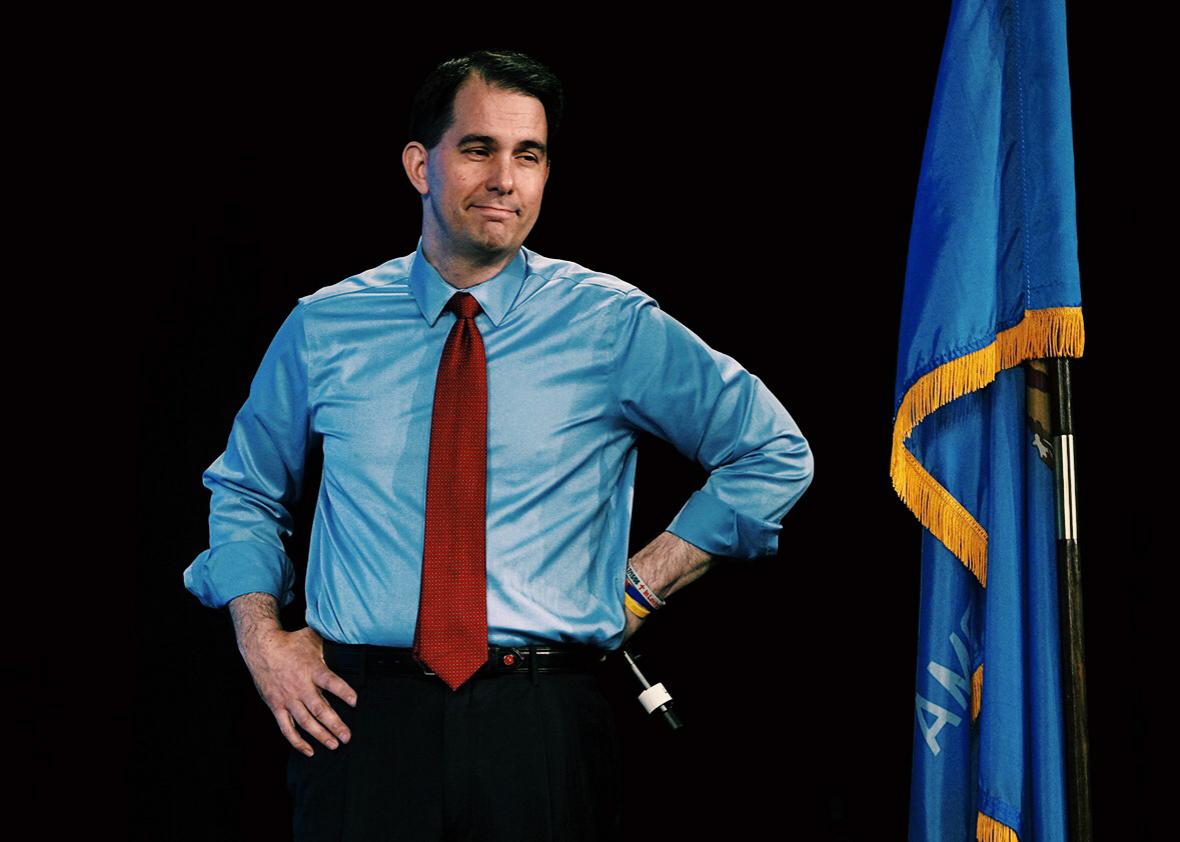

After six months of speeches, fundraisers, and cattle calls, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker is making it official: He’s running for president. Unlike most other candidates in this overstuffed melee of a nomination fight—thus far, there are 15 formal candidates for the GOP crown—Walker is a candidate to beat, and perhaps the candidate to beat.

Like Ted Cruz or Mike Huckabee, Walker appeals to conservative Republicans. But his vehicle is action, not petty outrage or high-wire antics: With every successful fight against liberal interest groups—from unions to academics—he wins more acclaim from the right’s rank and file. At the same time, his restrained rhetoric and cautious demeanor gives him an opening with Republican elites, who want a strong—but measured—nominee. Add his fundraising prowess to the mix and you have a base-driven candidate with “establishment” bona fides who doesn’t alienate the other factions of the Republican Party—a potent profile for a presidential hopeful.

In terms of stagecraft, the most important fact about Walker is his affable, if boring, presentation. Despite his right-wing views on everything under the sun—from worker’s rights and economic regulation to climate change and voter access—he seems like an ordinary accountant or middle-manager who just wants to put a few things in order. And to bolster that image, Walker touts his “everyman” bona fides—his reliance on the Kohl’s department store for clothing and other everyday items—and stresses his experience in the Wisconsin governor’s mansion.

For Walker, there’s nothing he might face as president that doesn’t have an analogue in Madison’s statehouse. When asked how he’d handle ISIS, for example, Walker told an audience at the Conservative Political Action Conference in February that if he can “take on 100,000 protesters”—a nod to the 2012 recall election—he can “do the same across the globe.” Indeed, he’s all but summarized his pitch to Republican voters—and the nation writ large—with a single line: “Governors,” he said in a 2014 interview, “make much better presidents than members of Congress.”

Unfortunately for Walker, it’s not clear that the GOP public agrees. Of the past six Republican presidential nominees—Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bob Dole, George W. Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney—three were governors, and three were lawmakers of one shape or another. Likewise, it’s also unclear if this assertion—key to Walker’s general pitch—is true, period.

Since the end of World War II, we’ve had 12 presidents. Four were governors before entering the White House (Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush), two were senators (John F. Kennedy and Barack Obama), four were vice presidents (Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and George H.W. Bush), and two had unusual pre-election backgrounds: Dwight Eisenhower was a general, and Gerald Ford was House minority leader turned replacement vice president turned incumbent after Nixon’s resignation.

It would be one thing if the governors had stellar records and their peers were less successful. But the truth is that we’re looking at a collection of mixed records. Among the gubernatorial presidents, neither Carter nor Bush had successful presidencies, at least judged in political terms: Carter blundered through four years and lost re-election, while Bush led the country into two wars and an economic crisis, nearly crippling the GOP in the process. On the other side, Reagan and Clinton had considerable political success but mixed records of terrible inaction and foolhardy changes to the status quo (although Reagan stands as one of the most substantively conservative presidents of the postwar period).

The senators, likewise, have mixed records. Despite his huge presence in America’s political mythology, Kennedy was a middling president whose stature owes more to his sudden death than it does to any actual accomplishment. It’s still too early to judge Obama’s administration, but at the moment, it’s fair to say that he’s been a consequential steward of the United States, shepherding the nation through a global recession, a large expansion of the federal government, demographic changes, and seismic shifts to American cultural life.

It seems obvious, but if there’s any experience with a clear connection to presidential success, it’s vice presidential experience. Even the worst-off vice presidents—estranged from their presidents and burdened with trivial responsibilities—gain valuable skills from their experience in close proximity to the Oval Office. They build strong political networks, hone their ability to speak to large crowds, and most importantly learn to engage and operate in the federal bureaucracy. The least glamorous part of the presidency is the bureaucracy; a given White House is responsible for staffing thousands of positions across every department of the federal government. At the same time, however, this is vital to the effective exercise of presidential power. A president who isn’t able to exert his will through the bureaucracy is a president who is hamstrung in his ability to make policy and potentially vulnerable to mistakes, missteps, and disasters in those federal agencies. The catastrophe of healthcare.gov—which wounded the Affordable Care Act at a critical moment—is a perfect example of the perils of a weak hold on the bureaucracy. (Obama, in fact, has been unusually bad at using and utilizing bureaucratic power.)

What’s striking about the presidents with vice presidential pedigree (and Eisenhower, for that matter, who served at the highest summit of the military bureaucracy) is that they were highly effective with bureaucratic levers as well as political and congressional ones. It is a consistent fact of their administrations in a way that isn’t true of every president with gubernatorial experience (George W. Bush is the possible exception). Johnson entrenched his Great Society and civil rights reforms with agencies devoted to accomplishing these goals; Nixon defused political opponents by co-opting them and their goals into his administration; and George H.W. Bush entrenched conservative priorities at the judicial level of American government, appointing more judges in a single term than any president other than Franklin Roosevelt.

To get back to Walker, there’s nothing about his experience as governor that makes him plainly superior to his competitors from the Senate and elsewhere. In fact, he may have the one glaring weakness of governors-turned–presidential candidates: micromanagement. On Saturday, the New York Times described a Walker who has “long been his own strategist,” who thinks like a “political operative,” and who has a tendency to “play consultant.” In the context of state governance and state campaigns, the hands-on approach can work well. But at the national level, it can lead to big missteps and larger mistakes. Just ask Jimmy Carter. Or Michael Dukakis.