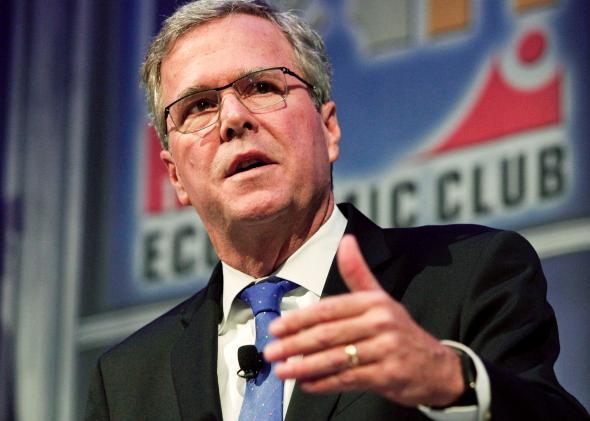

I’ve never met Jeb Bush. But this week our lives intersected in a funny way. On Wednesday, Bush addressed the Detroit Economic Club, in what many saw as a coming-out party for his nascent presidential campaign. In the wind-up to the speech, Dana Bash and Jeremy Diamond of CNN reported that Bush would offer up something called “reform conservatism,” which they described as similar to the “compassionate conservatism” of his older brother, George W. Bush. For reasons that will soon become clear, the comparison made me wince a bit. I couldn’t exactly blame Bash and Diamond for not being fully up to speed on reform conservatism, as the term is used almost exclusively by a handful of nerds. But if Jeb Bush is serious about running as a reform conservative, and if other would-be reformers, like Marco Rubio, also throw their hats into the ring, that will soon change.

Bash and Diamond aren’t the first journalists to cotton onto the existence of reform conservatism. On Tuesday, Bob Davis of the Wall Street Journal reported on the young “reformicons”—a term that brings to mind a hitherto unknown faction of Transformers—challenging the GOP establishment. (For the record, most reform conservatives favor “reformocons” over “reformicons,” so I’ll use that spelling from here on out.) According to Davis, the really distinctive thing about the reformocons is that they prefer middle-class tax cuts over the rate cuts for the rich favored by many supply-siders. Last summer, Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne offered an extended critique in Democracy Journal. For Dionne, reform conservatism is the anti–Tea Party. Whereas the Tea Party represents (in his view) “extreme opposition to government,” reformocons are (also in his view) people that the left can do business with, if only they would acknowledge how much they have in common with Barack Obama. Others have weighed in on reform conservatism, too. Rush Limbaugh, one of America’s most influential conservatives, has given it a definitive thumbs down, as have others on the right who see the reformers as RINO moderate squishes.

So what do the reformocons believe, exactly? Are they the GOP’s answer to the New Democrats, a moderate faction devoted to making their party more electable by dragging it to the center? Or are they clever marketers trying to rebrand Reaganism for the 21st century? The simplest answer is that reform conservatives are garden-variety free-market conservatives who believe that a well-designed safety net and high-quality public services are essential parts of making entrepreneurial capitalism work. This separates them from more emphatically libertarian conservatives for whom the first priority is to eliminate as many government programs as possible. Then again, this anti-government zeal tends to be more rhetorical than real. Most rank-and-file conservatives tenaciously defend old-age social insurance programs like Social Security and Medicare. Meanwhile, most conservative lawmakers who call for, say, shutting down the U.S. Department of Education routinely vote to spend on every major program it oversees. You could say that reform conservatives are just acknowledging the obvious: Government is in the business of protecting people from some of the downside risks of economic life, so we might as well get used to it. Reformocons go further than that, though, in arguing that government can do a lot of good, provided that it sticks to doing a few things well.

Instead of defending the welfare state in its current form, reformocons look at the goals of programs like Social Security and Medicare and then try to find better, fairer, more cost-effective ways of achieving them. They believe a few other things as well. To the extent possible, social programs that help those who fall on hard times should be geared toward helping them achieve economic self-sufficiency, rather than letting them become permanently dependent. The tax code should encourage savings and investment. But it should also help low-wage workers out of poverty and do more for families with children. Barriers to upward mobility, like licensing restrictions that bar access to employment opportunities or urban land-use regulations that make housing unaffordable, are suspect. Reform conservatives, like most conservatives, favor greater competition in education and health care. Yet they also insist that government has a big role to play in making sure that everyone, particularly the poor, can reap the benefits of competition.

I feel pretty confident in talking about the reformocons because I’ve been one of them from the beginning. In 2008, I co-authored Grand New Party with Ross Douthat. Oh, you haven’t heard of it? Let’s just say it never became a publishing phenomenon on the order of Fifty Shades of Grey. What it did do was give us an opportunity to talk about where the GOP had gone wrong, and why we believed the party was in for a massive defeat. While the Republican Party had long derived its electoral strength from working- and middle-class Americans, we argued that it had done a poor job of championing their economic interests, a problem that had grown particularly acute during the George W. Bush years. Douthat and I first bonded when we flipped out over how Bush, who had won re-election in part by winning over stressed-out lower-middle-class moms, pushed private Social Security accounts and comprehensive immigration reform as his top priorities in 2005. We literally thought the president had gone loco, and we became convinced that the Democrats would sweep Congress in 2006. Unfortunately, we were right.

On the surface, not much has changed since then. Yes, Republicans have done much better in midterm elections. But when Republicans gather to talk about the chief economic challenges facing the country, they tend to talk, as Jeb Bush did in Detroit, about how excessive regulation and high taxes get in the way of business owners. Though these issues are vitally important, they tend not to resonate with Americans who don’t own businesses or for whom federal taxes are a lot less burdensome than, say, their insurance premiums or their student loan debt. Compassionate conservatism, the rallying cry of George W. Bush’s 2000 campaign, rested on the premise that while working- and middle-class Americans were in fine shape, inner-city youth, less-skilled immigrants, and other people living on the margins of society needed the help of faith-based initiatives funded by Uncle Sam. During the prosperous late 1990s, when compassionate conservatism first came into being, this vision might have seemed somewhat plausible. Yet even then it should have been clear that there were far bigger problems on the horizon. The basics of a middle-class life (a paycheck that grows a bit from year to year, medical insurance you can rely on, an affordable education for your kids) were already starting to slip away for tens of millions of Americans, not just for the unfortunates deserving of our compassion. Reformocons believe that fixing what’s wrong with the American economy will take more than just tinkering around the edges.

The good news is that there is a new intellectual ferment on the right, thanks in part to the rise of reform conservatism and the Tea Party, movements that have more in common than you might think. Over the past few years, reform conservatism has grown from a small clique to a broader tendency. You’ll find reform conservatives at think tanks, like the American Enterprise Institute, and at magazines like National Review and the Weekly Standard. But you’ll also find them among younger conservatives frustrated by today’s GOP. We now have a house organ in the policy journal founded by Yuval Levin, National Affairs, and a mainstream outlet for our ideas in the form of Douthat’s New York Times column and Ramesh Ponnuru’s writing for Bloomberg View. All the while, Tea Party conservatives have been taking on the GOP establishment for its coziness with K Street and Wall Street, to the delight of reformocons who also want to shake up the Republican status quo. It’s no coincidence that you’ll often hear reformist themes from Sen. Mike Lee, the Tea Party stalwart from Utah. And on Wednesday, we also heard them from Jeb Bush—or some of them, at least.

The central theme of Bush’s speech, that government often gets in the way of Americans trying to climb the economic ladder, is an important and valuable one that has the potential to resonate not just with conservatives, but with anyone who’s had to wrestle with red tape. Bush’s emphasis on the importance of committed families was welcome, if not exactly controversial. School choice, one of Bush’s preoccupations during his two successful terms as governor of Florida, is very much a cause worth fighting for. I even applaud the sentiment behind Bush’s declaration that the U.S. shouldn’t settle for anything less than 4 percent growth a year, a target that is wildly unrealistic but not a bad thing to shoot for. My problem with the speech is that Bush was playing it safe.

Though Bush spoke movingly about the challenges facing the tens of millions of Americans who live paycheck to paycheck, he never really reckoned with the fact that America’s economic woes began long before Barack Obama became president and that the bloated government he rightly criticizes is very much a bipartisan failure. What I really wanted was for Bush to demonstrate that he understood why so many Americans had lost their faith in the Republican Party, and why he deserved their trust. He failed to do that. Instead of offering an agenda worthy of a future president, he offered compassion for those who’ve missed out on the fruits of America’s sluggish economic growth and a series of minor tweaks that are better suited to a governor or a mayor than to the next president. To be the candidate of reform, he’ll have to do better.

My reformocon homework assignment for would-be GOP presidential candidates is simple. Don’t just tell us what you’re against. Tell us what you’re for, and be specific. You don’t like Obamacare? I don’t either. Got anything cheaper that will cover at least as many people? Not a fan of stagnant wages? Neither am I. Walk me through how deregulation or corporate tax reform or a bigger tax benefit for low-wage workers might help. Think our immigration system is broken? Me too! On what basis should we choose who does and does not get to become an American? Republicans have been trying to get by on government-bashing swagger and vague, poll-tested generalities for too long. The time has come to put some meat on the bone.