A defining feature of the Obama era—or at least one of them—is polarization.

Voters, and especially activists, are more uncompromising than they’ve ever been. This isn’t a bad thing. Activist intensity—backed by public interest—can force action and make parties more responsive to their voters. Intensity, for example, is one reason President Obama made his executive move on immigration, and it’s one reason Republicans are trying to push back with condemnation and countermeasures. Likewise, intensity is what pushed Democrats to pass health care reform despite the huge political costs, and it’s why—nearly five years later—Republicans are still trying to repeal the law and its benefits.

But, for as much as intensity contributes to politics, we shouldn’t give short shrift to its sibling: public apathy. Apathy gets a bad rap, but when you look at its full place in the world of public policy, it’s underrated.

To be clear, apathy’s reputation isn’t undeserved. Politicians have long used voter disinterest as cover for corrupt behavior. And on issues toward which voters aren’t attentive—but interest groups are—the public can get shafted. But the same shadows that cloak the worst of our lawmakers can also shield the best of them. On issues with which the problems are severe and about which voters are indifferent, politicians have a chance to act effectively for the public good without watching their rears.

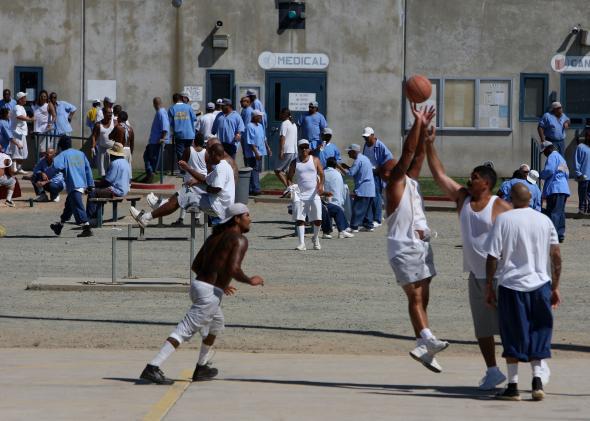

The best example is criminal justice reform. During the last decade, lawmakers across the country have pushed bold experiments in shrinking prisons and reducing incarcerated populations, unscathed by any kind of public backlash. In 2010, after two decades of ceaseless prison growth, Texas officials—supported by Gov. Rick Perry—moved to counter increasing costs of prison construction and incarceration with a new regime of treatment and mental health programs to give prosecutors and judges a third option besides jail or parole. It worked. The Texas inmate population has dropped from its peak of 173,000 in 2010 to 168,000 in 2013, without any increase in violent or property crime. Recidivism is down, and the state has saved an estimated $3 billion.

You see a similar story in Georgia, where Gov. Nathan Deal has led the state to drastically change its approach to criminal justice. In 2012, lawmakers passed reforms that gave prosecutors non-prison options for adults arrested for minor crimes, and that gave judges more options for drug offenses, with a goal of reserving prison beds for violent offenders. And in 2013 the state passed reforms that would place minor juvenile offenders in social service programs, skipping the criminal justice system entirely.

Likewise last year, Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant signed a package with a similar set of reforms, including priority prison space for violent and career offenders, alternatives to incarceration for low-level offenders, and direct efforts to improve integration and reduce recidivism. And in Congress, a burgeoning coalition of Republicans and Democrats is working to reform several areas of the criminal justice system, from mandatory minimum punishments to asset forfeiture. On Tuesday, for instance, Minnesota Rep. Keith Ellison—co-chairman of the Congressional Progressive Caucus—joined Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul in reintroducing the Fifth Amendment Integrity Restoration Act, which would limit federal, state, and local ability to seize property from criminal suspects.

These changes are long overdue. As early as 15 years ago, we knew there were diminishing returns to incarceration. The steady growth of prisons and prison populations brought few additional gains to public safety. But 15 years ago, these reforms would have been impossible. Then, crime topped the list of concerns for the public. And while most Americans still believe crime is getting worse—a persistent feature of opinion polling on the question—actual criminal victimization is at its lowest level in a generation, and crime barely registers as an issue of national concern. (To that point, Sen. Paul and Rep. Ellison held a press conference for their bill. Six reporters came to the event.)

On crime, in other words, the broad public just isn’t that interested. And as such, there isn’t a strong incentive for “tough on crime” rhetoric, crime-focused politicians, or punitive anti-crime policies. But for those on the other side of the issue—for politicians who want fewer prisons and less incarceration—there’s an opportunity to push reform without fear of attack. And slowly, lawmakers are taking it.

Thanks in part to public apathy, the country is beginning to make progress on one of our most important problems. But we shouldn’t get too optimistic. Bills against asset forfeiture or for flexibility in sentencing are like the first few boards in a game of Ms. Pac-Man—easy to clear if you know what to do. To tackle the larger problems—overcriminalization, disinvestment in prison alternatives, and robust reintegration for former offenders—you need more: more will, more skill, and more support. You also need more money beyond the savings you gain from reform. And in politics, the moment you ask for cash is the moment the public starts to pay attention.