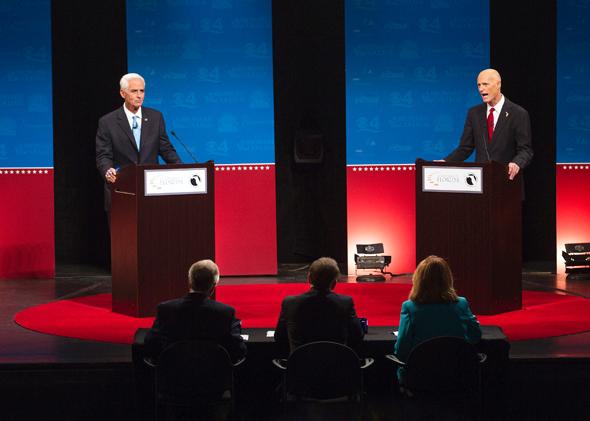

A very strange thing happened at the start of the Florida governor’s debate Wednesday night. The event was delayed for nearly eight minutes because Gov. Rick Scott refused to take the stage. The reason: His opponent, former Florida governor Charlie Crist had a fan behind his lectern. “The rules of the debate that I was shown by the Scott campaign say that there should be no fan,” said the moderator. “Somehow there is a fan there.” The audience would have been forgiven for feeling as if they had mistakenly attended Samuel Beckett’s lost play. Finally, Scott acquiesced and took the stage. Both men then immediately demonstrated why some cooling apparatus was necessary—the debate quickly became a festival of mutual contempt. Neither man was a fan of the other.

Outside of the venue, a thousand puns were launched. The laziest rolled over and called it fangate; the more enterprising labeled it the fantrum or fandango. It will pass into campaign lore as one of the stranger debate moments, but it has its origin in the most famous debates of all time, the first Kennedy-Nixon debates of 1960.

In their first debate (also the first televised political debate), Richard Nixon’s sweaty upper lip, brow, and chin supposedly did him in while Kennedy looked cool and collected. (Watch Nixon sweat here and watch him use a handkerchief to rescue himself here and here.) It was the result of a bad mix of factors. Nixon arrived at the studio already simmering with a 102-degree fever. He declined makeup when he heard Kennedy had waved off the offer. Nixon didn’t want to look less manly than his opponent. (He did send an aide to the corner store for some “Lazy Shave” to cover his five o’clock shadow. It didn’t work.)

Before the debate, Kennedy’s aide Bill Wilson had been arguing with CBS’s legendary Don Hewitt, who produced the show, for more cutaway shots of Kennedy, but that changed once the night wore on. According to David Halberstam’s The Powers That Be, Wilson started yelling in the control room for more shots of the melting Nixon while Ted Rogers, Nixon’s man, was arguing that the camera should stay focused on Kennedy.

At the next debate, the temperature was set at 64 degrees, according to a Life magazine account, in part to accommodate all the stage lights required for the broadcast. “I feel like I need a sweater,” said Kennedy. Bobby Kennedy asked: “What are they trying to do? Freeze my brother to death?” Wilson, the Kennedy aide, went to the basement to investigate because he had heard that the Nixon staff had asked for the cooler temperature and had been fooling with the air conditioner the day before to avoid the disaster of the first debate. According to Chris Matthews, Wilson found a Nixon man guarding the air conditioner. “There was a guy standing there that Ted Rogers had put there, and he said don’t let anybody change this. I said, ‘Get out of my way or I’m going to call the police.’ He immediately left and I changed the air-conditioning back.”

However, as John Kennedy said, success has a thousand fathers. Kennedy’s other television adviser J. Leonard Reinsch also takes credit for the temperature change at the second debate, telling author Mary Ann Watson, in her great book about television in the Kennedy era The Expanding Vista, “I finally located a janitor in the second basement below the studio and with a series of threats got him to locate the key to the thermostat buried in the bottom drawer of the desk. We turned the temperature up as high as we could.” (Reinsch tells this account about the second debate, not the first, as is claimed in some accounts.)

In the third debate, according to Alan Schroeder’s book on the history of debates, where Kennedy was in New York and Nixon in California, the temperature of Nixon’s studio was at 58 degrees, whereas Kennedy’s was at 72. Afterward Nixon was peeved that Kennedy had been looking at some notes, in contravention of the campaigns’ agreement beforehand. “I’m not complaining,” Nixon told reporters. “I never complain about debates after they are over. But before the next debate we had better settle on the rules.” Thus forevermore, whether it was fans, the size of the lectern, or the chairs behind the candidates, when it came to debates, campaigns would sweat the small stuff.