The gay marriage war is over. The polygamy war is on.

Social conservatives have warned about polygamy for years. They see it as the next step down the slippery slope of “redefining marriage.” Friday’s ruling in favor of same-sex marriage doesn’t end the legal wrangling over the rights of religious objectors. It certainly doesn’t end the political or cultural debate about homosexuality. But in their dissents, and in their questions during oral argument, the court’s conservative justices have thrown their weight behind a new issue. They’re demanding to know why, if gay marriage is a constitutional right, polygamy isn’t.

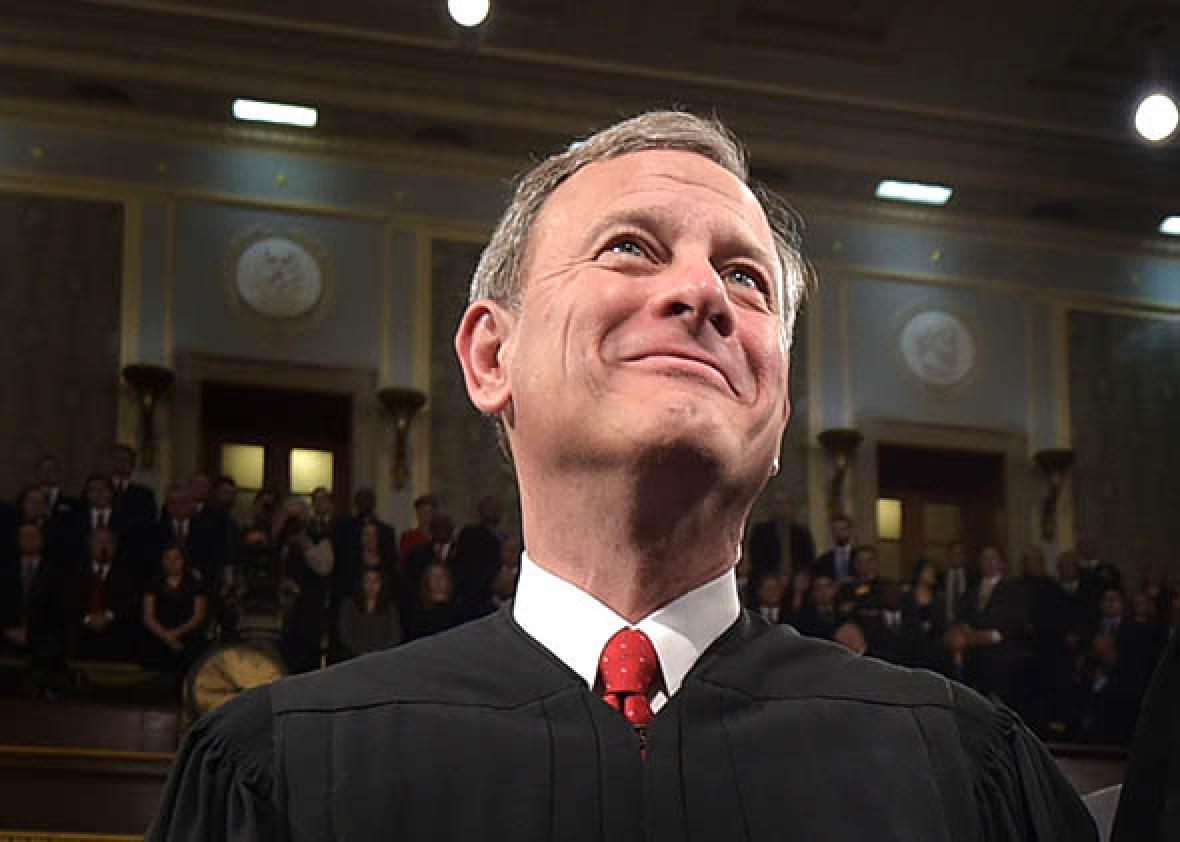

At Obergefell v. Hodges oral arguments on April 28, Justice Samuel Alito asked on what grounds a state could deny a marriage license to a foursome of two men and two women. Justice Antonin Scalia asked whether states should be required to recognize polygamous marriages performed in countries where the practice is legal. Then, in his dissent issued Friday, Chief Justice John Roberts contended that “much of the majority’s reasoning” in support of same-sex marriage “would apply with equal force to the claim of a fundamental right to plural marriage”:

Although the majority randomly inserts the adjective “two” in various places, it offers no reason at all why the two-person element of the core definition of marriage may be preserved while the man-woman element may not. Indeed, from the standpoint of history and tradition, a leap from opposite-sex marriage to same-sex marriage is much greater than one from a two-person union to plural unions, which have deep roots in some cultures around the world.

Roberts is partially right. The majority opinion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, is full of arguments for gay marriage that could just as easily justify polygamy. But Roberts is wrong when he claims that Kennedy has offered “no reason at all” why the law should treat polygamy differently from homosexuality. The majority opinion offers several good reasons. It just doesn’t explain how they apply to plural marriage.

Let’s do that now. Does the court’s reasoning in Obergefell distinguish gay marriage from polygamy?

If you want to assert a right to plural marriage, you can certainly find some basis in Kennedy’s opinion. He says that “the right to personal choice regarding marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy,” and he compares the choice of one’s spouse to “choices concerning contraception” or procreation. Roberts replies, rightly, that if the underlying principle is the individual’s “autonomy to make such profound choices,” it’s hard to see why that autonomy shouldn’t extend to choosing additional life partners.

Kennedy also complains that laws against same-sex marriage “demean” and “disrespect” gays and lesbians. He says such laws “disparage their choices and diminish their personhood,” “humiliate the children of same-sex couples,” and impose on these children “the stigma of knowing their families are somehow lesser.” Roberts points out—again, correctly—that the same could be said of laws denying recognition to polygamous partners and their children.

The most awkward argument, in terms of its bearing on polygamy, is Kennedy’s praise for marriage as a joint enterprise. Through matrimony, he writes, “two persons together can find other freedoms, such as expression, intimacy, and spirituality.” He concludes: “In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were.” But if two is better than one, why isn’t four better than two?

These resemblances between Obergefell’s reasoning and the rationale for legalized polygamy ought to prompt reflection, particularly if you claim to support “marriage equality.” But the resemblances are only half the story. The other half, which Roberts ignores, are Kennedy’s additional considerations, many of which favor same-sex marriage but not marriage to more than one partner. Kennedy does a lousy job of clarifying these considerations. Let’s spell them out.

1. Immutability. Kennedy tosses this into his opinion, bizarrely, as a side comment. Referring to gays who seek matrimony, he says, “[T]heir immutable nature dictates that same-sex marriage is their only real path to this profound commitment.” Later, he speaks of “new insights” that have transformed society, including this one: “Only in more recent years have psychiatrists and others recognized that sexual orientation is both a normal expression of human sexuality and immutable.” Kennedy doesn’t elaborate on these remarks, but they’re huge. Immutability is the biggest difference between homosexuality and polyamory. Even the pro-polyamory law review article cited by Roberts in his dissent acknowledges that immutability is a crucial factor in identifying unjust discrimination against classes of people—and that “polygamists are not born that way.”

2. Loneliness. According to Kennedy, “Marriage responds to the universal fear that a lonely person might call out only to find no one there. It offers the hope of companionship and understanding and assurance that while both still live there will be someone to care for the other.” At the end of his opinion, Kennedy returns to this theme. He says gay people who are legally excluded from marriage are “condemned to live in loneliness.” You can’t say that about polyamorists. Legally, they may be condemned to monogamy. But not to solitude.

3. Exclusion. Kennedy notes that when laws forbid gay marriage, “same-sex couples are denied all the benefits afforded to opposite-sex couples.” He lists many such benefits, including tax breaks, inheritance rights, property rights, adoption rights, hospital visitation, survivor benefits, and health insurance. He also points out that children in same-sex households “suffer the significant material costs of being raised by unmarried parents.” That’s not true for kids in polyamorous households. Their parents can marry—they just have to pair up, leaving one adult, at most, unaccounted for. And when they do, each couple gets the same spousal benefits as a monogamous couple.

4. Divided loyalty. Kennedy says marriage “embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family.” He doesn’t explain how these ideals distinguish homosexuality from polygamy. But they do. Fidelity and devotion are concentrated virtues. When you spread them out among multiple spouses (or, yes, even among children—that means you, Duggars), you dilute them. One article cited by Roberts notes that many polyamorists are “polyfidelitous,” which means they “don’t date outside their ménage.” But when you’re free to have sex with anyone inside the ménage, or to spend the weekend with this spouse instead of that one, the value of your fidelity and devotion are diminished, just as surely as inflation shrinks the value of a dollar.

5. Conflict. Countless marriages have exploded and ended because two spouses couldn’t get along. With three or four spouses, it’s that much harder to keep everyone happy. Kennedy doesn’t talk about this, but Mary Bonauto, an attorney representing gay couples in Obergefell, discussed it during oral argument. When Alito asked her why states should have to recognize gay marriages but not plural marriages—and forced her to address the scenario of two men and two women in a foursome, which bypasses the usual complaint about underage or patriarchal polygamy—Bonauto replied that plural marriage might raise valid governmental concerns about “disrupting family relationships.” For example, she asked: “If there’s a divorce from the second wife, does that mean the fourth wife has access to the child of the second wife?”

That’s a good question. Look at the 2009 Newsweek story Roberts cites in his dissent. The article describes jealousy in a polyamorous triad: “Scott had a hard time the first time he heard Larry call Terisa ‘sweetie,’ ” and sometimes “Scott has had to put up with hearing his girlfriend have sex with someone else in the home they share.” The tension extends to a 6-year-old boy who’s the biological child of one woman in the group. “Recently, the child asked his father who he loved more: Mommy or Terisa,” says the article. The boy’s father says he told the boy, “ ‘Of course I love momma more,’ because that’s the answer he needed to hear.” Polyamory is all about and equality and honesty, until it isn’t.

That’s why it’s so odd to see Roberts suggest, in his dissent, that gay marriage is a bigger leap than polygamy is. Douglas Hallward-Driemeier, another Obergefell lawyer, argued the opposite during oral argument. Responding to Scalia, Hallward-Driemeier pointed out that extending marriage to same-sex couples has been far simpler than polygamy would be, precisely because gay and straight marriage are so alike. In states whose laws have been judicially overturned, he observed, “All that has happened under their laws is that they have had to remove gender-specific language and substitute it with gender-neutral language.”

The more you learn about polyamory, the more you appreciate, in retrospect, the simplicity of same-sex marriage. It’s two people, each one wholly committed to the other. It’s a minimal demand: one spouse, just like everybody else. So go right ahead, Mr. Chief Justice. Bring on the polygamy debate. It will make gay marriage positively boring.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the Supreme Court’s same-sex marriage ruling.