In recent weeks, two grand juries—one in Ferguson, Missouri, and the other in Staten Island, New York—have failed to indict police officers in the deaths of unarmed men. In each case, the victim was black, the officer who killed him was white, and most grand jurors were white. According to a new survey by the Pew Research Center, more than 60 percent of black people, compared with 16 to 18 percent of white people, believe that race was a “major factor” in both decisions.

But the survey presents a puzzle. If race played an equally strong role in both grand juries—presumably by influencing white jurors or a white-dominated process—you’d expect the poll results to be consistent with that. Since both cases centered on a white cop and a black victim, you’d expect whites to view the two cases somewhat similarly. Instead, whites judged the case in New York quite differently from the one in Missouri.

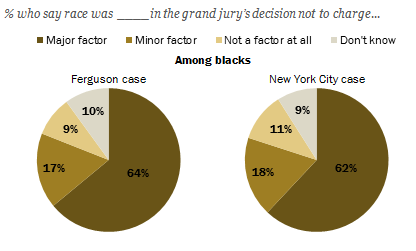

It’s a good bet that race did influence the grand jurors. Plenty of research has shown that race affects almost everyone’s perceptions, at least in subtle ways. But what’s striking here is that Pew’s black respondents believed the degree of influence was roughly the same in both cases. In the Ferguson case, 64 percent of blacks said race was a major factor in the grand jury’s decision, 17 percent said it was a minor factor, and 9 percent said it wasn’t a factor. In the Staten Island case, the numbers were almost identical: 62, 18, and 11 percent.

Pew Research Center

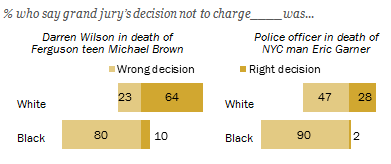

You can argue that this perception of racial bias fits what white respondents said about the Ferguson case. Sixty-four percent of whites in Pew’s sample said the grand jury was right not to indict Officer Darren Wilson in the death of Michael Brown. Only 23 percent said this outcome was wrong. Sixty percent of whites said race was a nonfactor in the grand jury’s decision. (Seventeen percent said it was a minor factor, and 16 percent said it was a major factor.)

But how, then, do you explain what the same white respondents said about the New York case? Only 28 percent said the Staten Island grand jury was right not to indict the officer who killed Eric Garner. More than half of the whites who agreed with the decision in Ferguson did not agree with the decision in New York. Same-colored victim, same-colored officer, same white poll sample, different conclusion.

Pew Research Center

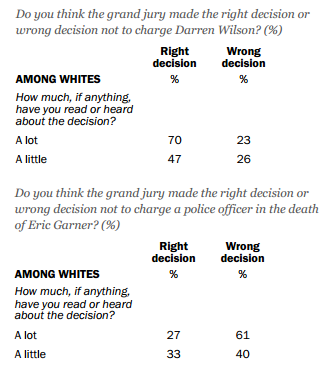

How did whites arrive at different opinions in the two cases? The crucial variable appears to be information, not race. In the Ferguson case, 47 percent of whites who had read or heard a little about the grand jury’s decision said it was right; 26 percent said it was wrong. Among whites who said they had read or heard a lot about the decision, 70 percent said it was right; 23 percent said it was wrong. That’s a 26-point increase in the net margin of support for the decision (the percentage who said it was right, minus the percentage who said it was wrong)

In the New York case, the trend went the other way. Among whites who had read or heard a little about the grand jury’s decision, 40 percent said it was wrong; 33 percent said it was right. Among whites who said they had read or heard a lot about the decision, 61 percent said it was wrong; 27 percent said it was right. That’s a 27-point increase in the net margin of opposition to the decision. In the Garner case, unlike the Brown case, the more whites learned, the more they disagreed with the outcome.

Pew Research Center

The poll doesn’t tell us what these respondents learned. The question simply asked how much they had read or heard “about the decision by [the] grand jury.” In the Ferguson case, maybe they heard about autopsy results or witness testimony. Maybe they saw Wilson’s interview on ABC News, or the surveillance tape of Brown in a convenience store. In the Staten Island case, maybe they saw the unflinching video of Garner’s death. The quantity, quality, and clarity of evidence differed between the two cases. Maybe that mattered.

And that’s the point: Evidence, not race, separated Garner’s death from Brown’s. The poll numbers don’t mean that race wasn’t a factor, or that there isn’t a lot of bias and injustice to clean up in the legal system. But they do indicate that many whites have assessed these cases based on information and that this factor has been strong enough to produce sharply different results, even when the most obvious racial factors are identical.

I wonder what Pew’s black respondents would make of these numbers. Maybe they’d point out that the legal process was tilted in favor of police in both cases, regardless of what whites tell a pollster. Or maybe they’d say that race remains a major factor in whites’ judgments, alongside information about the case at hand. But I bet that many of the black respondents would be favorably surprised and that if they were put together with the white respondents in a focus group, there would be surprises all around.

Fortunately, we don’t need a pollster to arrange that kind of conversation. We can have it right here. What do you make of the white split on the Brown and Garner cases? Does it affect your assessment of racism in this country? Why or why not?