If Bill Clinton had a chief political goal in his two terms as president, it was to win working-class whites and restore the Democratic Party as the home for their concerns. To that end, Clinton and his allies were enthusiastic supporters of legislation such as the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, and the Defense of Marriage Act of 1996—laws that spoke to the cultural concerns of lower-income whites.

Clinton didn’t succeed in luring working-class whites back, but he stopped the bleeding, strengthening Democrats in Rust Belt and mid-Atlantic states, where they were crucial. And while this wouldn’t save Al Gore in his bid for the presidency, it would keep Democrats competitive in House and Senate races and contribute to their huge wins in the 2006 midterm elections.

Now the picture is different. Since Barack Obama’s election in 2008, working-class whites—and whites overall—have left the Democratic Party in droves. At the same time, the party has moved to the left, pushed by an Obama-led coalition of young people, minorities, and socially liberal whites. One result is that, under a more liberal Democratic president, those Clinton-era policies have come under sustained assault. Before the Supreme Court struck its key provision, the Defense of Marriage Act was all but abandoned by the Obama administration, part of the rapid march toward broad acceptance of same-sex marriage. Welfare reform is still law, and the crime bill is still on the books, but as with DOMA, a new generation of liberals has challenged the underpinnings of both, with louder calls for state support of families and children and greater skepticism of the criminal justice system.

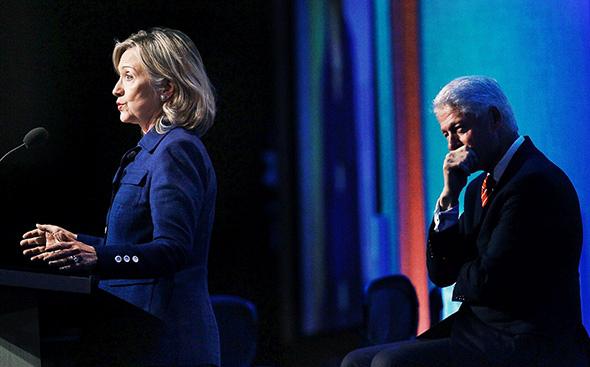

The fact of this new coalition puts Hillary Clinton, who seeks to succeed Obama on her own merits even as she’s indelibly tied to the first Clinton presidency, in a difficult place. Her task is to reassemble and re-energize Obama’s coalition, while also winning whites who may have left the party during Obama’s tenure, and even moving some whites (namely, white women) to the Democratic column.

But here’s the challenge: To do the former—and build Obama-esque enthusiasm among college students, black Americans, Latinos, and educated whites—Hillary may have to stand against the policies of her husband’s administration.

We’ve already seen this in small doses. On Tuesday, during a campaign stop in New Hampshire, Clinton met questions on an international trade deal—the Trans-Pacific Partnership—with skepticism. “We need to build things, too,” she said, positioning herself—if slightly—with labor unions who oppose the deal, and echoing an earlier statement from her campaign. “[Clinton] will be watching closely to see what is being done to crack down on currency manipulation, improve labor rights, protect the environment and health, promote transparency, and open new opportunities for our small businesses to export overseas,” said an aide.

Likewise, Clinton has “evolved” on same-sex marriage, endorsing marriage equality in 2013 and—more recently—calling on the Supreme Court to “come down on the side of same-sex couples being guaranteed that constitutional right.”

But these are easy lifts. Bill Clinton campaigned as a pro-labor candidate—even as he oversaw labor’s decline—and Hillary Clinton did the same in her 2008 campaign, running as a populist champion for union workers and others outside of the “wine-track” Obama coalition. And at this point in American politics, it’s the most painless thing in the world for a Democratic politician to support same-sex marriage. To that point, Bill Clinton has repudiated the law, calling it “discriminatory” and a “vestige” of a less free society.

Harder are moves on welfare and crime, which still pack a punch in political life, even as the latter falls in salience, especially compared with the 1990s. On welfare, the upside for mobilization is straightforward. In the last three years, a growing group of liberals—from politicians to bloggers—has called for increasing a range of federal benefits. Some want higher Social Security benefits as a response to a looming retirement crisis. Others want greater federal funds for child care or college education, and others still want the government to strengthen key safety net programs. In terms of priorities, this is a sharp turn from Bill Clinton’s administration, where the goal was reducing these programs or finding ways to make them more market-friendly. And if Hillary Clinton were to endorse them—and promise to expand public benefits—she would be making a real break from her husband’s presidency.

The same is even truer of crime. After years of declining crime rates and action from anti-incarceration activists, there’s growing momentum among Democrats and Republicans for criminal justice reform, all aimed at shrinking the prison population after decades of growth. This has become even more acute in the last year, as police shootings in New York, Ohio, and Missouri sparked a national movement for police reform among young black Americans. More than once, Clinton has voiced support for the activists, declaring, “Yes, black lives matter,” at an event last December. But she hasn’t taken a position on the substantive questions of criminal justice reform, from drug policy to federal sentencing. We don’t know how she would respond if asked to answer for Bill Clinton’s punitive criminal justice policies, which expanded the war on drugs and contributed to mass incarceration.

With that said, a promise to reject those policies—and to move back from the Clinton-era status quo—might appeal to black Americans whose communities have been harmed by mass incarceration. Indeed, it might even be the ingredient that helps Clinton energize black voters and engage a vital part of the Obama coalition. In which case, would she reject that part of her husband’s legacy?

If Hillary’s overarching political task is capturing the Obama coalition while distinguishing herself from him and Bill, the obvious answer to that question is yes, she must. A Hillary Clinton who ran as a political corrective to both presidencies—who refused to pander to social conservatives or bend to Republicans in Congress—might preclude liberal challengers and do well in the general election.

But there’s a downside. A Hillary Clinton who did that—who touted the liberal line on crime and social spending and other areas—would continue the political story of Obama’s presidency; not of shaping the new Democratic coalition, but of ending the old one her husband tried to rebuild.