Fifty years ago on March 7, civil rights activists John Lewis and the Rev. Hosea Williams led 600 people on a march from Selma, Alabama, to the capitol in Montgomery. Stopped by a gang of state police and white civilians on the Edmund Pettus Bridge outside of Selma, they were attacked in a vicious display of white supremacist violence. Besieged by tear gas, whips, nightsticks, and other makeshift weapons, they were injured, bloodied—dozens required care and 17, including Lewis, were hospitalized—and pushed back into town. Recorded by national media and broadcast to the world, these events would galvanize thousands of Americans, inspire a larger (and successful) march to Montgomery, and lead President Lyndon Johnson to commit to and push a voting rights act that would stand as the high-water mark of civil rights movement.

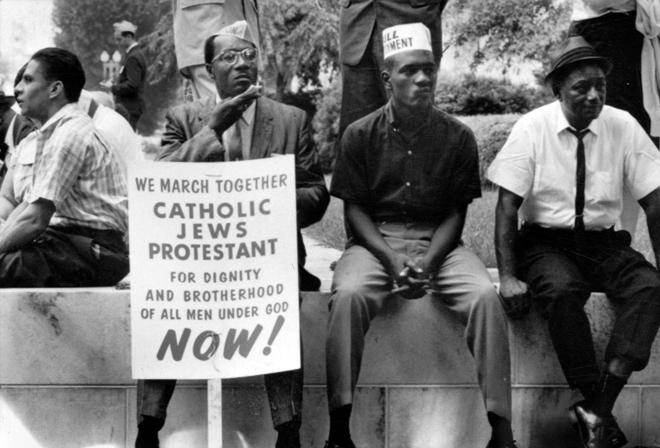

Now, in commemoration of “Bloody Sunday,” tens of thousands of Americans have converged on modern-day Selma, where they will memorialize and celebrate the great racial progress of the past half-century. Unfortunately, this happens at a time of terrible retrenchment, as a host of forces pushes back against those hard-fought wins. If the 1960s were a Second Reconstruction—a second attempt to fulfill the promise of emancipation—then our present period is a second Redemption, where a powerful movement attempts to reverse gains and dismantle our fragile efforts at racial equality.

Most Americans have a vague sense of Reconstruction—often, and unfortunately, informed by D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation—but few are aware of “Redemption,” which roughly encompassed the late 1870s to the end of the 19th century. It was the antithesis to the nascent biracial democracy of Reconstruction, where blacks enjoyed extensive political power and worked in concert with sympathetic whites to build and reform a broken South. “Public schools, hospitals, penitentiaries, and asylums for orphans and the insane were established for the first time or received increased funding. South Carolina funded medical care for poor citizens, and Alabama provided free legal counsel for indigent defendants,” writes Eric Foner of Republican Reconstruction governments. Black and white lawmakers provided food for the poor, made appropriations for schools and social welfare, pushed compulsory education, and even tried to regulate private markets and insurance companies.

Courtesy of AFP/Getty Images

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Some changes stuck and the most important one—emancipation—endured. But a decade of white violence and terrorism took its toll, and by the presidential election of 1876, recalcitrant rebels and supportive whites had seized control in much of the former Confederacy. It was in that environment that Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes promised “home rule” for the South, a new status quo in which the federal government would turn a blind eye to the white South. Hayes won a highly contested election, and as president, he gave white “Redeemers” free rein in their states, nearly unchallenged by federal troops or the voters they protected.

Far from a unified group, the Redeemers—whose ranks included secessionist Democrats, old planters, Confederate veterans, and young modernists—shared a commitment to reducing black political power and, as Foner writes, “reshaping the South’s legal system in the interests of labor control and racial subordination.” In most states where they won power, they replaced Reconstruction constitutions with new documents limiting the scope and expense of government. “Redeemer constitutions,” explains Foner, “reduced the salaries of state officials, limited the length of legislative sessions, slashed state and local property taxes, curtailed the government’s authority to incur financial obligations … and repudiated, wholly or in part, Reconstruction state debts. Public aid to railroads and other corporations was prohibited, and several states abolished their central boards of education.”

Redeemers slashed state budgets—gutting the nascent welfare states of Reconstruction governance—and all but ended taxes on land and large estates, replacing them with new levies on machinery and other items used on plantations. “Laborers, tenants, and small farmers paid taxes on virtually everything they owned—tools, mules, even furniture—while many planters had thousands of dollars in property excluded,” notes Foner. In states like Florida—where one governor, George F. Drew, advised lawmakers to “spend nothing unless absolutely necessary”—Redeemer governments leveled everything established by ex–black lawmakers. Redeemers closed hospitals, defunded state colleges, and dismantled public education systems.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

And to bolster these moves, they took care to curtail black political participation with either violence or legislation. In place of property taxes, governments levied poll taxes and other fees. In this, Redeemers had help from the federal courts, which were increasingly skeptical of race-conscious policy. In 1883, the Supreme Court overturned the Civil Rights Act of 1875, denying that the 14th Amendment prohibited private discrimination in public accommodations and declaring that “there must be some stage” where blacks cease “to be the special favorite of the laws.”

What’s striking here is how familiar this sounds, and how Redemption is echoed in the politics of the past 10 years. Then as now, the federal courts are increasingly hostile to race-conscious legislation. In 2007, with Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, the Supreme Court struck down voluntary integration efforts in an opinion punctuated by Chief Justice John Roberts’ declaration that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” In 2013, with Shelby County v. Holder, the same court struck down the preclearance provision of the Voting Rights Act, which required federal supervision in states with a history of voting discrimination.

Most recently, with Schuette v. BAMN, the court allowed voters to block affirmative action through a state constitutional amendment. And this year, following its judgment on these cases, it is expected to strike down “disparate impact,” a way of addressing stark racial disparities without the burden of proving explicit discrimination. It’s a vital piece of the civil rights arsenal—a weapon against housing discrimination and police abuse. That the Department of Justice has a case against the Ferguson Police Department in Missouri is a testament to its power; the fact of huge disparities in arrests and other police treatment was enough to justify federal action.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The Redemption parallel extends to the states as well. While the 2010 elections brought a wave of reactionary lawmakers to power throughout the country, this was especially the case in the South, where the last white Democrats fell to their Republican opponents, leaving a racially polarized politics of white Republicans and black Democrats. In short order, they imposed new voting restrictions and other laws meant to limit the franchise through obstacles and reduced access. Since 2011, more than half of states in the country have introduced or passed laws making it harder to vote, with the harshest ones in states like North Carolina, Texas, Georgia, and Wisconsin. What makes this worse is the extent to which black Democrats in the South have little input into policymaking, a product of Democratic decline and extreme polarization.

The most sweeping changes after 2010 were at the level of economic policy. In Kansas, Louisiana, and North Carolina, lawmakers made deep cuts to corporate and state income taxes. They reduced burdens on the wealthiest residents and replaced them with new fees and sales taxes that placed the heaviest burden on the poorest residents. At the same time, they’ve slashed education budgets, reduced services, and refused federal funds for the Medicaid expansion, keeping millions of low-income people—many of them black Americans—from needed medical services.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Courtesy of AFP/Getty Images

In appearance and in effect, the program of 21st-century conservatives is remarkably similar to the one of 19th-century Redeemers. It guts civil rights laws, shrinks state spending, and limits the scope of activist government. Yes, there are important differences: The conservative movement isn’t motivated by explicit racial animus as much as it is ideology, and even in the deepest South, there’s ample room for racial minorities. But it’s undeniable that the two are connected by history.

Today’s anti-government conservatism has its roots in the antebellum politics of Sen. John C. Calhoun, was modernized in reaction to the civil rights movement, and was brought to the Republican Party by an alliance of Southern reactionaries and ideological conservatives. And while it’s been attenuated from its racial history, you see hints of the past in its practical politics: The national coalition for ideological conservatism is anchored by white Southerners while the national coalition for progressive governance is anchored by blacks.

The point of this parallel isn’t to hammer conservatives with their history—liberals have an incredibly ugly racial past as well—it’s to show that American civic life has cycles, and one of those cycles is the waxing and waning of black political power. The Civil War brought Reconstruction, which was met with powerful force by the agents of white supremacy. In turn, this was wounded—perhaps fatally—by the civil rights movement, whose gains are now waning in the face of economic turmoil and conservative ascendance.

When will black influence wax again? It’s hard to say for certain. But consider that every period of black American advancement has come in the wake of a traumatic national event: the Civil War, the Second World War, the assassination of John Kennedy, and—in the case of Obama—the Great Recession. If the pattern holds, then the night will have to get very dark before we see a brighter sun.

Courtesy of AFP/Getty Images