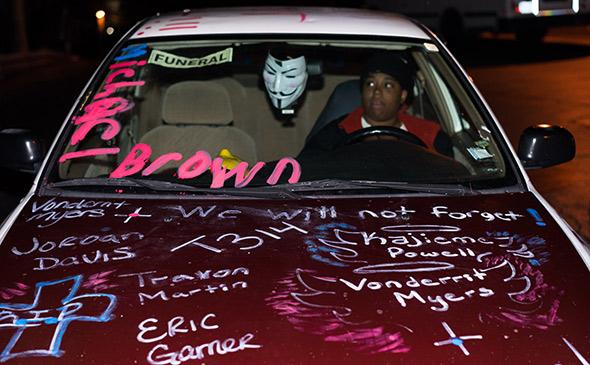

FERGUSON, Missouri—Lala’s car is the matron saint of the Michael Brown movement. The white four-door is present at almost every public protest, usually packed with young demonstrators in Guy Fawkes–style masks. A memorial tapestry has been spray-painted onto its dented surface: the names of black men recently killed by police are written on the hood; “We The People,” “Mike We Out Here,” “F.T.P,” and “No Justice No Peace!!!” adorn various panels; and in big lettering across the rear windshield, “FRONT LINE.” Arguably the protesters’ most consistently successful tactic has been stopping traffic along the roadways, but Lala’s car is allowed to navigate the streets without arousing the slightest objection. At demonstrations, it is often seen making the rounds with a full load of passengers and several additional riders sitting sidesaddle out the window or reclining on the hood.

On Tuesday night, 24 hours after the announcement of the grand jury’s decision not to indict Officer Darren Wilson for the killing of Michael Brown, the vehicle made an appearance at the memorial for Vonderrick Myers in the South St. Louis neighborhood of Shaw, for a protest organized by a group called Lost Voices. It circled the intersection, honking its horn. The protesters numbered only a dozen or two—a seemingly lackluster response to the events of the day before.

But the slim attendance in Shaw belied the energy sustaining the movement beyond the grand jury’s decision and the destruction of property that followed its announcement. What happened Monday night confirmed the public’s desire for an overhaul of the system. The scope and intensity of those demonstrations could determine how soon.

So at 9:45 p.m. Tuesday night, when a group of girls bounded down the sidewalk shouting, “Everybody go to Ferguson!” Lala’s car pulled out and led the way.

Photo by John Stillman

For a movement that is avowedly leaderless, Lala’s car may be what passes for leadership, in as much as it leads by example. Without a leader, the first person to show up for a demonstration is in charge until others join, and the decision-making begins to spread evenly among all present. The only person who can decide to end a demonstration is the one who’s last to leave. The one exception to this rule: the police.

When I returned to Ferguson Tuesday night, the National Guard was monitoring the flow of foot traffic along South Florissant Road, where most of the demonstrations and destruction had occurred the night before. Residual tear gas wafted up to the church where I parked, and a medic on the sidewalk kindly offered a pair of laboratory goggles.

Across from the Ferguson Police Department, the crowd of protesters occupied South Florissant Road, and there was Lala’s car at the center of the action. The protesters were met by a first line, comprised of state troopers in riot gear and a supporting line of combat-ready National Guardsmen.

There appeared to be an uneasy balance between the two sides, and before long, people began to loft small objects at the police line. It was never clear to me exactly where or whom these things were coming from—only that it always seemed to come from behind me. A water bottle came winging in from the rearguard and a police officer nearly succeeded in catching it.

Over the loudspeaker, a policeman announced that since things were being thrown, the protest constituted unlawful assembly, and that everyone assembled was subject to arrest if they did not disperse immediately. That order offered a clearer explanation of the boundary-line between acceptable protest and an insurrection than I’d heard on Monday night. Still, it didn’t noticeably deter the rock-throwers.

Then there began a rustling at the front—I don’t know what precipitated it. The line of troopers charged forward several paces, and the crowd scrambled backward, but not quickly enough. The police breached the protesters’ line, mace bottles drawn, and sprayed plumes into the crowd. People clamored in agony for an empty patch of pavement on which to wash out their eyes. A young man called for help as his eyes burned, but he stayed focused through the pain. “Hold the line! Hold the line! Hold the line!” he shouted. As medics surrounded him, he yelled, “No justice!” and the crowd replied in unison, “No peace!”

The allied demonstrators fanned out, their front line crumbled, and the officers briefly retreated. The parking lot was slick where the mace had fallen.

The voice of law enforcement rang out again, telling protesters to disperse or face arrest. The officers breached the protesters’ line again. The arrests that ensued were forceful, sometimes harsh. Officers hoisted their riot shields and collided with several young men on the front line, and teams of police formed around the arrestees to hold them so their hands could be cinched with plastic handcuffs. Meanwhile the other squads re-aligned and followed play-calls issued by the men who were in charge. The marched in a straight line, chanting, “Move back! Move back! Move back!” as they advanced toward the protesters.

The police continued to execute their choreographed tactics until they subsumed the parking lot in short order. The troopers then drove protesters down South Florissant Road, and as their unified front advanced, a smattering of small rocks fell at their feet. Next I heard the “click-click-clicking” of their nightsticks extending.

Then the Meineke storefront shattered, and I saw a group of five or so people fiddle with something in the window and run off. The National Guard moved to occupy the premises, hoisting their rifles and advancing with the signature crouched gait of soldiers.

The manifold forces of law enforcement pushed the willful stragglers down South Florissant to a stopper they had created out of armored trucks. We had run out of room to retreat, and the voice over the loudspeaker commanded us to go home now. I’d left my car upstream of the procession, but as I backpedaled away from the police line, I bumped into D-Red, someone who often rode shotgun in Lala’s car. He let me hop in the back seat with two other young men, Jeremiah and Deveon. They all seemed collected.

We drove away from the flashpoint and kept going until Lala steered toward a rendezvous point. Another car had left the scene when we did, driven by a man named Bishop, and Lala was on the phone with that car. She was trying to find a place we could meet up, but road closures left us fumbling around the dead-end side streets of Ferguson.

Photo by John Stillman

Lala took special care not to exceed the speed limit. She said she’d never gotten a ticket in her life until this August, when she rendered the Michael Brown tribute on her car. Since then she’s gotten 11. She grew anxious when a car with brighter-than-average headlights pulled into the lane behind us, but at the next stoplight we confirmed it was just a Volvo. Nearing 1 a.m., we couldn’t find Bishop, so we stopped for a snack and turned off the engine while we thought about where we could go to resume the action.

Then a car pulled into the lot behind Lala’s with its lights flashing. Lala was spooked. But it wasn’t the police. It was Bishop with a flashlight. I thought Lala must be paranoid, but then I realized it’s called something else when you’ve been pulled over as many times as she has in the last four months, and your lips sting with mace.

Bishop pulled his car beside Lala’s, and she tried to enlist him in her quest to continue the night. “I’m trying to finish protesting, I’m not ready to go home,” she intoned, but Bishop was ready to turn in.

“Go to bed!” he chanted. “Yes I will!”

Lala laughed. “That’s my protest tonight,” Bishop said, and even though it wasn’t what Lala’s carload wanted, it made sense considering the hour.

So she dropped off D-Red and made plans to see him at the protest scheduled for the morning, and he fetched his mask from the backseat and walked to the door. Then she dropped off Jeremiah, who grabbed his mask and went inside. Deveon lives farther away, but we agreed it was unsafe for him to walk home at this hour. “We don’t want him to get picked up,” Lala said. “We might not know what happened to him.”

“I’d probably get shot just for walking with my mask,” he said.