On Wednesday night, a white man walked into a black church in Charleston, South Carolina. He sat with 12 congregants at a Bible study meeting for an hour. Then he stood up and shot nine of them to death. According to a survivor, the killer told his victims: “You rape our women, and you’re taking over our country, and you have to go.”

The country is in shock. We’re faced with demons we’ve repeatedly tried to bury: racism, gun violence, mental illness. There are cries for justice, reconciliation, and awakening. There’s hope that something good, some change in our culture, can come out of this.

Don’t count on it. Tucson, Arizona; Aurora, Colorado; and Sandy Hook didn’t persuade Congress to require universal background checks for gun purchases.* And the long history of crimes against black churches has never aroused much concern among whites. Even the worst attack on a black congregation—the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama—didn’t, by itself, measurably affect white public opinion.

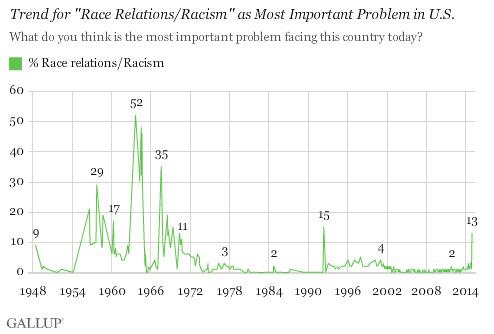

Twenty years ago, church arsons were a national plague. From January 1995 to September 1998, the National Church Arson Task Force reported 670 arsons, bombings, or bombing attempts at houses of worship. Of these incidents, 225 involved black churches. During this period, in 10 separate polls, Gallup asked Americans to name the most important problem facing the country. Not once did the percentage that named race relations rise above 5 percent.

Gallup

Gallup has been asking this question for two-thirds of a century. When you look at its graph of responses over the decades, a few spikes stand out. These are moments when race relations attracted the attention and concern of a lot of whites. The first spike marked with a number is in October 1957, just after the school integration showdown in Little Rock, Arkansas. In that poll, 29 percent of Americans said race was the top issue. The last spike marked on the graph is in May 1992, a week after the Rodney King verdict. You can see how quickly the public’s concern, after that blip, sank back to its previous level. But the biggest spike, by far, occurred in a survey taken from Sept. 12–17, 1963. In that sample, 52 percent of respondents said race was the country’s most important problem.

What happened in September 1963? A fatal attack on a black church. On Sept. 15, a bomb planted by white racists exploded at the 16th Street Baptist Church during Sunday school. It killed four girls. Later that day, two black boys died in Birmingham as violence erupted around the city.

The nation was transfixed. A week after the tragedy, there were demonstrations in many cities. The estimated attendance was 1,500 in Miami, 7,000 in New York, 10,000 in Boston, and 10,000 in Washington. But did the bombing trigger an outbreak of reflection or conscience in America? I can’t find much evidence that it did.

Nobody seems to have surveyed the public about the incident. The best we can do is to look for changes in surveys taken before and afterward. And we can’t use that big surge on Gallup’s “most important problem” question, because the bombing didn’t happen until the fourth day of Gallup’s six-day survey. Gallup has no record of how many of the interviews had been done by then. It’s much more likely that the main cause of the spike was the March on Washington, which took place on Aug. 28 of that year.

Two pollsters can shed some light on the extent to which public opinion shifted, or didn’t, in the latter months of 1963. One is Gallup. In a 1999 review, Gallup discussed three surveys it conducted during that period. In the first sample, taken in June 1963, the percentage of respondents who favored “racial equality in public places” (Gallup’s review doesn’t specify how the question was phrased) stood at 49 percent. In the next sample, taken in August 1963, it rose to 54 percent. In the third sample, taken in January 1964, it reached 61 percent. That’s a big change in a short time. But it’s not clear to what degree white-on-black violence—as opposed to the rally in Washington, the assassination of President Kennedy, or the emerging debate over the Civil Rights Act—drove the change.

Another polling organization, the National Opinion Research Center, surveyed the public in May, November, and December 1963. The November poll is useful because it separates the events of that fall, including the Birmingham bombing, from Kennedy’s assassination. Between May and November, the percentage of respondents who said that black and white students “should go to the same schools” increased slightly among people who had only a high school education. But it decreased among college-educated Southerners and among people who had less than a grade school education. When all education groups were combined, the data showed that from May to December, the percentage of respondents who favored the “same schools” option didn’t change while the percentage who preferred “separate schools” increased by 3 points. NORC also asked whether “there should be separate sections for Negroes in streetcars and buses.” More people said no than yes. But from May to December, the gap in favor of integration declined by 3 percentage points.

NORC, like Gallup, asked one question that showed positive movement during this time. The question was: “If a Negro with the same income and education as you have, moved into your block, would it make any difference to you?” From May to December 1963, the percentage of white respondents who said it would make no difference increased among Southerners with a high school or college education. But it didn’t change among Northerners or less educated Southerners.

Polls aren’t the only way to measure sentiment. In Mobilizing Public Opinion, a reassessment of the civil rights era, political scientist Taeku Lee analyzed a random sample of nearly 7,000 race-related letters that were mailed to the White House from 1948 to 1965. The letters, sent by ordinary citizens, were coded by position (for or against racial equality or civil rights) and date. Lee’s graphs of the resulting data suggest that during the last two quarters of 1963, the volume of race-related mail subsided to less than half of what it had been earlier in the year, and the letters tilted overwhelmingly against civil rights.

If these numbers depress you, cheer up. The scale of cultural progress during these decades was, by previous standards, spectacular. An analysis of polls from 1942 to 1983, compiled in the definitive volume Racial Attitudes in America, shows that white people’s attitudes improved by 58 percentage points on school integration, 52 points on equal employment, and 49 points on openness to black neighbors. In 1958, only 37 percent of whites said they would vote for a “well-qualified man for president” if he were black and were nominated by their own party. Twenty years later, that number had doubled. Thirty years after that, a black man was elected president.

But the change took time. It required more than the deaths of those four girls in Birmingham. It took Emmett Till, Medgar Evers, James Chaney, and Martin Luther King Jr. It took many more bombings and burnings of churches. It took fire hoses, batons, bullets, and blood.

What happened in Charleston is a reminder that civil rights laws and a black president didn’t make us angels. It’s easy to hate, and when you have a gun and no conscience, it’s easy to kill. And when the people who died don’t look like you, it’s easy to turn away and forget. You don’t have to think about how these things happen, and what we can do to prevent them, until the next time. I hope we won’t wait till the next time. But history says we will.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the Charleston shooting.

*Correction, June 20, 2015: I originally misstated that the mass shootings in Tucson, Aurora, and Sandy Hook hadn’t persuaded Congress to require background checks for gun purchases. That was sloppy. Background checks are required for purchases from federally licensed firearm dealers. The legislation rejected by Congress would have extended the background-check requirement to sales at gun shows and over the Internet.