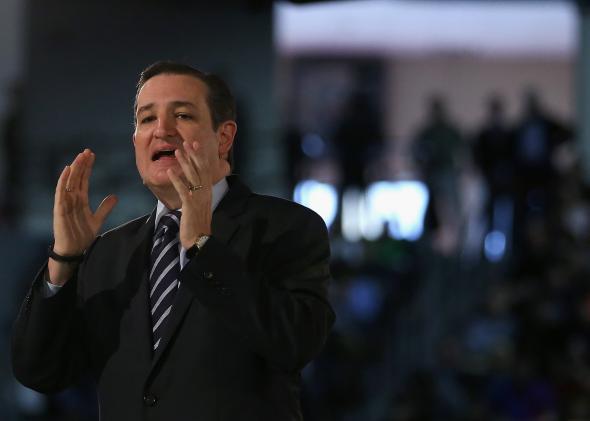

Bombastic, theatrical, and eager to make a splash, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz was a presidential hopeful from the moment he stepped on the Senate floor two years ago. But on Monday, at Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia, he finally dropped the pretense and made it official: Cruzapalooza begins now.

Because Cruz is the first to announce his candidacy, he’ll get a serious hearing in national media. He’ll attract a lot of news and win a bump in the polls. But we shouldn’t pretend that his is a serious campaign with a shot at success. It isn’t. At best, Cruz will win a Fox News contract. He won’t win the Republican nomination, and he’ll never be president of the United States.

In fairness to Cruz, there’s a logic to his campaign that makes sense. In the last two Republican nomination fights, a right-wing base of social conservatives has vied against a more moderate (or at least more pragmatic) collection of fiscal conservatives, small-business owners, foreign policy experts, and financial elites. And while the two sides overlap—and the differences are often more affect than substance—the divide is real.

The former group, social conservatives, tends to want religious candidates who prioritize public morality (see: abortion), support traditional ideas of marriage and family structure, and oppose mass immigration as an attack on the fabric of American life. By contrast, the latter group—reflecting its business concerns—tends to downplay social conservatism and is often more open to immigration, free-trade deals, and certain kinds of government intervention (see: Medicare Part D).

As the foot soldiers, social cons have the numbers in the Republican Party: They knock on doors, make phone calls, and give hundreds of thousands of small donations that fuel a whole galaxy of campaigns and organizations. But in the last two election cycles, this strength in numbers hasn’t overcome the strength of influence possessed by the “moderates.” Part of this is resources. Even when he stumbled, Mitt Romney had the cash and staff he needed to survive into the next contest. He could withstand the blows in the Southeast and the Midwest and power through to favorable terrain. By contrast, the social conservative candidate of 2008, Mike Huckabee, just didn’t have the money to run a national race. Even with momentum, he was still doomed.

But the other obstacle was the sheer number of base-driven candidates. For social conservatives, the 2012 primary was a clown car. Six candidates—Ron Paul, Newt Gingrich, Rick Santorum, Rick Perry, Michele Bachmann, and briefly, Herman Cain—vied for the same votes. Against them, on the other side, were Romney and Jon Huntsman. By the time the field had narrowed, following the initial primaries in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Florida, there was one “establishment” candidate against a handful of social conservatives. In that environment, Romney didn’t have to win a majority—he just had to keep a sizable plurality.

If you were an ambitious Tea Party Senate candidate looking at the fallout, you might conclude that the right approach for an “outsider” campaign is to ignore the establishment and try to bring base voters under one standard. If you can lead social conservatives in an undivided charge against the establishment candidate, then you could win. And if the “establishment” is actually a series of divided establishments with multiple candidates—Jeb Bush, Scott Walker, Chris Christie, and Marco Rubio—then you might even have the advantage.

That is the Cruz plan—to rally social conservatives behind one banner. It’s why he announced first, and it’s why he announced his campaign for small government and traditional values—“Instead of a federal government that works to undermine our values, imagine a federal government that works to defend the sanctity of human life and to uphold the sacrament of marriage”—at Liberty University, the brainchild and legacy of the late Rev. Jerry Falwell, one of the most influential evangelical leaders of the past 40 years. (It’s a bit ironic for the anti-government Cruz that Liberty is among the top recipients of federal student aid in Virginia.)

Not only is Cruz trying to pre-empt his immediate competitors—Bobby Jindal, Mike Huckabee, Rand Paul, and Santorum—he’s trying to lay his stake as the candidate for social conservatives. As gambits go, it’s not bad. But it’s not going to work. Yes, the Texas senator has a few good cards in his hand. He’s a strong rhetorician, with the virtual adoration of the Tea Party and other parts of the conservative base. He has a national profile and he’s comfortable with the spotlight of the national stage. But then there are the problems, the Kaiju-sized, career-crushing problems.

On high-profile issues like health care and immigration, it’s tough to say that Cruz is more extreme than other Republicans. The distance between him and someone like Bush is fairly small. But if we look at his donors, his public statements, and his voting record, it’s clear that Cruz is among the most extreme candidates to ever run for the Republican nomination, a far cry from the kinds of people the GOP tends to nominate.

Just as important is his persona. Cruz is an uncompromising politician who disdains his opponents and abhors pragmatism. He antagonizes his colleagues—Republican and Democrat—and would rather lose a quixotic fight against an established law than claim a small victory, even when the crusade is a disaster.

For much of the Republican base, all of this makes him the hero America needs and the one it deserves. To the vast constellation of Republican lawmakers, activists, intellectuals, and party operatives, it makes him a pariah. He’s isolated in the Senate and loathed in influential parts of conservative media. The party’s machinery isn’t on his side, and if party support is the best guide to who wins, then Cruz is dead on arrival.

Many liberals see the Republican Party as gripped by the passions of religious extremists and right-wing lunatics. And if that’s true, then Cruz is a favorite for the nomination. But it’s not.

For as much as the GOP is ideologically conservative, it’s also—like every iteration of America’s core political parties—a diverse collection of interests and factions with competing concerns. Some of them fit the liberal bill. Others don’t. But they’re united by a common aim: the White House. And unless the Republican Party wants another four (or eight) years outside of the Oval Office, it’s not going to nominate someone like Ted Cruz.