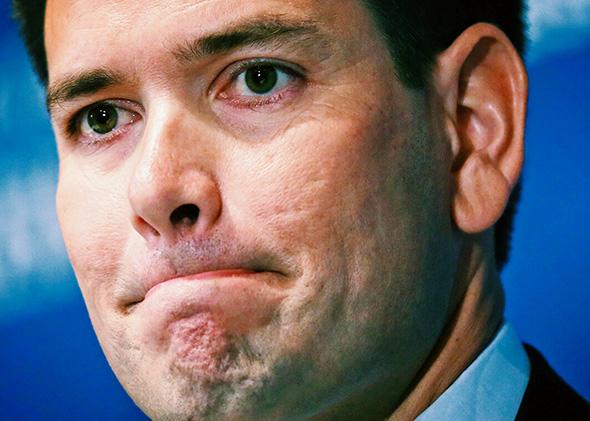

On Monday, in Miami, Sen. Marco Rubio announced his campaign for the Republican presidential nomination.

The Florida senator finds himself in an unusual position. Unlike Sens. Ted Cruz or Rand Paul—two factional candidates with roots in the far-right—he has a decent shot at success; he’s hired top-notch political talent and has solid support among major donors. But unlike Gov. Scott Walker or Jeb Bush, he’s no one’s first choice.

Instead, he’s everyone’s second choice, with clear advantages—strong speaking skills, a fantastic biography, an ambitious agenda, and a flair for retail politics—and real weaknesses, namely, a modest record in the Senate. He’s acceptable to almost everyone in the GOP—56 percent of Republican voters say they could vote for him—but he’s no one’s favorite: Just 5.4 percent list him as a top choice for the nomination. More so than most, Rubio is a serious and viable candidate for the Republican presidential ticket. But save a catastrophe in both the Bush and Walker camps, it’s hard to see how he has a path to the prize.

In fairness, you could have said the same for a certain Illinois senator in 2007, as he faced the Clinton machine and a former vice presidential candidate. But while Barack Obama also lacked any major accomplishments, he also lacked any major failures or concrete liabilities. Rubio isn’t so lucky. His introduction to the national public—his 2013 State of the Union response—was somewhere between a gaffe and a disaster, and his attempt to play conservative reformer—a yearlong push for immigration reform—ended in failure, as grassroots Republicans rejected his deal on citizenship and border security.

The next year, Rubio recalibrated. Among the first major Republicans to endorse Joni Ernst in her Iowa Senate bid, he stumped for her campaign and supported her in a tough Republican primary, earning goodwill with conservative activists in the state. He backed down on immigration reform—taking the mainstream GOP position of no “amnesty” (“[Y]ou don’t have a right to illegally immigrate into the United States”), proposed a new expansion to the Earned Income Tax Credit, and joined with Utah Sen. Mike Lee to produce a tax reform plan that aims for the Republican sweet spot of affluent families and large business owners with large, regressive tax cuts.

Now, Rubio is in decent shape. With few outright enemies in the Republican Party, he’s as close to a potential consensus candidate as you can imagine. His problem is he’s not alone. The Florida senator is a fine candidate, but depending on your place in the GOP, there are potentially better options.

If you’re a conservative who wants consensus and a more inclusive message, you have Jeb Bush, who melds Rubio’s potential appeal to Latino voters (his wife is Mexican, and he speaks fluent Spanish) with executive experience, fundraising prowess, and the all the benefits (and burdens) of the Bush name.

Likewise, if you want a more aggressive choice—someone with the chops it takes to beat Democrats and advance a conservative agenda—you have Walker, the right-wing, more grassroots alternative to Bush, who has some of Rubio’s youth—he’s just six years older than the junior senator from Florida—but with much more experience. If you’re a conservative evangelical eager for a champion, there’s Cruz (and potentially Mike Huckabee), and if you want a more libertarian choice, there’s Paul. Rubio may appeal to every base, but every base is already covered.

His only hope is for those candidates—and Bush and Walker in particular—to tear themselves apart. For them to wound each other, make fatal mistakes, and eventually open the space for a viable alternative. It’s a version of Sen. John McCain’s strategy in 2008, and it’s Rubio’s best chance for the nomination. It’s also unlikely, and even if it happened, he would have to pounce and take the moment as soon as it appeared, which—as evidenced by the long-list of almost candidates and one-time hopefuls—is incredibly difficult.

But if there’s anything Rubio excels at, it’s precisely that. Whether it’s a shot for comprehensive immigration reform or a sense that Republicans are looking for more than a small-ball agenda, Rubio knows when to seize the moment and run. It’s why he’s already in the White House game, just four years after stepping on the national stage; like Obama before him, Rubio knows that the best time to run for president is always now. Will he win the Republican nomination? Probably not. But a lot of politics is about unlikely bets, and given his position in the Republican Party, Rubio is smart to make this one.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of Marco Rubio and the 2016 campaign.