At first glance, the 2014 midterms look like a catastrophe for the Tea Party. Sarah Palin’s candidates lost in state after state, conservatives like Louisiana’s Rob Maness who proudly embraced the Tea Party label got walloped, and favorites of the so-called RINO surrender caucus—including Thom Tillis and incumbent Sen. Lamar Alexander—sailed to wins in their primaries ahead of their victories last Tuesday.

But movement conservative and Tea Party Republicans see it differently. They argue that their strategy for this cycle worked out fairly well—at the very least, well enough for them to see no reason to shift strategy. Prominent conservative activists who backed upstart challengers like Maness and Chris McDaniel in Mississippi are eager to push back against the emerging narrative that GOP gains in the 2014 midterms were the result of establishment Republicans’ efforts to “kick out the crazies”—for lack of a better term. In retrospect, these activists feel little regret for how the 2014 midterms played out; if anything, they feel vindicated.

Conservatives’ biggest win came early in the cycle, in the Nebraska Republican primary between former Bush administration official Ben Sasse and former Nebraska treasurer Shane Osborn. The ideological differences between those two candidates were a tad inscrutable—the two weren’t identical, but they probably had more in common than any other top primary contenders. But that race quickly became a proxy battle between insurgent Tea Party grassroots activists (there’s not a simple term to use to describe anyone involved here, alas) and often-more-moderate Washington Republicans with comparatively strong ties to business interests and less interest in ideological purity.

Sasse won the backing of the former, while Osborne captured the support of the latter. The tension between those two factions is long simmering and messy. (Jonathan Strong explained it thoroughly for National Review last year.) The short version is that Sasse won support from some of the same groups boosting Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s primary challenger. And thus, McConnell looked to bring down the hammer on the upstart. Sens. John McCain and Lindsey Graham also stepped into the fray, supporting Osborne. Sasse, meanwhile, campaigned with Sen. Ted Cruz, Sen. Mike Lee, and Sarah Palin.

The Nebraska race became a McCain v. Palin faceoff of sorts—and Palin’s side won. Tea Party leaders point to that victory as a huge moment for them.

“People can’t ignore the undercurrent that was going on in that race,” said Drew Ryun, political director of the Madison Project, a conservative group that backed Sasse.

He added that Sasse’s race was the only primary that brought together all the deep-pocketed conservative outside groups hungering to back conservative candidates in red-state primaries: Club for Growth, FreedomWorks, the Senate Conservatives Fund, Tea Party Patriots, and Sarah Palin all rallied behind Sasse, and it worked.

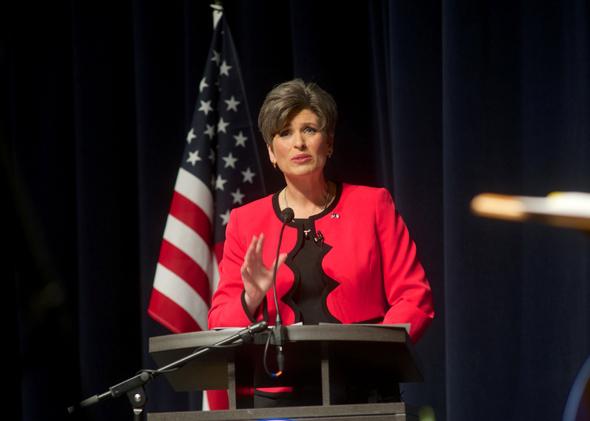

The other big primary win that outside groups claim is Joni Ernst’s, but it isn’t as clear-cut. She may be the only candidate that Mitt Romney and Sarah Palin both endorsed this cycle.

One top conservative operative said there was significant debate among conservative power- and money-brokers regarding whether to throw their muscle behind Ernst or economics professor Sam Clovis. The general consensus: Clovis was more conservative, but Ernst was more competitive.

“We just thought she had a better chance at winning the general election,” said the operative.

So they picked her. Unlike some terrible endorsement choices in their early history—Christine O’Donnell 2010, anyone?—prominent Tea Party and conservative actors decided to support the candidate who had the best shot of flipping a Senate seat long held by a progressive Democrat. It worked, and everyone is happy.

“We learned a lesson,” said the operative.

Another plugged-in conservative argues that if Ernst hadn’t won the primary, some national Republicans would have celebrated her demise.

“Winning cures everything,” he said. “Now Joni Ernst is this fantastic candidate. If she’d lost, she’s just this crazy lady with the pig ad.”

Iowa wasn’t the only race where conservative and Tea Party movers showed unusual discretion and restraint. Prominent Republicans cringed as the Georgia primary got rolling; Rep. Paul Broun, who called evolution and the Big Bang theory “lies straight from the pit of Hell,” and Rep. Phil Gingrey, who defended Todd Akin’s career-ending rape comments, both entered that contest. That could have meant catastrophe: Two hard-right, gaffe-prone, good-ol’-boy Georgians running in a contest to see who’s the most conservative—what could go wrong?

But, oddly enough, the answer was nothing. Broun and Gingrey’s candidacies never got momentum. National conservatives steered clear of them. And nobody said anything insane about sexual assault (at least, nothing that got leaked to reporters).

“Paul Broun’s poor performance vindicates the Tea Party vetting process,” said one conservative operative. “People encouraging him to run said, ‘Don’t be Akin and O’Donnell.’ And his people were like, ‘Awesome, thanks for the advice!’ ”

Most of the prominent conservative groups also gave a wide berth to Greg Brannon, a doctor who ran against Thom Tillis in the North Carolina Senate Republican primary. Sen. Mike Lee and FreedomWorks endorsed him, and Glenn Beck told him, “I could tongue-kiss you” on his radio show. But other organizations were unimpressed, and stayed out of the race. Brannon was dogged by charges that he misled two investors—you can read plenty more on that at WRAL—and was also perceived as goofy and gaffe-happy. At varying points in his career, Brannon had argued for state militias instead of a U.S. Army and floated the idea that the Articles of Confederation could be preferable to the Constitution. (Andrew Kaczynski thoroughly cataloged those insights, as well as many others.) That made it tough for Brannon to win endorsements and cash.

“Brannon just said, ‘I am conservative, raaahhhr,’ ” said one operative. “And the other guy said, ‘me too.’ It’s just that his ‘me too’ had $10 million behind it.”

“Thom Tillis might not be the most conservative person in the world, but he had to run like it,” he adds.

Thus, conservatives who didn’t back Brannon still see an upside to his candidacy. They charge that facing a competitive primary made Tillis go on the record with conservative positions on healthcare and immigration—positions they’ll be able to cite during his Senate career if he starts moving to the political center.

The same thing happened to Joe Miller, the Tea Party activist who won the Alaska Republican Senate nomination in 2010, lost when incumbent Republican Lisa Murkowski launched a successful write-in campaign, and ran again in the 2014 Senate primary.

An operative points out that Miller had paltry Tea Party backing.

“OK, we learned our lesson,” said the operative, explaining why conservative donors snubbed Miller. “He can say some crazy shit.”

On top of all that, conservatives also believe the 2014 election cycle makes a powerful case for the value of primaries as practice rounds.

“You don’t want your first fistfight to be in a general election,” said Jordan Gehrke, a Republican strategist and senior advisor to Sasse’s campaign. “It’s good for candidates to have to run races, it’s good for them to have to build organizations and have people personally invested in them, and build a massive donor list of donors who are invested. It’s good to have taken a shot to the face a couple times and have to get up off the mat to find out who they really are and what kind of candidate we really have.”

And Tuesday’s results seem to undergird that argument; Tillis, Sen. Thad Cochran, and Sen. Lamar Alexander—all of whom faced Tea Party challengers in primaries with varying degrees of competitiveness—nabbed general election wins. Meanwhile, Michigan Republican Senate nominee Terri Lynn Land and New Hampshire nominee Scott Brown—neither of whom had particularly hard-fought primary races—came up short on Election Day.

That doesn’t mean that facing a brutal primary challenge is necessarily welcome news for candidates. But it does mean that it’s not the death sentence that some national Republican strategists like to pretend it to be.

And there may be one last perk for conservatives: Republicans in Congress tend to vote a little differently around primary season. Katrina Pierson, a Tea Party activist who launched an unsuccessful primary challenge against Rep. Pete Sessions in Texas, argues that he toughened up a comparatively soft position on immigration because she challenged him.

“It’s definitely been an eye-opener for Republicans,” she said.

Whether Washington Republicans like it or not, contentious Tea Party primary battles aren’t going anywhere.