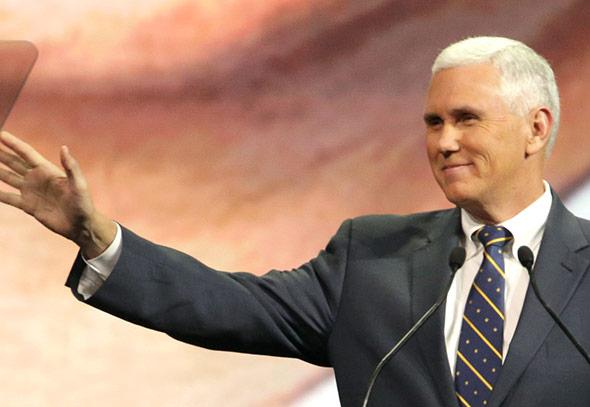

Seen from a purely political vantage, this hasn’t been the greatest week for Indiana Gov. Mike Pence, who is often mentioned as a potential dark horse for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination. For one thing, the 2016 aspirant whose profile most closely resembles Pence’s, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, is riding a boomlet following his strong performance at a conservative cattle call in Iowa last weekend. For another thing, Pence’s launch of a new government-run news service, “Just IN,” ran into so much ridicule that it was shut down well before the first issue of the Pence Pravda could hit the newsstands.

But Pence can take solace in the fact that he has this week achieved something far more consequential than these fleeting tribulations. His agreement with the Obama administration to expand Medicaid in Indiana on the state’s own terms may very likely come to be seen as a major turning point in the central battle in the implementation of Obamacare. More than that, the staunchly conservative Pence may have taken a big step toward fundamentally reshaping one of the country’s biggest safety-net programs—so much so that many liberals who generally cheer any expansion of coverage are feeling deeply ambivalent about this development.

Their ambivalence is understandable. But in the context of the extraordinarily toxic political environment around Obamacare, the Indiana news should be viewed as a step forward.

Some background: Half of the expansion of health coverage under Obamacare was supposed to come through raising the eligibility threshold for Medicaid, which varied greatly from state to state, to a uniform level of 138 percent of the poverty level—about $32,000 for a family of four or $16,000 for a childless adult. But in its 2012 ruling upholding the Affordable Care Act as constitutional, the Supreme Court also declared the Medicaid expansion optional. And many states—including most of those with the highest levels of uninsured, such as Texas, Georgia, and Florida—have rejected the expansion, even though the federal government would cover virtually the entire cost. This means that millions of low-income people remain uninsured—even as middle-class people across the country qualify for federal subsidies to help them buy private coverage—thus greatly undermining the central purpose of the law.

The Obama administration has been so eager to close this coverage gap among the neediest Americans that it has cut deals with several states—notably Arkansas, Iowa, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—to allow them to expand Medicaid in ways that differ from the traditional program. But the concessions it made to Pence and Indiana go far beyond what it has agreed to previously. The expansion will cover 350,000 people in Indiana, which previously had very stringent eligibility levels—adults qualified only if they had young children and were virtually indigent, making less than a quarter of the poverty level. But under the plan, Hoosiers above the poverty level will have to pay a monthly premium of 2 percent of their income—as much as $25 a month for a single childless adult—for coverage. Those under the poverty level won’t have to pay the premium to get basic coverage, but they won’t qualify for dental and vision benefits unless they do pay the premium. The rule will effectively create a waiting period before people get coverage, as the state determines whether they’re paying their premiums and what level of coverage they qualify for. And, in a first for Medicaid, Indiana will lock out people earning above the poverty level from their coverage for six months if they fail to pay their monthly premiums.

Hoosiers on Medicaid will also need to make copayments—including, in an another first for Medicaid, paying $25 for an emergency room visit if they’ve previously made what are deemed to be needless visits to the emergency room.

These may not sound like big sums or onerous requirements. But advocates for universal health coverage are worried that they’ll deter Hoosiers from actually seeking coverage and care, because studies have found premiums and copays, even small ones, have a highly deterrent effect on the poor, which is why Medicaid has generally steered clear of requiring them. “Medicaid was designed to make this coverage work for low-income people,” says Leonardo Cuello, director of health reform for the National Health Law Program. Judy Solomon, of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, worries that the sheer complexity of the plan—which also includes a health savings account where people are supposed to save for health costs—will keep many Hoosiers away. It’s ironic that in making Medicaid more conservative, Pence has made it much more complicated and bureaucratic: “They’re going to have thousands making these tiny contributions, and then [the state] makes tiny payments to lots of providers. The transaction costs have got to be enormous,” says John Holahan of the Urban Institute.

Most of all, some advocates worry that the Indiana model will become the model for the other 20-odd states that have yet to expand Medicaid—or worse, the starting point, as even deeper red states seek bigger concessions for themselves, perhaps by insisting on bigger premiums and copays for people further down the income ladder. Sara Rosenbaum, of Georgetown Law School, worries that the Indiana plan could even become the model for congressional Republicans if they seek a major nationwide overhaul of Medicaid—which now insures 68 million Americans—as part of some future post-Obamacare realignment of health care.

Cuello invokes the battles that followed the creation of Medicaid in 1965, when many states were also initially resistant to the program—Arizona did not accept it until 1982. What if the federal government had allowed reluctant states to chip away at Medicaid back then, instead of waiting them out on the assumption that they’d eventually join? “My concern is that over the next decade, if we’re rushing to get states in … then what we’re really doing is sacrificing the quality of what is there,” says Cuello. “Every time you make one of these concessions, you shift the goal posts. … It’s not just, was this a good decision for the residents of Indiana, but was it good for the entirety of the Medicaid program, and how it works over time and how these exceptions may be geared down the road to reduce the value of the program.”

It’s a valid concern, but the 1965 comparison assumes that the politics around the issue today are roughly the same as they were then, when the evidence suggests otherwise. The deal that many states are presented with today is, in purely economic terms, far more generous because of the near-total federal coverage of the cost of expansion. Yet so toxic has Obamacare become among Republicans that more than 20 states, including giants like Texas and Florida, are still resisting the expansion. One of the rationales for that resistance has been a classic anti-welfare distaste for giveaways: Why should people at this income level get free care when people further up the ladder are paying their fair share? This sentiment has deep and not entirely felicitous roots in many of these states, which Obamacare was intended to overcome by making coverage expansion a nationwide policy.

But the Supreme Court blew up that nationwide approach. And now the Obama administration is left looking for ways to reckon with that anti-welfare mindset. Perhaps the best that can be done for now is to meet that rhetoric on its own terms and find ways, as was done in Indiana, to make beneficiaries “pay their share,” even if those requirements do nothing but create bureaucratic hassles for the state. In effect, the Indiana plan is a way to call the bluff of holdout states such as Texas and Florida, and say: If you’re so worried about freeloaders, what about this? “One of the real sources of optimism is that some Republican governors and the Obama administration are actually negotiating and finding a dignified path for both sides so that people can actually get covered,” says Harold Pollack, a health policy expert at the University of Chicago. “The slippery slope aspect to it is concerning, and it has ratcheted up the bargaining power of other Republican governors. But a lot of people are going to be covered, and it has legitimacy from the citizens of Indiana that the Obama administration cannot provide on its own.”

He added: “If someone came and said, ‘Should we do this in Florida?’ I would say yes in a heartbeat.”

Or in Tennessee, which has been in its own negotiations with the Obama administration. Back in 2012, I visited a free weekend health clinic for the uninsured in the hills of eastern Tennessee and was truly stunned by the extent of the need on display. One of the people I met was Robin Layman, a mother of two:

Two years ago, her son, then 16, was hit head-on by a speeding driver high on drugs. Her son’s girlfriend was killed; he suffered severe internal injuries and recently underwent colon surgery. Now 18, he will soon age out of Medicaid coverage.

And Layman, a gregarious 38-year-old, recently lost coverage for her own considerable problems. She suffers high blood-pressure, for which she takes three medications, purchased at a discount from the county health office. She suffers sciatica stemming from the time eight years ago when a co-worker at a dollar store let slip a heavy box of wrapping paper Layman was handing up to her. Layman lunged for it and badly hurt her back, for which she takes the nerve-pain medication Lyrica.

She also suffers depression, and has been on Prozac for several years. But during a rough spell last fall, she came close to committing suicide. It was on her return home from a week in the psychiatric hospital that she found a letter from the state saying that, as a result of a bump up in her husband’s disability payments (he was caught in a front-end loader when he was eight years old), she was now ineligible for Medicaid.

Lacking coverage, she has not seen a psychiatrist since her hospital stay. She played this down: “I can recognize my craziness when it gets out of hand.”

It’s easy to understand the argument that requirements like the ones in the Indiana plan are going to prove burdensome for people such as Layman and others I was speaking with at that clinic. But it’s also awfully hard not to believe that for those in such dire straits, this something is a whole lot better than nothing.