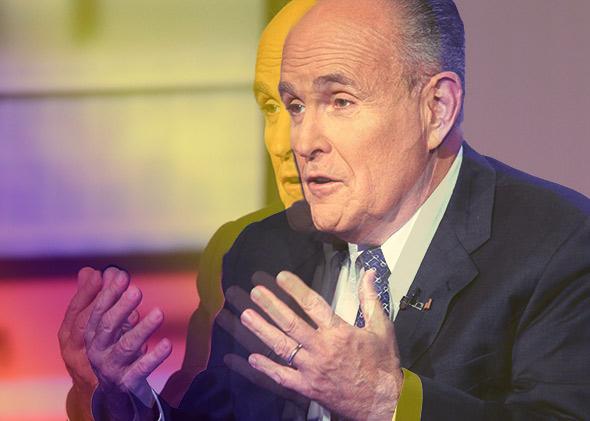

On Wednesday, Rudy Giuliani spoke to an audience of businesspeople, conservative elites, and Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker. He made news.

“The former New York mayor,” reports Politico, “directly challenged Obama’s patriotism, discussing what he called weak foreign policy decisions and questionable public remarks when confronting terrorists.”

To Politico’s credit, this is a generous summary of Giuliani’s remarks, which in reality glowed with aggrievement and disdain. “I do not believe that the president loves America. He doesn’t love you. And he doesn’t love me. He wasn’t brought up the way you were brought up and I was brought up through love of this country.”

There’s no need to litigate this charge; outside of campy political thrillers, no one devotes his or her adult life to national politics—or the presidency, for that matter—without an outsized patriotism and belief in the basic worth of the United States. But if we’re feeling generous, we can say that in the course of his rant, Giuliani touched on a real difference between Obama’s brand of national exceptionalism and the kind we tend to see from America’s presidents.

Take his remarks after the initial temper tantrum. “[W]ith all our flaws we’re the most exceptional country in the world. I’m looking for a presidential candidate who can express that, do that, and carry it out,” said the former New York mayor and onetime presidential candidate. “What country has left so many young men and women dead abroad to save other countries without taking land? This is not the colonial empire that somehow he has in his hand. I’ve never felt that from him.”

He continued: “I felt that from [George] W. [Bush]. I felt that from [Bill] Clinton. I felt that from every American president, including ones I disagreed with, including [Jimmy] Carter. I don’t feel that from President Obama.”

Crude as he is, Giuliani isn’t wrong to sense a difference between Obama and his predecessors. Previous presidents have been profuse with their praise of America’s perceived exceptionalism. And they’ve done so without question or reservation.

“More than any other people on Earth,” declared John F. Kennedy in a 1961 address to the University of Washington, “we bear burdens and accept risks unprecedented in their size and their duration, not for ourselves alone but for all who wish to be free.”

“Across the world,” said Ronald Reagan in his 1982 remarks at Kansas State University, “Americans are bringing light where there was darkness, heat where there was once only cold, and medicines where there was sickness and disease, food where there was hunger, wealth where humanity was living in squalor, and peace where there was only death and bloodshed.” Then, soaring with more outsized rhetoric: “Yes, we face awesome problems. But we can be proud of the red, white, and blue, and believe in her mission. In a world wracked by hatred, economic crisis, and political tension, America remains mankind’s best hope.”

Bill Clinton echoed his predecessors in a 1996 speech defending NATO’s intervention in Bosnia. “The fact is America remains the indispensable nation. There are times when America, and only America, can make a difference between war and peace, between freedom and repression, between hope and fear.”

Likewise, throughout his administration, George W. Bush emphasized America’s exceptionalism and expressed it in terms of its war against terror and tyranny. “Our country has accepted obligations that are difficult to fulfill and would be dishonorable to abandon. Yet because we have acted in the great liberating tradition of this nation, tens of millions have achieved their freedom,” he said in his second inaugural address. “In a world moving toward liberty, we are determined to show the meaning and promise of liberty.”

Barack Obama’s view is a little different. Compared with the visions of his predecessors, his is less triumphant and informed by a kind of civic humility. “I believe in American exceptionalism,” he told Roger Cohen of the New York Times while still just a candidate, but not one based on “our military prowess or our economic dominance.” Instead, he said, “our exceptionalism must be based on our Constitution, our principles, our values, and our ideals. We are at our best when we are speaking in a voice that captures the aspirations of people across the globe.”

As president he echoed this during a now-famous (perhaps infamous) 2009 news conference in Strasbourg, France, where he elaborated on his sense of exceptionalism. “I believe in American exceptionalism, just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.” Every nation has a sense of its unique place in the world. Even still, Obama said, there are things especially exceptional to the United States. “I think that we have a core set of values that are enshrined in our Constitution, in our body of law, in our democratic practices, in our belief in free speech and equality that, though imperfect, are exceptional.”

To be clear, Giuliani wasn’t somehow right, and to say he even made a point is to overstate the case. But it is true that Obama stands outside the norm. No, he’s not Jeremiah Wright, but he’s not Reagan either.

The obvious question is, Why? Why is Obama more circumspect than his presidential peers? Why does his praise come with a note of reservation?

The best answer, I think, lies in identity. By choice as much as birth, Obama is a black American. And black Americans, more than most, have a complicated relationship with our country. It’s our home as much as it’s been our oppressor: a place of freedom and opportunity as much as a source of violence and degradation. We’re an old American tribe, with deep roots in the land and a strong hand in the labor of the nation. But we’re often seen as other—a suspect class that just doesn’t fit.

As a president from black America, Obama carries this with him, and it comes through in his sometimes less-than-effusive vision of national greatness. He loves this country, but he also tempers his view with a nod toward the uglier parts of our history.

This isn’t the exceptionalism of the Republican Party or much of the national mainstream, and it can alienate Americans not used to a more critical eye—it’s why Mitt Romney chose “Believe in America” for his 2012 election slogan. But it is as authentically American as any other. And while Obama is far from a perfect president, I’m at least glad he’s here to give it a greater voice.