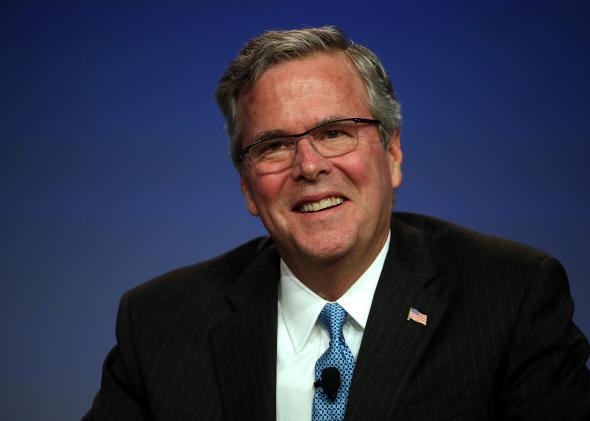

Jeb Bush has been adamant that he will not switch his positions on two issues, immigration and Common Core standards, that will generate conservative opposition in the Republican primaries. But he just made a major concession to conservatives on another issue of great importance to many of them—he came out against the U.S. Export-Import Bank. And this new position of Bush’s is not just hard to reconcile with his politics—it’s hard to reconcile with his own business career.

Over the past few years, many conservatives have seized on the Ex-Im Bank as a glaring example of crony capitalism, and they will oppose its reauthorization when it comes up in June. They say the bank, which aids exporters by guaranteeing loans for foreign buyers of U.S. products, mainly aids giants like Boeing, GE, and Caterpillar, and, under proper accounting standards, is running a 10-year deficit of $2 billion, on top of its operating costs. The bank’s supporters argue that it is helping a vast array of smaller businesses as well, and that it is essentially self-financing, at minimal cost to U.S. taxpayers. The relatively obscure institution—which was founded in 1934 and whose leadership is appointed by the president—has become a major point of contention on the right, with groups like the Club for Growth and the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity coming out against it while the traditional business lobby, led by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, supports it.

Jeb Bush would, at first blush, seem to be in the latter camp. He is a staunch internationalist and trade advocate (his first job was working for a U.S. bank in Caracas), and his views on other issues that are dividing conservatives, such as immigration and education, put him squarely on the side of the business lobby rather than with the populists. He hasn’t said much on the record about the bank in the past few years, but if he has long thought it was worthless, he had a strange way of showing it: He helped get April Foley—the wife of his high school classmate Tom Foley, a private equity manager, former ambassador to Ireland, and two-time candidate for Connecticut governor—named as vice chairman of the bank during his brother’s presidential administration.

But at this past weekend’s Club for Growth conference in Palm Beach, Florida, Bush came out against the Ex-Im Bank, to the delight of his hosts, when asked about it and other government subsidies for the private sector. “I think most of these things should be phased out,” Bush said. “Ex-Im is a smaller one. … We should find ways to lessen the contingent liability of the federal government.” Michael A. Needham, head of Heritage Action for America, the political arm of the conservative think tank now led by former Sen. Jim DeMint, told the Washington Post that he was “ecstatic” to see Bush come out against the bank. “I think he needs to address the perception people have that he’s maybe a little too tight with the business community and favoritism culture of Washington, D.C.,” Needham said.

Left unmentioned in the reception of Bush’s turn against the bank was a highly relevant fact from his own background: One of Bush’s most lucrative ventures in the business world was a partnership that relied heavily on Ex-Im financing. In 1988, as his father was in the process of moving from the vice presidency to the Oval Office, Bush branched out from the real-estate development work he’d been doing in Miami to go into business with David Eller, the head of a Deerfield Beach, Florida, manufacturer of water pumps called MWI Corp. The two men formed a partnership called Bush-El Corp. to market MWI’s pumps overseas. Some of the sales abroad were financed with the help of the Ex-Im bank, including the partnership’s most successful deal, by far: a 1992 agreement to sell pumps to Nigeria that was financed with $74.3 million from Ex-Im.

Bush has for years sought to distance himself from that deal—not because of any pejorative association with the bank, but because the deal itself came under scrutiny. A former MWI vice president, Robert Purcell, sued in 1996, alleging that the Bush-Eller partnership had diverted profits from MWI. As the Tampa Bay Times and others have reported, that suit was settled in 1998, just days before Bush was to give a sworn statement in the case and one month before he was to be on the ballot for governor. But Purcell also filed a federal whistleblower lawsuit, alleging that MWI had defrauded the government to secure Ex-Im financing by concealing that the company would provide $28 million in “commissions” to its Nigerian sales agent, Alhaji Mohammed Indimi, now an oil baron and one of the richest men in Africa. The FBI launched a criminal investigation into the Nigerian deal, which never came to anything. But the Justice Department did take up the whistleblower suit in 2002, and last year, a federal jury in Washington found MWI liable for misleading the government and not reporting that the “commissions” went toward luxury cars, mansions, and a golf expedition for Indimi.

Bush, who was not implicated in the federal trial, has for years played down his role in the Nigeria deal. He has said he had nothing to do with securing Ex-Im financing for Bush-El deals abroad. And he has said he did not receive any commission from the Nigeria deal, to avoid any perception of conflict with his father serving as president. Bush “has answered questions and refuted inaccurate claims made regarding this case multiple times. Nothing alleges any wrongdoing by Bush-El or that Bush-El was even involved in this transaction,” Bush spokeswoman Jaryn Emhof told the Tampa Bay Times in 2013. “While a marketing agent for MWI/Bush-El, he received no commissions from any sales by MWI to any countries (including Nigeria) in which Ex-Im Bank government financing was involved.”

But the fact is that Bush did make two trips to Nigeria prior to the deal’s finalization—in 1989 and 1991. On the first one, he was feted in stupendously grand fashion with a parade of 1,300 horses and tens of thousands of people lining the road to welcome the president’s son. And the Tampa Bay Times obtained a marketing video MWI made for Nigeria around the time of that first visit, in which Eller declares that his company has the “support at the highest levels of our own government,” accompanied by a picture of Eller smiling besides Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. “In fact … George Bush’s son will be coming to Nigeria with us for the inauguration of our factory,” Eller says, “and we’re very proud of that, and it shows that our government is very interested in what we’re doing in Nigeria and very supportive.”

As for Bush’s claim not to have received any commissions from deals financed by the Ex-Im bank, the fact is that his role in the partnership proved quite lucrative—he reported $648,000 in income from it until he ended it in time for his first run for governor, in 1994—and the Nigeria deal was, by far, the most successful of that stretch for MWI, amounting to four times its average annual sales. One would, essentially, have to take Bush at his word that there was no connection between his lucrative cut from the partnership and MWI’s biggest deal during that stretch. And just this past weekend, the Naples Daily News reported that former employees of MWI have asserted in recent interviews with the newspaper and in past interviews with federal authorities that Bush had earned far more than the $648,000 he reported from the partnership, and that he did in fact get a substantial cut from the Nigeria deal.

Bush’s current spokeswoman did not respond to a request for comment, and Eller has declined my request for an interview about the partnership. The Club for Growth and Chamber of Commerce also declined to comment on Bush’s turn against the Ex-Im Bank. But we can be pretty confident that we’ll be hearing more about this on the campaign trail—Nigerian horses and all—as Bush’s primary opponents make sure voters find out about his lucrative work for a partnership that relied so heavily on the Ex-Im Bank he says he now opposes.