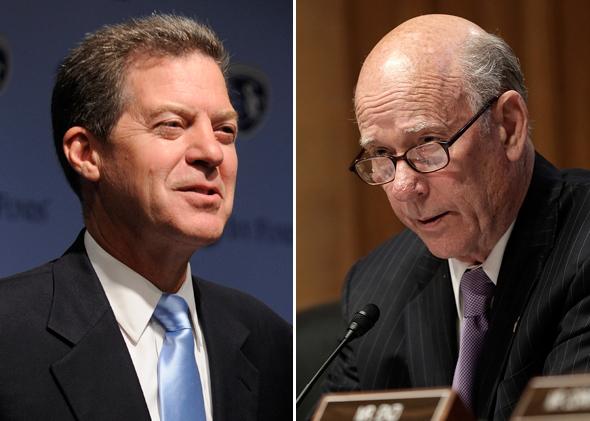

Somehow, in a year with tight, interesting races in places like Arkansas and North Carolina, the Kansas statewide contests have become the most exciting contests in the country. In the Kansas gubernatorial race, Republican Gov. Sam Brownback is losing his re-election bid to Democrat Paul Davis—the HuffPost Pollster average puts Davis ahead by 3.6 points—while GOP Sen. Pat Roberts is losing his race to Greg Orman, a multimillionaire independent whose chief appeal is that he isn’t Roberts.

Kansas isn’t a liberal place—it went 57 percent for John McCain in 2008 and 60 percent for Mitt Romney in 2012—and has a large Republican registration advantage. But barring shifts in either race, Kansas voters are prepared to dump their Republican incumbents for two challengers. And if there’s a single person to blame, it’s Brownback.

In 2010, after two and a half terms in the Senate, Brownback made a bid for the governor’s mansion. Riding the Tea Party wave, he swept his opponent in a landslide, promising a new age for Kansas politics. “[We] put forward a roadmap for Kansas,” he said in his victory speech. “It’s a plan to grow our economy, it’s a plan to create private-sector jobs, it’s a plan to excel in education, it’s a plan to support our families, it’s a plan to move forward. We campaigned on the roadmap, we won on the roadmap, we will govern on the roadmap.”

Brownback didn’t just keep his promise, he embarked on a radical “real live experiment” in conservative governance. As he later explained to the Wall Street Journal, “My focus is to create a red-state model that allows the Republican ticket to say, ‘See, we’ve got a different way, and it works.’ ”

With advice from Arthur Laffer—the long-discredited guru for supply-side economics—and support from a new band of conservative lawmakers in the Kansas statehouse, the newly minted governor pursued a path of rigid orthodoxy. His signature move was a massive tax cut: He eliminated the top income bracket of 6.45 percent, reduced the middle bracket from 6.25 percent to 4.9 percent, reduced the lowest bracket from 3.5 percent to 3 percent, and ended taxes on certain kinds of small-business income. This, he promised, would increase disposable income and create thousands of jobs.

In reality, however, Kansas’ job growth stagnated in 2012 and income growth fell. Far from a stimulus plan, Brownback’s tax cuts were a massive program of redistribution for the rich. According to a report from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, the bottom 20 percent of Kansas taxpayers saw their tax burden increase by more than half a percent as a result of the Brownback plan, while the wealthiest Kansans saw their taxes decrease by 1 percent.

Indeed, these tax cuts were followed by harsh new welfare requirements (including drug tests and stricter work provisions), and tighter eligibility for food stamps. He rejected new federal funding for Medicaid (and privatized its functions, prompting an FBI investigation), slashed thousands of state jobs, and made large cuts to education funding.

Conservative lawmakers cheered these moves, but more moderate Republicans—who held a strong presence in the state Senate—criticized the most extreme parts of the governor’s agenda. They worried tax cuts would drain state coffers, and opposed large cuts to education and social services. “I have consistently advocated for budget cuts over the last three years, but my Republican conservative colleagues can’t get enough,” said one moderate senator, who, according to the New York Times, retired rather than fight his right-wing colleagues.

Rather than work with dissenters or moderate his program, Brownback went on the offensive, aiding a wave of conservative challengers in the 2012 state primaries. Koch-backed groups like Americans for Prosperity and the Kansas Chamber of Commerce pumped hundreds of thousands of dollars into races around the state, defeating moderates and building a conservative supermajority in the state legislature.

With his power secured, Brownback turned up the heat. In 2013 he proposed another round of tax cuts that would eliminate income taxes and maintain a high sales tax. Critics blasted the plan, noting the extent to which it was a massive tax increase on the poorest Kansans: For instance, replacing 50 percent of income tax losses with a sales tax would raise taxes on the lowest earners by 2.5 percent. But Brownback promised new revenue ($777 million in state earnings) and broad prosperity. “We’re on a path of growth and job creation, so I say, ‘Come to Kansas,’ ” he said. “We’re paving the way to make Kansas the best place in America to raise a family and run a business.”

A year later Kansas is among the most dysfunctional states in the country. Even after cuts in schools, colleges, libraries, and social services, Kansas can’t keep up with expenses. This year, it faced a huge shortfall in personal income tax receipts, and had to end tax rebates for food and child care to help fill the hole. And overall, it faces a $900 million budget shortfall by 2019, even as the top income tax rate is scheduled to decline to 3.9 percent by 2018. Both Moody’s and S&P have downgraded the state’s bond rating, and economic growth has been poor. Far from giving Kansas a bright new future, Brownback plunged it into chaos.

The result for Republicans has been huge political blowback, as voters react against these ruinous policies. Paul Davis, for instance, has secured endorsements from more than 100 current and former Republican officials who oppose Brownback’s administration. And Roberts—who has his own problems with Kansas voters—has likely been harmed by this anger. Frustration with Brownback, in other words, has grown into frustration with the entire Republican ticket.

Neither man is out of the fight—there’s still enough time for the tide to turn against Davis and Orman. But it’s hard to see how. Davis continues to hold his lead, and—with the Democratic candidate officially off the ballot in the Senate race—Orman has built his.

On both ends, the implications for national politics are huge. If Brownback loses, he may discredit the “red-state way” for future Republican governors. And if Orman wins, well, there’s a decent chance we’ll have a Democratic Senate for the next two years.

In other words, while the Brownback experiment began as a move to vindicate conservative Republicans, come November, it might ruin them.