Thus far, the Democrats’ anti-inequality agenda has focused on redistribution. Barack Obama wants free community college and tax credits for child care, congressional Democrats want a $12 minimum wage, and Hillary Clinton has endorsed paid family leave. But scholars at the forefront of the inequality battle want Democrats to go even further.

“To fix the economy for average Americans,” writes Joseph Stiglitz and his team of fellow economists in a report for the left-leaning Roosevelt Institute titled “Rewriting the Rules: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity,” “we need to tackle the rules and institutions that have generated low investment, sluggish growth, and runaway incomes and wealth accumulation at the top and created a steeper hill for the rest to climb. It would be easier, politically, to push for one or two policies on which we have consensus, but that approach would be insufficient to match the severity of the problems posed by rising inequality.”

In an unequal economy, they argue, it’s not enough to redistribute the gains of a tiny, wealthy minority. Even with more programs—more health care, more tax credits—the shape of the economy is the same: The wealthiest individuals and corporations receive the lion’s share of national income. And that’s by design. “Inequality has been a choice,” writes Stiglitz and his team. “Beginning in the 1970s, a wave of deliberate ideological, institutional, and legal changes began to reconfigure the marketplace. … Get government out of the way and the creativity of the marketplace—and the ingenuity of the financial sector—would revitalize society.” Put differently, the “deregulation” of the 1980s and 1990s was really a “re-regulation”—“a new set of rules for governing the economy that favors a specific set of actors.”

And it failed. Labor force participation sits at a 37-year low, public and private investment is weak, and tens of millions of Americans struggle with slow growth and low wages. Greater redistribution can ameliorate these problems, but it can’t solve them.

For that, you need to rethink the markets themselves. You need new rules to build an economy that delivers more equal results before the government steps in to tax and spend. In short, Stiglitz and company recommend greater financial regulation—ending “too big too fail” and creating greater transparency in financial markets—incentives for long-term business growth (including a financial transaction tax to discourage short-term trading and “encourage more productive long-term investment”); higher taxes on capital gains, dividends, and corporate income; and a national commitment to full employment, through public works and monetary policy. And to deliver more gains to ordinary people, they call for stronger bargaining rights and lower barriers to unionization, criminal justice reform, pay equity, health care reform (“Medicare-for-all”), and a host of new programs for children (universal pre-K, child benefits), retirees, and homeowners (a public option for mortgages).

The bulk of this plan is far afield from the mainstream of the Democratic Party. Which means it runs far afield from Hillary Clinton, who stands at the center of the Democratic coalition. What’s more, from the Clinton administration to her time in the Senate, Clinton has held close ties to the Wall Street wing of the Democratic Party, which favors the kind of financial deregulation that produced yawning inequality and a catastrophic economic collapse. It is one thing to push Clinton on immigration and criminal justice reform—areas where the coalition has moved to the left. It’s something different, and more difficult, to push her toward a fundamental revamp of our economy and its rules.

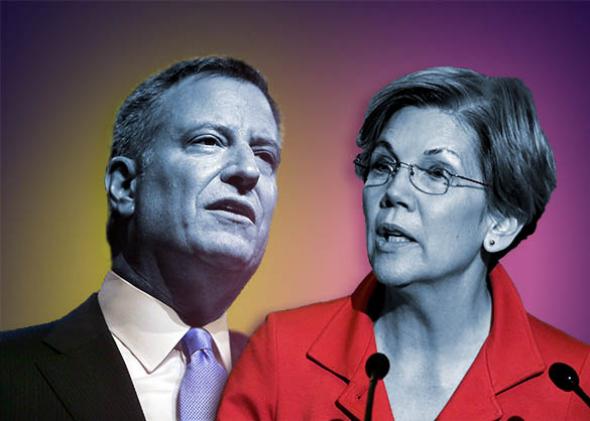

It helps, however, to have an ally. And the Roosevelt Institute has two in the form of Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio. Both spoke at the Tuesday event for the new report, urging Democrats—and Republicans, for that matter—to rethink their economic assumptions. “This country is in real trouble. The game is rigged and we are running out of time,” Warren said. “We cannot continue to run this country for the top 10 percent.” De Blasio touted his agenda in New York City—including universal pre-K and paid sick time for all workers—but urged national action. “We in New York are doing all we can, but we cannot complete the mission without fundamental change in federal policy,” he said. “There needs to be not only new debate in this country, but there needs to be a movement that will carry these ideas forward.”

To that end, de Blasio took to the Capitol steps Tuesday afternoon to unveil his “Progressive Agenda to Combat Inequality,” a deliberate echo to the 1994 “Contract With America” of Newt Gingrich and the congressional GOP. “These 13 progressive ideas,” he said, “will make an enormous difference for families all over this country, for everyday Americans.” Among the proposals are a minimum wage increase to $15 an hour, national paid sick and family leave, subsidized child care, and “closing the loopholes that allow CEOs, hedge fund managers, and billionaires to avoid paying their fair share in taxes.”

There’s no doubt Clinton will adopt this language—to an extent, she already has. But will she adopt the policies? Will she go beyond the agenda for redistribution to embrace structural change of the American economy?

The answer to this question depends on power. Is the left strong enough to budge Clinton from her ground in the corporate center of the Democratic Party? It’s too early to say—the fight has just begun—but there are signs. Hours after the Roosevelt Institute unveiled its package, the Senate held a cloture vote for a bill that would give President Obama “accelerated power to complete a major trade accord with Asia.” On this, Warren has been a strong opponent, denouncing the bill—and the accord itself—as a giveaway to corporate America. The vote failed. Warren peeled away enough Democrats to block cloture and continue debate, a blow to the president’s standing.

If this is a fluke, then Clinton can resist the calls from her left. But if it’s a sign of the times, then liberals can look forward to a Clinton campaign that sounds a lot like them.