Among the most awkward moments of Hillary Clinton’s last campaign for president was her speech in Selma, Alabama, on the 42nd anniversary of Bloody Sunday. The substance of her speech was unremarkable, but the style was unfortunate. Clinton tried to soar with inspirational rhetoric—“Yes, that long march to freedom that began here has carried us a mighty long way”—but it fell flat. And worse, the Chicago-raised Clinton adopted a strange Southern drawl that at times mimicked, poorly, the cadences and rhythms of a black preacher. Instead of connecting with her audience, Clinton—who has real allies in black political leadership and a genuine commitment to voting rights—looked fake.

When we talk about Clinton, we often talk about this inauthenticity. “Despite sharing her husband’s poll-driven risk aversion,” wrote columnist Damon Linker in a piece last year for the Week, “Hillary Clinton has never played the game on his level, and her vulnerability to backlash against gratuitous displays of patent insincerity is already becoming glaringly apparent.” Linker’s view is a version of former Clinton adviser Mark Penn’s: “Hillary is cold, removed, needs to be authentic,” he said, suggesting she be “as likable as possible” but not “reach too far.” And in turn, this reflects a more hostile assessment from conservative speechwriter Peggy Noonan in her 2000 book The Case Against Hillary Clinton, “She lacks historical heft, is not a person of real size and authenticity.” Carl Bernstein, discussing his biography of Clinton, said it this way: “This is a woman who led a camouflaged life and continues to.”

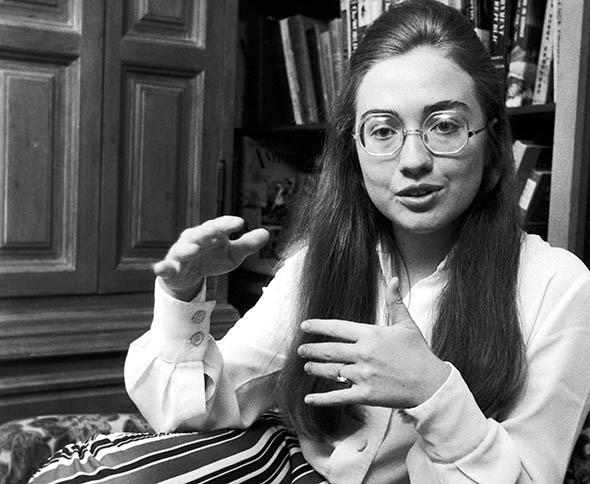

Courtesy of Wellesley College Archives/Photo by Stimmell

But there’s an obvious double standard here: What politician is utterly authentic? Who are the lawmakers who show their realest selves to the public? And what does it even mean to be “authentic” in a singular sense when all of us are authentic in different ways at different times?

For Clinton in particular, this entire line of questioning and criticism is deeply unfair. After all, there was a time when Hillary Clinton was incredibly authentic, or, at least, gave us a glance at one of her authentic selves. “One needn’t approve of what she says or does (though often it is highly approvable) to recognize her as real,” wrote journalist Paul Greenberg in 1992, during the Democratic primaries. At the New Republic, Elspeth Reeve uncovers a 1992 profile of Clinton in which observers and reporters praise her as “charming,” “delightful,” “extraordinary,” and “unbelievably articulate.” This Hillary Clinton—still new on the national stage—was ambitious, driven, and feisty. She was as political, knowledgeable, and as fluent in the language of policy as her husband. And people liked her for it.

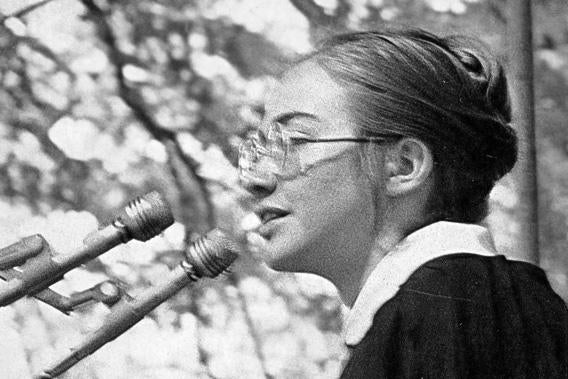

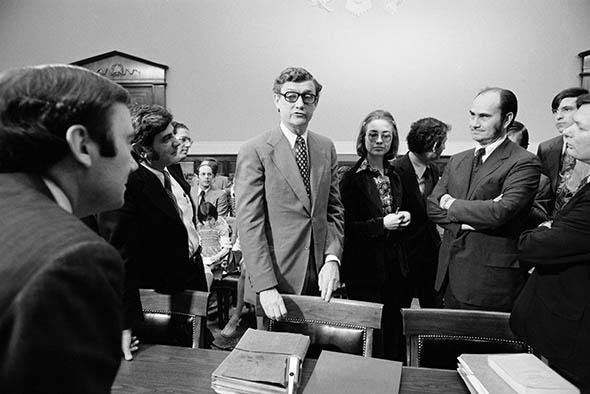

Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images

Or they did, until she revealed too much. “I suppose I could have stayed home and baked cookies and had teas, but what I decided to do was to fulfill my profession which I entered before my husband was in public life,” she said to reporters about her career, unleashing waves of criticism from angry and affronted Americans. Clinton was too real, and she paid a political price. Hillary and her allies would spend the next two decades, right up to the present, burying the tough, passionate Clinton and playing up the one who wouldn’t raise hackles, who was her “softer side” more than she was a political partner.

Photo by Ron Galella

But even as Clinton has accommodated the backlash, she chafes against it. According to Gail Sheehy, who has profiled Clinton and been her biographer, the former first lady once confessed deep frustration with her public image. “I just don’t know what to do anymore, nothing I do works. … I understand that I’m really threatening to men, that the velocity of change between men and women and the way the country is going and for one generation to the boomers is overwhelming, especially to men,” she said. “I’m threatening to them and I don’t know what to do about it.” Clinton came back to this territory during her 2000 Senate campaign, during an unusually introspective press conference. “ ‘Who are you?’ and all of that. I don’t know if that is the right question,” she said. “Even people you think you know extremely well, do you know their entire personality? Do they, at every point you’re with them, reveal totally who they are? Of course not. We now expect people in the public arena to somehow do that. I don’t understand the need behind that.”

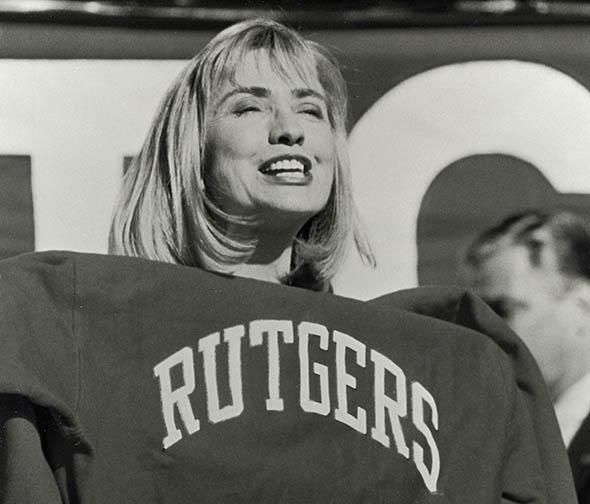

Photo by Cynthia Johnson/Liaison

Hillary Clinton is running for president again, and it’s clear she’s still accommodating the backlash against her more authentic self. Unlike her Republican opponents who announced their campaigns with big rallies and elaborate staging, Clinton had a quieter initial rollout. She released a short video—focused entirely on her supporters—and embarked on a “listening tour” across early-primary and swing states. All of this was meant to diffuse the sense that Clinton is entitled—a “coronated” candidate foisted on an apathetic party. I don’t know if that has worked, although I think the description is false. What I can say, however, is that these scripted events have made her seem more relatable and more real. Just not in the way you might expect.

During her “listening tour,” Clinton spoke to Iowans about substance abuse, mental illness, and building treatment capacity for both; to Nevada high schoolers about immigration reform, vowing to “do everything I possibly can” to help immigrants; and to community college students about job training and education. And in speeches across the country, she’s staked new and more liberal ground on criminal justice reform and voting rights, pushing an expansive plan for universal voter registration.

What comes across in every instance is her enthusiasm for policy. When the discussion is concrete, when it involves problems and solutions, Clinton is clear and compelling. No, she doesn’t have the effortless charm of her husband or the equally effortless cool of Barack Obama, but she’s intense, devoted, and honestly interested in helping. Here’s the New York Times on her stop in New Hampshire:

There is not a lot of I-feel-your-pain hugging at these events, and few uproarious moments. But Mrs. Clinton brings a wonkish intensity, arriving at each round table armed with specific data points. She said, “The average four-year graduate in Iowa graduates with nearly $30,000 in debt,” and, “In New Hampshire, 96 percent of all businesses are considered small businesses.” She nods, jots down notes and interjects conversations with words of encouragement: “That’s interesting,” and, “That’s a very good point.”

There’s another way to put this: Hillary Clinton is a nerd. You see it at every stage of her life. As a kid she went door to door collecting census data, asking homeowners if they had “any children in the home who are not in school” so that the Census Bureau could understand the discrepancy between the total number of children and those who are enrolled in school. As a student at Wellesley, writes Carl Bernstein, she developed “a better system for the return of library books” and “studied every aspect of the Wellesley curriculum in developing a successful plan to reduce the number of required courses.” Writing in the Atlantic, Peter Beinart collects other examples of Clinton’s earnest, and authentic, nerdiness:

In 1993, she took time off from a vacation in Hawaii to grill local officials about the state’s healthcare system. In his excellent book on Hillary’s 2000 Senate race, Michael Tomasky observes that, “In the entire campaign, she had exactly one truly inspiring moment” but that, “over time it became evident to all but the most cynical that she actually cared about utility rates.”

Looking ahead to 2016, Clinton will face one of two attacks from her eventual Republican opponent, if not both: that she can’t relate to ordinary Americans, and that she’s long in the tooth—a candidate for yesterday, not tomorrow.

An elite among elites, there’s no way that Clinton can refute the latter. But she can sidestep it, and take on the former, by embracing the ambition, the earnest wonkery, and the nerdy enthusiasm that have defined her entire life. Instead of moderating the parts of her that caused her trouble in 1992 (and beyond), she should step on the throttle and ride with them. Not only does it fit her, but it fits the moment, too.

Photo by Curtis Means/NBC NewsWire

Earlier this year Parks and Recreation ended its seven-season run on NBC. Initially modeled on the American version of The Office, the show shifted gears in its second season. It became gentler—a comedy of errors, not a comedy of awkwardness—and in its own way, radical. As critic Alyssa Rosenberg wrote for the Washington Post, rather than capitulate to the hopelessness of present politics—in which gridlock and obstruction are the rule—Parks and Recreation stood out as a “celebration” of government that “distinguished itself from other television that’s broadly considered liberal (and from so much of real-world politics), by arguing for a theory of change and a specific role for government.”

It did this through its heroine, Leslie Knope, played with aplomb by comedian Amy Poehler. For seven seasons, viewers could watch Knope—a talented and dedicated public servant—make the case that government, when used with passion and integrity, can be a force for good. Yes, the projects were often minor: a festival here, a park there. And her obstacles weren’t hostile politicians as much as they were bumbling citizens and indifferent colleagues. But her basic philosophy was one of civic engagement. “I am very angry. I’m angry that Bobby Newport would hold this town hostage and threaten to leave if you don’t give him what he wants. … Corporations are not allowed to dictate what a city needs. That power belongs to the people,” said Knope in fourth-season debate with a political opponent. And in the season finale, Leslie gave her final take on what it means to be a public servant. “When we worked here together, we fought, scratched, and clawed to make people’s lives a tiny bit better,” she said. “That’s what public service is about: small, incremental change every day.”

Twenty years ago a character like this might have had a sharper, more negative edge, like Reese Witherspoon’s Tracy Flick in Election. Now, however, she’s admired. And while Knope isn’t a Hillary Clinton surrogate—although she keeps a photo of Clinton in her office—you can read her as a sunny take on the Clinton type: tenacious, ambitious, and incredibly smart.

Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Parks and Recreation wasn’t a blockbuster series, but it was popular. And in its popularity, it showed a greater appetite for the kind of woman reflected in Knope. Indeed, it’s no accident that, in 2015, Poehler—and her former Saturday Night Live colleague Tina Fey—have become feminist celebrity icons on the strength of these kinds of characters and performances.

The Hillary Clinton of 1992—long buried by controversy, circumstance, and political necessity—would have thrived in this moment. Indeed, today’s world is much more ready for the kind of woman who would snark about baking cookies on national television.

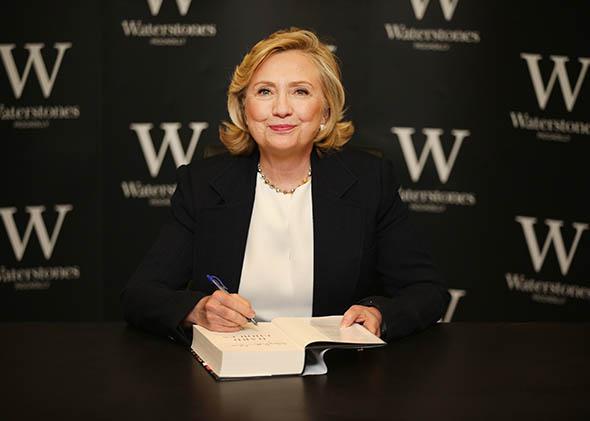

Photo by Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images

In an environment where voters want someone new, but also want constructive progress, “Hillary as civics nerd” is appealing. And it seems Clinton is making that bet, leaning on her past as a wonk and an advocate to connect to Democratic voters, while channeling the punchy confidence of her national debut. “I may not be the youngest candidate in this race,” she said in her inaugural campaign speech on Saturday, “but I will be the youngest woman president in the history of the United States.”

Rather than wow the audience with rhetoric, Clinton structured her speech with policy, giving the audience a clear view of what she would do for the country—the battles she would “fight”—if elected president. She would protect and improve the Affordable Care Act; push a higher minimum wage; change the tax code to rein in Wall Street; cut small-business taxes; build green infrastructure; provide job training and aid for “distressed” communities; pass universal paid leave and child care; make college debt-free; ban discrimination against LGBT Americans; and make retirement more secure.

If Clinton had tried to mimic Obama—tried to inspire Americans like the president she wants to succeed—it would have rung false. Instead, she talked policy and told thousands of people exactly what she would do.

It was a necessary speech, and Clinton is strongest when she sticks with the concrete—the nuts and bolts of government. That was true in her 2000 Senate race, it was true during the best moments of her 2008 presidential campaign, and it’s true now. And so, as she reintroduces herself to the Democratic Party, and the American electorate as a whole, she should embrace her nerdiness. Not only is it effective—a persona perfect for a moment when Americans want solutions more than inspiration—but, after years of keeping it under wraps, it’s the most authentic move she could make.