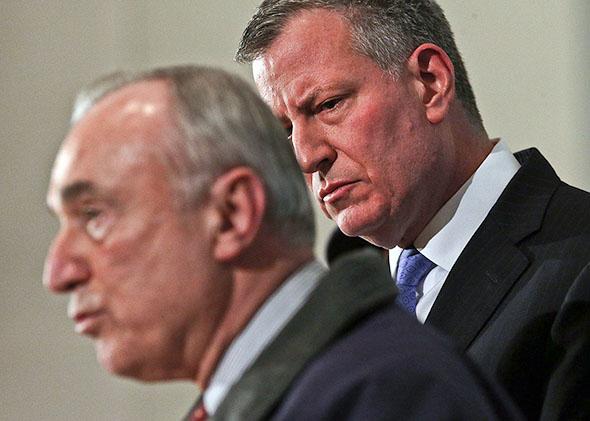

This past Saturday afternoon, two New York City police officers were gunned down in cold blood while they sat in their squad car outside a Brooklyn housing project. Within hours, the head of the city’s largest police union declared whom was to blame for the terrible tragedy: Mayor Bill de Blasio. Standing outside the hospital where the slain officers were taken, Patrick Lynch, the president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, declared that there was “blood on many hands tonight” but that it “starts on the steps of City Hall, in the office of the mayor.”

Those jarring comments followed the extraordinary decision by Lynch and many officers to literally turn their backs on the mayor as he entered the hospital. Taken in tandem, those actions cemented the perception that de Blasio’s support for those protesting the chokehold death of Eric Garner had created a rift between the mayor and his city’s police force, one that Saturday’s slayings of officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos had potentially made insurmountable.

But that’s an oversimplification of a story that’s been unfolding since long before Garner’s killing. The reality is that de Blasio and the union have been at odds since he campaigned for mayor last year on the promise to upend the city’s law enforcement status quo, including overhauling Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s stop-and-frisk program—a vow that de Blasio largely kept once in office. The police union, meanwhile, has a long history of taking public stands against New York City mayors, including law-and-order types Bloomberg and Rudy Giuliani. The relationship between de Blasio and the cops wasn’t soured solely due to the mayor’s response to Garner’s death and the subsequent protests. The mayor and the NYPD were never going to get along, no matter what.

Devoid of that context, Lynch’s remarks this weekend sounded like a rare, raw moment of candor unleashed in the heat of the moment. In reality, this was simply the latest, loudest attempt to discredit de Blasio. Lynch’s ongoing efforts to undermine the mayor were caught on tape eight days earlier at a closed-door union meeting. “If they’re not going to support us when we need ’em,” Lynch said, according to a recording of his remarks obtained by Capital New York, “we’ll embarrass them when we can.” Given the chance Saturday, Lynch did just that.

The tension between City Hall and the police union predates de Blasio by at least two decades. As former New York Times reporter David Firestone has noted, Lynch and the PBA attacked de Blasio’s three predecessors almost as vociferously. It may have seemed extraordinary when, earlier this month, the union began asking officers to sign a letter requesting that de Blasio not attend their funerals in the event they are killed in the line of duty. The union, though, tried a similar move in 1997, during Giuliani’s tenure.

The biggest difference between now and then isn’t what the police union—and Lynch specifically, who’s been president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association for 15 years—is saying. It’s that the killing of Garner and the murder of two police officers have put the strained relationship between the mayor and the NYPD in the national spotlight.

While the union’s anger with de Blasio began with his opposition to stop-and-frisk, it has grown to include a whole lot more—everything from his support for police retraining and body cameras, to the fact that his wife’s chief of staff is in a relationship with a convicted felon who once mocked police as “pigs” on social media. The mayor’s decision, in the wake of the Garner grand jury verdict, to describe how he instructed his biracial son to “take special care” when interacting with cops was the culmination of months of tension, but hardly the spark that started the current fight.

It’s not fair to say that this is all just rhetoric. There is obviously a real divide between this specific mayor and his police force. Many of the NYPD’s rank-and-file clearly feel betrayed by the mayor’s decision to have a public conversation about police reforms that the officers think should happen in private, if it happens at all. It is also clear, though, that the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association is a group that is constantly aggrieved, taking offense at slights both real and imagined. In 1992, when David Dinkins was in office, the PBA staged a rally of thousands of officers, who blocked traffic on the Brooklyn Bridge to protest the mayor’s plan to create a civilian group to look into police misconduct. “He never supports us on anything,” an officer told the New York Times. “A cop shoots someone with a gun who’s a drug dealer, and he goes and visits the family.” Sound familiar?

Underlying the tension this time around are ongoing, heated contract negotiations between the union and City Hall. That’s not to suggest that this current fight is all—or even mostly—about money. But like any employee, an officer who’s unhappy with the size of his paycheck will see it as an indication that he’s unappreciated. Toss in overblown union rhetoric about being “thrown under the bus” by the mayor, and that unease will fester.

It’s hard to tell how many NYPD officers agree with Lynch’s inflammatory rhetoric, but the perception that de Blasio hates cops has now become reality in many quarters. The last thing New York City needs right now, with citizens still angry about Garner’s death and two cops having been murdered in cold blood, is a police force that is at odds with the municipal government. But given the history of New York’s police union, it’s naive to expect we’re going to see anything else.