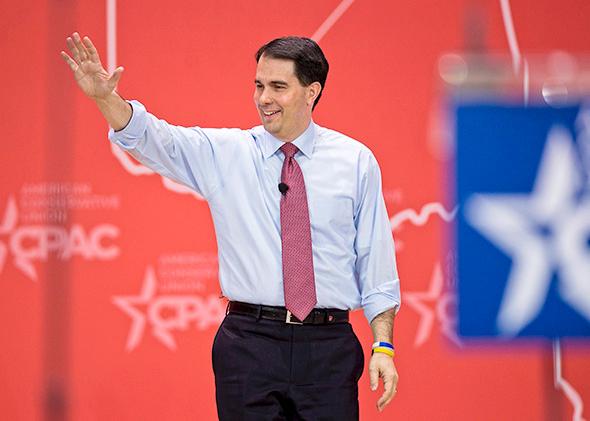

MADISON, Wisconsin—Scott Walker loves the haters. In recent years as Wisconsin has moved further to the right, the mild-mannered preacher’s son has become in the eyes of his opponents an icon of all that is evil—and he seems to relish it. On the stump, the governor is fond of talking up the fact that he’s “the No. 1 target in America of the labor unions and many others on the left,” and the hecklers that seem willing to follow him to the ends of the Earth give him a chance to flex his conservative muscles. They feed the perception that in Wisconsin, it was Walker against the world, and Walker won.

Next week Gov. Walker is expected to sign right-to-work legislation that will burnish his reputation as a bold fighter who stood against the hordes and remains unvanquished. But that image elides an important, perhaps crucial, fact about his record as a reformer: Walker is the chief beneficiary of a state Legislature that has demonstrated a boundless appetite for the kind of controversial, union-crunching attacks that have made the governor a conservative superhero. Without the Wisconsin state Legislature, Walker would just be a skinny Chris Christie.

This all starts, naturally, in 2010. You could argue that the Tea Party made greater gains in Wisconsin than in any other state in the country. Democrats lost control of the governorship, incumbent Democratic Sen. Russ Feingold lost his Senate race to upstart businessman Ron Johnson, and the GOP netted two House seats. And, most importantly, Democrats lost hold of the state Assembly and the state Senate. In 2008, Obama won Wisconsin by 14 points and Democrats dominated state politics. Two years later, Badger State Democrats were eviscerated.

Republicans are great at winning governorships in blue states. Walker is one of a host of state executives whose conservative policy goals belie the fact that his constituents consistently vote for Democratic presidential nominees. (There is Gov. Charlie Baker in Massachusetts, Gov. Bruce Rauner in Illinois, Gov. Susana Martinez in New Mexico, and Gov. Paul LePage in Maine, just to name a few.) Republican governors helming blue states is nothing new. But of all these Republican state leaders, Walker is probably the one with the most ideologically simpatico legislature.

National political pundits and election watchers often forget that state legislatures exist. But the Wisconsin Legislature has midwifed Walker’s national political prominence. Walker has stood against those that he calls “big government special interests,” but thanks to the Republicans that roared into the statehouse in 2010, he’s never stood alone.

In the case of the right-to-work legislation that the governor plans to sign on Monday, the state Legislature is arguably to his right. In fact, Walker initially expressed reservations about the new law.

“As I said before the election and have said repeatedly over the last few years, I just think right-to-work legislation right now, as well as reopening Act 10 to make any other adjustments, would be a distraction from the work that we’re trying to do,” the governor told reporters a few weeks after his re-election in November, per Wisconsin Public Radio.

But Republican state representatives didn’t share Walker’s concerns. Rep. Chris Kapenga told reporters the same week that he planned to introduce right-to-work legislation that would keep businesses from making it a condition of employment that their employees pay union dues.

Speaking with Slate, Kapenga said moving forward on the right-to- work law seemed like an obvious next step, as Republicans saw their majorities in both chambers grow in the last midterm elections.

“We just feel politically that voters have said, we like what you guys have done and we would like you to keep doing what you’re doing,” he said.

“This really has been driven by the Legislature,” he added.

Myranda Tanck, communications director for the state Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald, agreed the timing was perfect. After the November elections, the Republicans’ majority in the state Senate grew and became more conservative, and members were agitating for legislation that would take on private sector unions the same way Act 10 had taken on those in the public sector.

“It would be difficult to wait a couple years on this,” Tanck said.

And the midterm election wasn’t the only signal that the time was ripe. In February, conservatives looking to tussle with unions saw another win: Businessman Duey Stroebel, who had made support for right-to-work legislation a central part of his campaign, won a special-election Republican primary to fill a state Senate seat.

The Wisconsin Senate will vote to pass the new right-to-work bill either late Thursday or early Friday morning, and then the legislation will head for the governor’s desk where Walker will sign his name and add another item to his list of conservative wins.

Collin Roth, the managing editor of Right Wisconsin, said Walker will likely get more credit for this victory than he’ll deserve. “It’s no secret that the Legislature, particularly Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald, did all the heavy lifting on it,” Roth said.

But no one will remember that in Iowa.

None of this is to suggest that the Legislature has been in the driver’s seat for Walker’s whole governorship; the Act 10 legislation, which Walker signed in 2011 and which kicked off the massive protests that made him a hero to national conservatives, was his baby. But without having a statehouse full of allies, it would have been impossible for Walker to distinguish himself from the growing field of potential 2016 contenders.

Republican governors in blue states are typically hamstrung by their legislatures. Walker’s Legislature, to his great fortune, has propelled him. He has become the public face of a state government that is predominantly and combatively conservative. Walker’s success is an important reminder that hundreds of tiny, inexpensive state legislative elections that get zero national media attention can be the difference between being a nobody governor with a rinky-dink profile and being within spitting distance of your party’s presidential nomination.