Every state celebrates Martin Luther King Jr. Day, but not every state celebrates it the same way. In New Hampshire, King’s birthday is “Martin Luther King Jr. Civil Rights Day,” an explicit celebration of the entire civil rights movement (and a compromise with lawmakers who didn’t want a day devoted to King alone). In Idaho, it’s “Martin Luther King, Jr.–Idaho Human Rights Day,” a celebration of justice writ large. And in three states—Alabama, Arkansas, and Mississippi—MLK Day is also Robert E. Lee Day

This isn’t a different Robert E. Lee—some forgotten crusader for human equality. No, this is the Gen. Robert E. Lee who led Confederate armies in war against the United States, who defended a nation built on the “great truth” that the “negro is not equal to the white man,” and whose armies kidnapped and sold free black Americans whenever they had the opportunity.

Despite his betrayal of the Union (a stark contrast to fellow Virginian Winfield Scott, who refused to join the Confederacy) and his treatment of enslaved black Americans—as a slavedriver, he sold children and oversaw brutal punishments, including sewing brine into the wounds of returned fugitives—Lee’s popular image is of an honorable and decent man who fought well and loathed slavery. (The former is debatable and the latter is true, in that Lee thought slaveholding a burdensome occupation.)

There are three other states that commemorate the life of Lee: Georgia, Florida, and Virginia. The difference is that their celebrations are all separate from MLK Day, if only by a few days: Virginia’s Robert E. Lee Day was this past Friday.

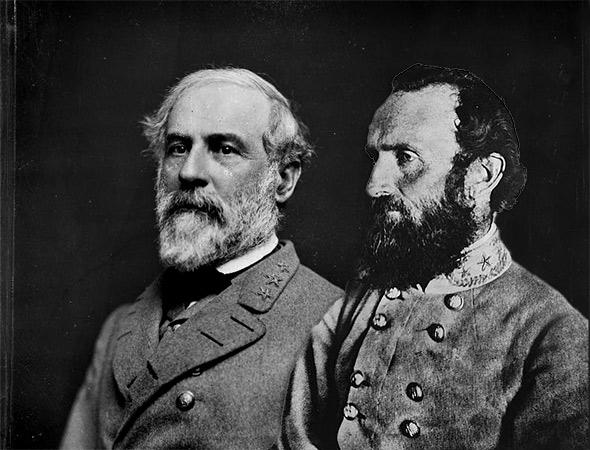

In fairness, Lee Day isn’t a recent invention. The general’s birthday falls on Jan. 19, and the first official commemoration was marked by the Virginia legislature in 1889, a decade after the end of Reconstruction and well into the period of racial regression, when Southern state legislatures dismantled efforts at biracial education, imposed Jim Crow, and turned a blind eye to anti-black terrorism. And in 1904, Robert E. Lee Day became “Lee-Jackson Day” after Virginia added Confederate Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson to the holiday.

All of this raises an obvious question: How did Lee get tangled up in our national commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement? The best answer is convenience. In states that commemorated Lee, lawmakers who approved of MLK Day didn’t want to create two holidays in January. Instead, they combined the two days. As a concept, it was a poor pairing. As a bureaucratic solution, it worked.

But over the next two decades, under pressure from civil rights groups, several states would either end their Lee commemorations or move them to a different day. In 2000, pushed by Republican Gov. Jim Gilmore, Virginia would end the state’s “Lee-Jackson-King Day” and reserve the third Monday of January for the civil rights leader.

It should be said that the “Lee” part of “Lee-King Day” is mostly downplayed in states that have the holiday. Outside of a few towns and counties, there aren’t any public events in honor of Lee’s memory. The general, a symbol of the white South—or at least, a version of it—exists in quiet tension with King, a symbol of a more modern, integrated South. Still, it’s not hard to find some commemoration of Lee, who continues to capture Southern imaginations. “If the image of Lee changes in history, the man himself did not, even in the face of the greatest provocations,” writes Paul Greenberg for the Arkansas-Democrat Gazette in its annual editorial on the life of Lee, “His victories were great, but his honor greater.”

As a Virginian, I understand the drive to praise Lee. His honor is an undeniable and worthy quality. But we shouldn’t forget what Lee fought for. Not for freedom or for liberty, but for perpetual bondage and a South that forever held its black citizens as slaves and servants. And while Lee spent the post-war period as an advocate for reconciliation, he also opposed the nascent moves toward racial egalitarianism, condemning black suffrage, even as many black leaders favored voting rights for former Confederates and the education for their children.

Indeed, if anyone should want an end to official celebrations of Lee and the Confederacy, it’s the white Southerners who hold on to this memory. The general isn’t just a totem of the Confederacy or an avatar for abstract qualities of honor and service; he’s a symbol of destructive white resistance to the opportunities of Reconstruction. If the white South had moved in a direction that opposed Lee’s values—if it had embraced the great potential that came with the end of slavery—we would have a different, and likely better, America than the one we live in.