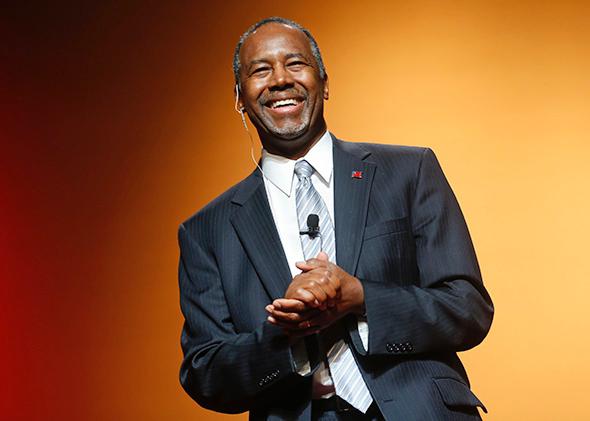

As Ben Carson begins his run for the 2016 Republican nomination—he officially announced his campaign on Monday at a music hall in Detroit—it’s easy to compare him with Herman Cain, the last black American to play presidential politics in the GOP. But other than race, the two men are incomparable. Cain, a businessman and radio host, was a showman—a personality whose flamboyant defense of the Tea Party fueled a quick rise to conservative stardom and whose attacks on President Obama carried a racial comparison. The media, he said during his campaign, “Are … scared that a real black man may run against Barack Obama.”

Carson is far from exuberant—he speaks in calm, even tones—and joins the political stage after a long career in medicine and as a motivational speaker. A famed pediatric neurosurgeon, Carson is an icon in the black community. His book Gifted Hands—the story of his rise from inner-city Detroit to the pinnacle of his field—made its way to countless black kids in countless black homes. “Carson is a great American success story,” writes Joel Anderson for BuzzFeed, “a rags-to-riches hero who embodied achievement against long odds. His achievement turned him into an icon of black triumph, a Horatio Alger figure in hospital scrubs.”

But while his career was made in hospital wards and inner-city schools, his recent fame comes from his address at the 2013 National Prayer Breakfast, where he criticized Obamacare and offered his own alternative for health care reform. From there, he became a conservative celebrity, so famous that by the end of the year, supporters had founded a political action committee to draft Carson into the presidential race.

Carson’s announcement speech was light on substance, but it’s clear he doesn’t stray far from the rest of the Republican pack. He’s opposed to Obamacare, of course; called for an end to social programs that “create dependency”; and told supporters, “It’s time to rise up and take government back.”

With that said, there is one important difference between Carson’s rhetoric and that from the rest of the presidential field: It’s in the paranoid style. Throughout his speech, Carson made reference to the assorted conspiracies of the far right. People are afraid to speak up, he said, because the “IRS might audit them.” The government, he continues, just wants you to “keep your mouth shut.” Likewise, he says, we can’t trust unemployment statistics because, he claimed, “You can make the unemployment rate anything you want it to be.”

If you go beyond his presidential announcement to look at his political rhetoric during the past year, you see a similar touch of the paranoid. In one interview, he warned that anarchy from “this pathway we are going down” could lead to the 2016 election being called off, as Obama declares “martial law.” In another, he accused Obama of using immigration to bring in new voters who will be “dependent on government.” He’s compared America under Obama to Nazi Germany, and in a speech at the 2013 Values Voter Summit, he called Obamacare the “worst thing that has happened in this nation since slavery.”

It’s this paranoid approach to conservative politics that separates Carson from Herman Cain or Allen West or any of the other black Republicans who have come to fame in the Obama era. Indeed, if Carson has fellow travelers, it’s conservative provocateurs like Glenn Beck and right-wing politicians like Michele Bachmann or Sarah Palin. Like Carson, their styles are defined by conspiratorial thinking, and like Carson, they largely appeal to the older, whiter, and most conservative voters of the Republican Party.

Can Carson turn this paranoia into votes? Probably. If he makes it to the Iowa primaries, he’ll almost certainly find support from a portion of the electorate. But there’s no chance that he’ll go beyond a modest showing with social conservatives to win a contest or even the nomination. At most, he’ll harm a more mainstream Republican, like Sen. Ted Cruz, who needs to win as many voters on the right as possible. And after that? The former hero to black Americans will likely fade from view, as another fringe candidate running another vanity campaign.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the 2016 campaign.