Despite condemnation from civil rights groups, federal officials, and the president of the United States, most Americans—including blacks—support voter identification laws. But like most public opinion, this view is highly contingent and contextual. Ask a different question—or give a different scenario—and you’ll get a different result.

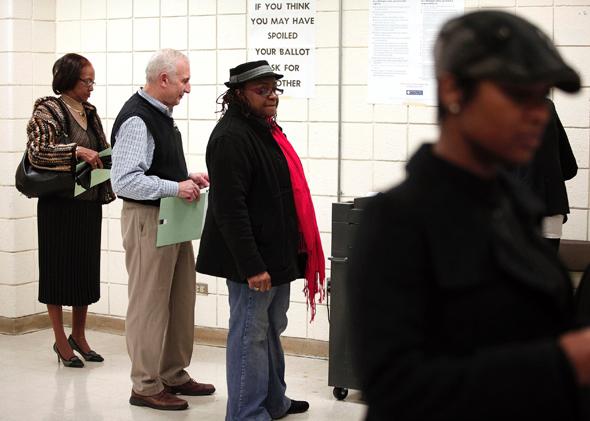

A new survey—from University of Delaware’s Center for Political Communication—makes that incredibly clear. In the study, which used a representative sample of 1,436 adults, respondents were randomly assigned to one of three groups. The first group received a statement about voter ID laws—“Voter ID laws require individuals to show a form of government issued identification when they attempt to vote”—followed by a question, “What is your opinion? Do you strongly favor voter ID laws, favor voter ID laws, oppose voter ID laws, or strongly oppose voter ID laws?” The second group received the statement and the question, as well as an image of a white person at a voting machine. And the third group received the same statement and the same question, but an image of a black person at a voting machine.

In every group, a majority supported voter identification. But while respondents in the “no image” and “white image” groups gave 67 percent support for the measures, respondents in the “black image” group gave 73 percent support.

Now, this isn’t a substantial change—from, for instance, a small plurality to a solid majority—but it is a significant one. As researcher David C. Wilson notes, “Our findings suggest that public opinion about voter ID laws can be racialized by simply showing images of African-American people. The resulting increase in support for the laws happens independently of—even after controlling for—political ideology and negative attitudes about African-Americans.” For some Americans, in other words, just seeing blacks voting increases their support for voter identification laws.

What’s interesting about this study—besides its immediate conclusions—is how it fits into an emerging picture of what motivates voter ID laws. For as much as proponents say they want to stop voter fraud and protect ballot “integrity,” more and more research suggests race as a critical factor in where these laws emerge, and who supports them.

Take a study conducted earlier this year by Christian Grose, a political scientist at the University of South California, and Matthew Mendez, a graduate student. Grose and Mendez wanted to see how bias factored into representation and constituent response—would a lawmaker who supported voter ID still respond to her minority constituents, or would she ignore them? To that end, they sent emails to legislators in 14 states with large Latino populations, asking what documentation they needed to vote. This was the email template:

Hello (Representative/Senator NAME),

My name is (voter NAME) and I have heard a lot in the news lately about identification being required at the polls. I do not have a driver’s license. Can I still vote in November? Thank you for your help.

Sincerely,

(voter NAME)

What’s important to know is that these were states where a license wasn’t needed—recipients could just answer yes and move on. One group of legislators received emails from a voter called “Jacob Smith,” while the other received email from a “Santiago Rodriguez.” What’s more, one-half of the emails were in Spanish and one-half were in English. In measuring the data, Grose and Mendez found that lawmakers who supported voter ID were substantially less likely to respond to the Latino constituent; roughly 45 percent of voter ID supporters replied to “Smith” versus the roughly 27 percent who replied to “Rodriguez.” There was a difference among voter ID opponents as well, but it was small—under 10 percent.

From this, we can’t know if bias prompted the lawmakers to support voter ID, but—as Grose notes in an interview with NPR—“It’s fair to say the Republicans who sponsored such bills seem to be biased when it comes to responding to the Latino name versus the Anglo name.”

Likewise, a 2013 study from researchers Keith G. Bentele and Erin E. O’Brien found a tight relationship between race, Republicans, and voter ID. If a state elected a Republican governor, increased its share of Republican legislators, or became more competitive while under a Republican, it was more likely to pass voter ID and other restrictions on the franchise. Moreover, states with “unencumbered Republican majorities” and large black populations were especially likely to pass identification laws.

For Bentele and O’Brien, this comes down to partisanship. “These findings demonstrate that the emergence and passage of restrictive voter access legislation is unambiguously a highly partisan affair, influenced by the intensity of electoral competition,” they write.

Even with the context of the other studies, I think this is right. Voter ID boosters don’t hold anti-minority animus as much as they want to maximize political advantage. As Judge Richard Posner wrote in a recent dissent against the Wisconsin voter ID law, “There is only one motivation for imposing burdens on voting that are ostensibly designed to discourage voter-impersonation fraud, if there is no actual danger of such fraud, and that is to discourage voting by persons likely to vote against the party responsible for imposing the burdens.”

Indeed, this ultra-partisanship helps explain the apparent reaction against minorities in the Delware and Southern California studies. If black Americans are Democratic voters and voter ID opponents, and you’re asked to take a stand on voter ID in the context of black voting, then you might show more support, if you’re a Republican voter. It’s not racial, it’s tribal.

But it’s hard to say this matters. No, voter ID supporters might not hold racial animus, but they end up in the same place as a racist who does: Supporting laws that restrict the vote and hurt minorities.