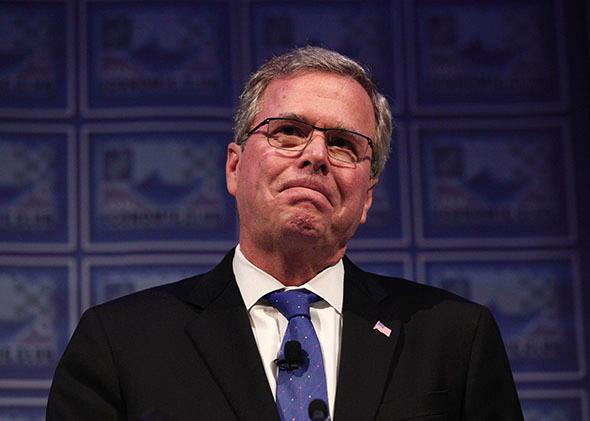

Jeb Bush enters the White House race as the son of one president and the brother of another. And it’s this, far more than his résumé, that defines his appeal to the top-shelf donors and professionals of the Republican Party. Take away the surname, and Jeb is just another George Pataki or Bob Ehrlich—an out-of-shape politician with the delusional confidence to believe he could be president.

But the public seems nervous about a dynastic candidate and a third Bush presidency, and it’s to that concern that Jeb is trying to distance himself from the two Georges. If elected president, his Bush administration wouldn’t be a sequel, a reboot, or a reimagining of earlier entries. His would be different. He would be his “own man.”

“I love my father and my brother. I admire their service to the nation and the difficult decisions they had to make,” said Bush in a Wednesday speech sponsored by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. “But I am my own man—and my views are shaped by my own thinking and own experiences.”

Yes, he’s a Bush, and yes, he’s a Republican, but Jeb Bush wants to assure voters he isn’t a Bush Republican. This is impossible. Not because of his name, but because Jeb is a mainstream Republican, and by definition this puts him a stone’s throw from his brother’s administration.

Despite the rancor and division of the last seven years, the truth is that the GOP still sits in the shadow of George W. Bush. Even the Tea Party doesn’t escape his influence; its anti-establishment rhetoric and angry denunciations of government obscure the extent to which its supporters—such as Sens. Ted Cruz of Texas and Marco Rubio of Florida—promote the basic Bush agenda of broad tax cuts, deficit spending, social conservatism, and an aggressive foreign policy.

The largest Tea Party disagreement is around immigration. Conservative anti-immigration anger is a defining fact of the present political environment and it has shoved the Republican mainstream to the right wing of the immigration debate. But beyond this, the difference between the Tea Party and the mainstream is largely affective: Tea Party Republicans drop the “compassion” of Bushism for hard-nosed opposition to social spending for the non-elderly and non-poor, and they’ve elevated intransigence to a high political principle. This isn’t insignificant, but it’s not the stuff of schisms either.

Indeed, the best illustration of the short distance between the then and now of the Republican Party is the Mitt Romney presidential campaign. “Self-deportation” aside, little Romney proposed—from tax cuts to greater investment in Iraq and Afghanistan—would have been out-of-sync with the GOP in 2004 or 2006. But this puts Jeb in a bind. If today’s mainstream is just a few steps away from the one his brother built, then the fact that he is running for president—and trying to win support from all wings of the Republican Party—means there’s no escape from the previous administration.

All of this adds a layer of irony to Jeb Bush’s Chicago speech, which moves from a statement of identity—“I’m my own man”—to a standard-issue attack on President Obama’s foreign policy as timid and unfocused. “Weakness invites war,” declared the younger Bush, promising a “liberty diplomacy” centered on “enforcing” peace and security around the globe. With a little more swagger, it could have come directly from George W. Bush.

If this wasn’t enough to undermine his claims of independence, there’s also the list of Jeb’s foreign policy advisers, which doubles as a yearbook for the GOP security establishment. Key officials from both Bush administrations are present, with a heavy roster from the previous decade of Bush policymaking: Michael Hayden (former NSA director), Tom Ridge (former secretary of homeland security), Michael Chertoff (the second secretary of Homeland Security), Porter Goss (former CIA director), Meghan O’Sullivan (former deputy national security adviser on Iraq and Afghanistan), Michael Mukasey (former attorney general), Paul Wolfowitz (former deputy secretary of defense), Stephen Hadley (former national security adviser), and James Baker (chief of staff for Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush).

In fairness, you probably shouldn’t use this as direct evidence of the next Bush’s foreign policy—to the extent they’ve joined a third Bush campaign (Team Bush III: Bush Hard With a Vengeance), it’s because they’re the most experienced foreign policy hands in the Republican Party. As the candidate of at least one establishment, it would be shocking if Jeb didn’t have support of figures from the last two Republican presidential administrations.

Which gets to an important fact of the presidential process. When we say someone is “running for the nomination,” what we mean is that he’s building consensus for his candidacy. And while it’s possible for a powerful, skilled figure to change the terms of that consensus, most candidates simply adapt their platforms and ideas to what the party wants. Anyone who represents the Republican Party in 2016, and thus the Republican mainstream, will end up selling a spin on Bushism. Jeb’s unique problem is that he can’t elide this with rhetoric.

You could say the same of Hillary Clinton vis-à-vis Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. The difference is this: Bill is among the most popular political figures in the country, and—barring disaster—Obama will finish his term more liked than his predecessor. (His approval ratings are on the steady upswing.) At best, this can help Hillary and at worst, it won’t mean anything—she’ll rise or fall of her own accord.

Between his party and his name, Jeb is too tied to his brother. And while some Republicans like the older Bush sibling, the rest of the country isn’t too keen.