It has come to this: to inspire Washington to take on what everyone agrees is one of the most pressing issues of our time—tax reform—Senate Republicans scheduled Bob Packwood for a pep talk.

Wait, that Bob Packwood? Yes, that one: the moderate Republican from Oregon who was forced to resign from the Senate in 1995 amid allegations from more than a dozen women, mostly lobbyists and former staffers, that he’d made unwanted advances on them. (“He swooped down out of the blue, usually embracing a woman under the fluorescent lights of an inner office,” reported the New York Times Magazine. “ ‘I have no idea,’ one alleged victim says, ‘why this man thinks women are going to suddenly rip their clothes off.’ ”)

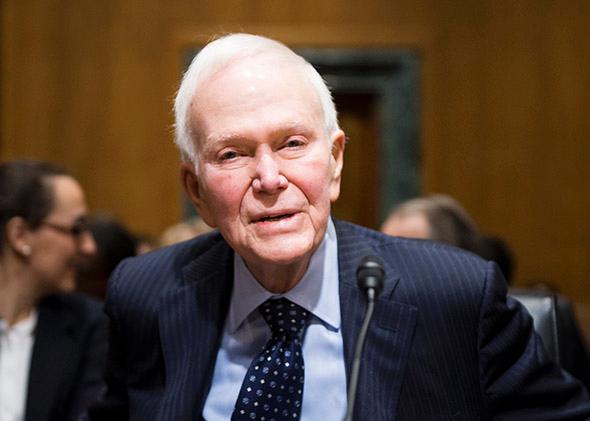

After leaving the Senate, Packwood settled into life as a health care lobbyist—as of last year, he was still pulling down $240,000 per year from his main client, a Medicaid HMO.* And there he was on Tuesday, quite spry at 82, appearing before the Senate Finance Committee, to talk about the last time that Congress managed a comprehensive tax overhaul, the Tax Reform Act of 1986. His mission: to rally members of the panel he had led at the time to take on the challenge once again.

It was a rather surreal reminder that the clubbiness of the Senate apparently knows no bounds. Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch, the Utah Republican, had many warm words for Packwood, calling him a “really great former leader” and a “great human being.” (It’s a bipartisan tendency: Just last September, Vice President Joe Biden, Packwood’s former Senate colleague, sang his praises at a women’s conference.) At one point in his testimony, Packwood fondly referred to the Senate as a “small fraternity,” an all-too-apt comparison given the nature of the allegations that had drummed him out of it.

But this jarring coziness was not the only impression left by Packwood’s return to the hallowed halls. Far from stirring the Senate’s resolve to tackle comprehensive tax reform, the hearing served only as further evidence of why progress on this issue is so unlikely. Over and over, Packwood and the witness called as his counterpart by the Democrats on the committee, former New Jersey senator and presidential candidate Bill Bradley, offered reminders of how utterly different the landscape in Congress is now than it was when they came together on the 1986 overhaul.

Yes, some of those changes are welcome—for one thing, it would be far more difficult for someone like Packwood to get away for years with such predatory behavior. But Packwood also points to another, less salutary shift on the Hill: There are precious few Republicans left who share his moderate brand of politics.

It was striking to hear him at the hearing speaking in positive terms about the 1986 reform’s emphasis on maintaining the progressivity of the tax code, by raising the tax rate on capital gains so that it would be equal with the new top rate for regular income, which was lowered from 34 to 28 percent. “We wanted to keep the same progressivity,” Packwood said. And again: “It was to make sure our progressivity was the same.” He repeatedly cited the leading role played in the negotiations by then–Treasury Secretary Jim Baker’s deputy, Richard Darman—who just a few years later would be savaged by conservatives for agreeing to a tax hike as a member of President George H.W. Bush’s administration.

At several points, Packwood lamented that to pass the final package, he had to make an “odious deal with the oilies”—senators from oil states—a complaint that one would never hear coming from Republicans today. And he openly acknowledged that many of the tax breaks for the wealthy and corporations that the package eliminated were hard to justify. “Democrats wanted to get rid of unjustifiable deductions, and Republicans were OK with that as long as you could lower the rates,” he said. “You had willingness on both sides to reach the same conclusion.”

Nothing remotely close to such symbiosis exists today. Republicans say they will engage only in tax reform that is revenue neutral, if not revenue-reducing; most Democrats are adamant that reform would need to bring in additional revenues to address rising costs like baby-boomer Medicare. Republicans say any reform should include both corporate and individual tax rates; Democrats say the focus should be on corporate tax reform alone. Potential game-changing proposals, such as using a carbon tax or gasoline tax increase to lower the payroll tax, have been shot down—just recently, the new House Ways and Means Chairman, Rep. Paul Ryan, rejected out of hand a gas tax hike.

The differences were on stark display once it came time for the senators to question Packwood and Bradley. Hatch opened by noting that tax revenues, as a share of the economy, are now a jot higher than their 50-year average, which, he said, argued against revenue-raising tax reform. Sen. Chuck Grassley, the Iowa Republican, who sat with his eyes closed for much of the testimony, roused himself to make the point about reform needing to include both corporate and individual rates. Virtually all the Republican senators who spoke blamed President Obama for not being as committed to tax reform as President Ronald Reagan had been in 1986—never mind that it was House Speaker John Boehner who scoffed at the detailed and well-received reform plan released last year by his fellow Republican, then–House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp. “Blah, blah, blah,” Boehner said when pressed about Camp’s proposals.

The ranking Democrat on the committee, Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon, a longtime tax reform enthusiast, tried to make encouraging noises, but his fellow Democrat Sen. Bill Nelson, of Florida, was doubtful. “President Reagan was pivotal at tamping down opposition among Republicans in the House,” Nelson said to Packwood. “How are you going to get President Obama to tamp down that opposition today, with the knee-jerk reaction among Republicans to just the word ‘tax’? It’s hard for me to make the transition from your era to today.”

Packwood admitted as much. “In our era, there was much more nonpartisanship in the Senate than today,” he said. “If the Republican position is, ‘no bill if there are revenue increases’ and the Democratic position is ‘no bill unless there are revenue increases,’ then you might as well spend time on … something else.” A moment later, Bradley echoed him: “If you can’t bridge that gap, spend your time doing something else.”

So why bother? One subset of the committee seemed to have decided as much going into the hearing. It was hard to miss that neither of the women on the panel, Sens. Debbie Stabenow of Michigan or Maria Cantwell of Washington, asked Packwood a single question. Though that may well have been their way of signifying what they made of his return to this “small fraternity.”

*Correction, Feb. 11, 2015: This article originally misstated how much Packwood earned from his main lobbying client last year. It was $240,000, not $240,00. (Return.)