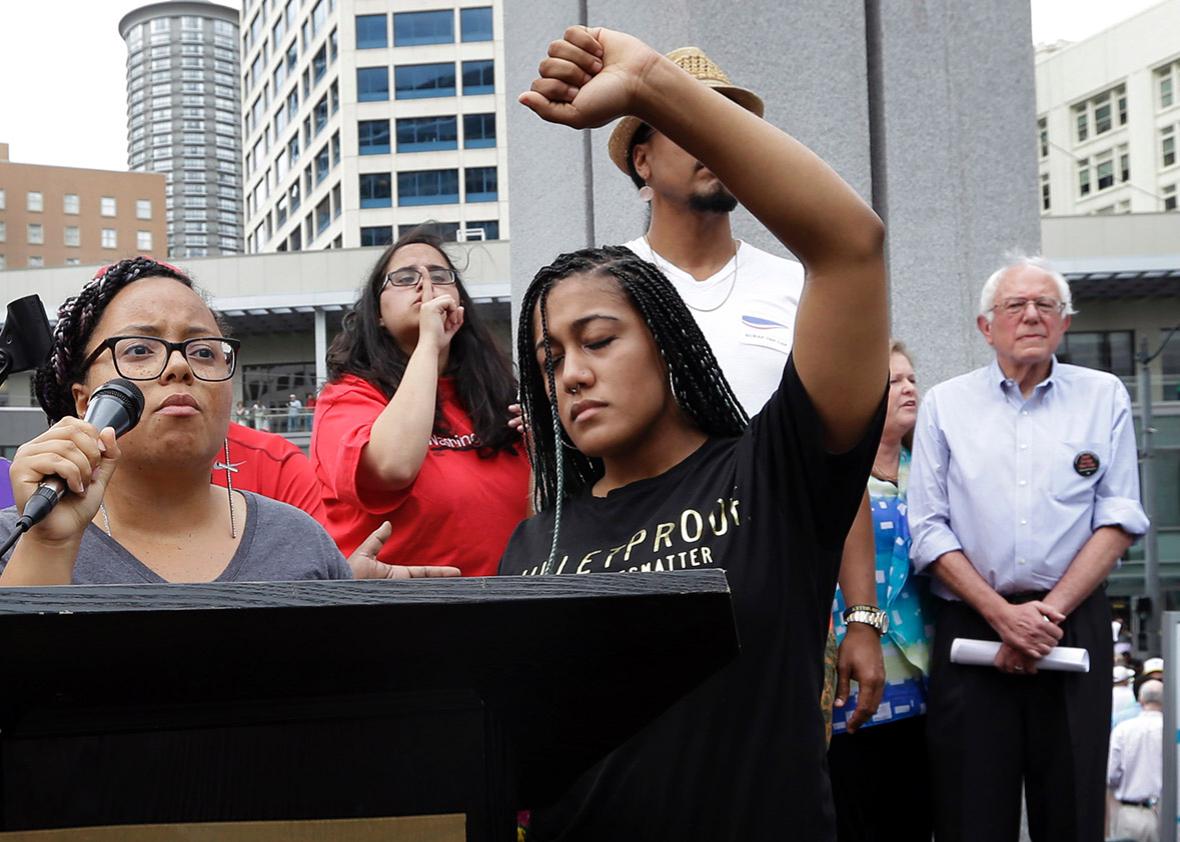

Last week, for instance, protesters associated with Black Lives Matter interrupted a Sanders rally in Seattle. As with the first interruption, in July, this sparked days of intra-left debate and disagreement. Here’s Nolan, again: “For those perceptive enough to separate pretty slogans from actual policy prescriptions, it is clear that Bernie Sanders is the candidate most aligned with the group’s values,” he wrote, critiquing the demonstrators. “Stifling his voice only helps his opponents.”

On the other side are writers like New Republic editor Jamil Smith, who are much more sympathetic to the Black Lives Matter activists. “I’m not against criticizing activist tactics,” he wrote, “but the idea that Black Lives Matter protesters are hurting their cause by challenging candidates, even those considered allies, is based in the notion that the burden of making change is on them. It isn’t.”

Part of the problem in this debate—and why it’s so frustrating to its participants—is that no one has tried to answer the “why” question. Instead, the argument is over tactics, excess, and the prerogatives and responsibilities that come with protesting. Should Black Lives Matter go easy on Sanders? Is the message more important than the particular tactic?

Set those questions aside, however, and you have an easy answer for why Sanders gets the brunt of Black Lives Matter activity, at least among Democratic presidential candidates. Unlike his competitors, Sanders is simply the best available vessel for bringing activists’ concerns to the mainstream of the Democratic Party.

The picture might be different if Sanders were more marginal and on the periphery of the nomination fight (like former Virginia Sen. Jim Webb). As it stands, the Vermont senator is the leading alternative to frontrunner Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary. He earns almost 20 percent or more in most national polls of the race, and is effectively tied for first in New Hampshire. He also dwarfs any other candidate for president—in either party—in terms of shear crowd size: 27,000 in Los Angeles, 28,000 in Portland, Oregon, and 15,000 in Seattle, where his speech was interrupted last week.

At the same time, Sanders doesn’t have the tightly closed-down campaign of Hillary Clinton. He is accessible, as evidenced by the ease with which activists have reached him on stage. And while he’s been clumsy in these incidents, he also hasn’t lashed out. In both cases, he ceded the mic. Compare that to the attempted Black Lives Matter protest at a Clinton rally in New Hampshire. Activists reached the event, but they couldn’t get past security to announce their presence.

In this environment, if you’re trying to make a splash, you go with Sanders, especially when he’s more open to change and adjustment than the alternatives. Disrupting Sanders gives you more bang for your buck: It keeps you in the news and puts indirect pressure on other campaigns that know they’ll have to answer to the movement’s questions. To that point, the New Hampshire demonstrators couldn’t crash the Clinton rally, but they still met with the candidate—quietly—and discussed their concerns. In all likelihood, the pressure on Sanders has forced Clinton—the likely nominee—to devote more time to Black Lives Matter, in a bid to protect her flank. And in turn, this brings their issues up the ladder, closer to the top of the party’s agenda.

Black Lives Matter isn’t a single organization—it is a loose collection of groups and individuals, unified by a common cause, under a single banner. While there’s coordination, there’s no guarantee that different groups of activists are working together. But that doesn’t mean the movement isn’t rational or strategic. And if we look at it as both, then its approach to the Democratic primary begins to make sense, even if it’s messy.