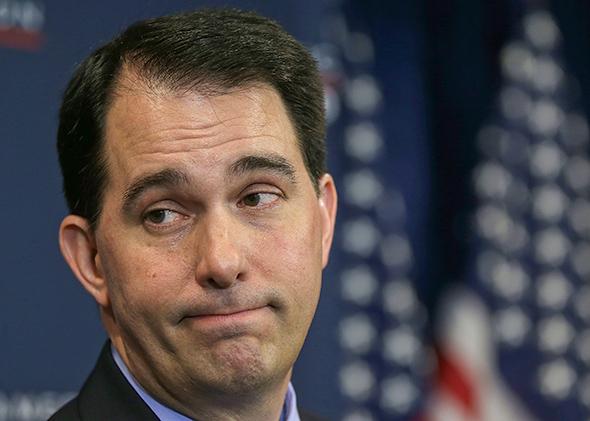

Chris Christie and Scott Walker have had some minor stumbles in recent days. When New Jersey’s governor was asked about President Obama’s statement that parents should have their children vaccinated for measles, Christie’s first reaction was to call for “balance,” seeming to weigh parental preference as much as public health. Soon after, his office issued a clarification that more forcefully advocated in favor of vaccinations. Walker, on ABC’s This Week called for an “aggressive response to ISIS,” but when the Wisconsin governor was pressed on what that meant in Syria, his response was vague.

Some may consider these disqualifying moments for two candidates auditioning for the presidency. The criticism was that Christie—who once said people who refused to evacuate during Hurricane Sandy were “stupid and selfish”—was now calling for balance in public health only to appease the big-government skeptics in his party. An aide to one of Walker’s Republican opponents said the governor’s translucent answers on ISIS showed that while he may know about public sector unions, he has no understanding of foreign policy.

But for that vast majority who might still be considering these candidates—or have yet to learn that they are even running for president—these early-round stumbles and threadbare answers should be welcomed. They offer a chance to learn something far more important about the candidate than their positions on the issues at hand. They offer us the chance to watch them learn on the job, a skill all presidents must have.

Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates was asked on Meet the Press this Sunday which quality he looked for in a presidential candidate. He said temperament, as he did a year ago when I asked him that question, but he also suggested voters should examine the people a president hires. Great presidents “never considered themselves the smartest guy in the room,” said Gates, “but they wanted the smartest people around them. And then they could take their advice, shape it based on their own instincts and their own views. So I think the kind of people that a candidate wants advising him or her is critically important.”

With both Christie and Walker, their answers were shaped more by wanting to present themselves in opposition to President Obama than they were by any informed worldview. But now both governors will presumably go to school on the subject of vaccinations and ISIS. They have to find the right people to talk to, ask the right questions, and formulate better answers. That is what a president does.

In a few months they should be asked if their views have changed in the intervening period. If campaigns took place under laboratory conditions, then candidates wouldn’t be allowed to blow off the question, saying it had been asked and answered long ago or that a past “gaffe” was a misinterpretation of their views. In their answers they would not only have to demonstrate a more considered response, but whether they have come to understand the related issues at play.

Candidates can’t be clueless on all issues obviously, but since the presidency is one surprise after another, it’s as important to know how a president learns about what he doesn’t know, as it is to find out what a president actually knows.