Sen. Mitch McConnell might want a more bipartisan Senate, but if Republican voters have their way, he won’t deliver one.

According to a postelection survey from the Pew Research Center, most Republicans—57 percent—think the party should move in a more conservative direction, compared with 39 percent who think GOP leaders should moderate during the next two years. Not that they’re interested in legislation. Sixty-six percent of Republicans want leaders who “stand up” to President Obama, even if less gets done in Washington. In other words, now that they have control of Congress, rank-and-file Republicans are less concerned with policy and more interested in fighting Obama, even if it derails a conservative agenda.

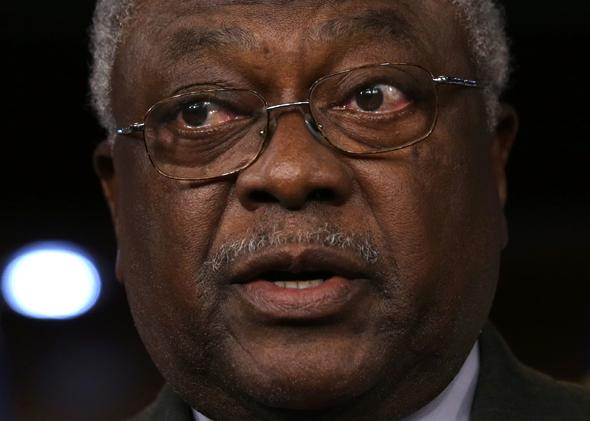

It’s this dynamic—apparent from the 2014 midterm campaigns—that prompted a dramatic prediction from Rep. James Clyburn, the third-ranking Democrat in the House of Representatives. “There will be some reason found to introduce an impeachment resolution,” said the South Carolina congressman on Tuesday on MSNBC. “These Republicans have decided that this president must have an asterisk by his name after he leaves office, irrespective of whether or not he gets convicted. It is their plan to introduce an impeachment resolution.”

Clyburn may be right that Republicans want an “asterisk” by Obama’s name. But there’s no proof of a plan. Instead, we have disavowals from a large group of Republican leaders, who all say impeachment is off the table. “We have no plans to impeach the president,” said John Boehner at a July 29 press conference. “We have no future plans.” And a few months later, just before the election, a spokesman for the House speaker told Politifact that “Boehner has taken impeachment off the table. His stance hasn’t changed.” (Indeed, he hasn’t even moved with his lawsuit against the president, a good sign that he’s telling the truth.)

If that isn’t enough to dismiss Clyburn’s claim, there’s statements from Rep. Paul Ryan, who said Obama’s actions do not “rise to the high crime and misdemeanor level”; Rep. Bob Goodlatte, who as House Judiciary Committee chairman would play a crucial role in impeachment proceedings if it happened; and presidential contenders like Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky, who, if nothing else, has a real interest in siding with the base on an issue like impeachment.

But while Clyburn’s assertion is wrong, it’s hard to say his concern is misplaced. Beginning with “birtherism,” there’s been a long campaign from the far right to delegitimize Barack Obama as president of the United States. Important examples are Donald Trump’s short-lived rise to political fame on the claim that Obama was hiding his “long form” birth certificate, and the film 2016: Obama’s America—a project of conservative provocateur Dinesh D’Souza—which portrayed the president as an anti-Colonial Manchurian candidate bent on crippling America and redeeming his father’s legacy. (It wasn’t very good, but it was awfully popular.)

These arguments weren’t embraced by Republican candidates in the 2012 elections, but they weren’t disavowed either. (The noted exception being Newt Gingrich, who asked: “What if [Obama] is so outside our comprehension that only if you understand Kenyan, anti-Colonial behavior can you begin to piece together [his actions]? That is the most accurate, predictive model for his behavior.”) Mitt Romney embraced Trump during the GOP primaries, even as the latter pushed the idea that Obama was inherently suspect.

That’s all to say that this idea of Obama’s illegitimacy lives on in grass-roots support for impeachment, which has as much traction with the Republican base as birtherism did in Obama’s first term. In a July CNN poll, 57 percent of Republicans and 56 percent of conservatives said Obama should be impeached. A more recent survey from Stan Greenberg, a Democratic pollster, found substantial impeachment support from Republicans (50 percent) and incredible support (64 percent) from the Tea Party base that drives GOP politics.

Not surprisingly, a healthy number of Republican politicians have—contrary to party leaders—expressed their support for impeachment. Last year, Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma declared, “People may be starting to use the I-word before too long,” while incoming Sen. Joni Ernst of Iowa gave the thumbs up to impeachment during her campaign for the GOP nomination in her state. Immigration hawk Rep. Steve King—also of Iowa—has threatened impeachment if the president makes moves on immigration, and South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham did the same with regard to prisoners at Guantanamo Bay.

None of this means impeachment is likely, but it does give context for Clyburn’s concern. Republican voters want impeachment, Republican politicians have talked about it, and—above all—there’s actual precedent: We’re not too removed from the witch hunt of the 1990s, where Republicans impeached a president over pseudoscandals and innuendo.

With all of that said, there’s one thing that assures we won’t see impeachment: the presidential election. Too much is on the line—including the Supreme Court—for Republicans to kneecap themselves with an impeachment fight. Then again, that was true in 1998 too, and look what happened.