Willie Horton has returned, and he is in Omaha, Nebraska.

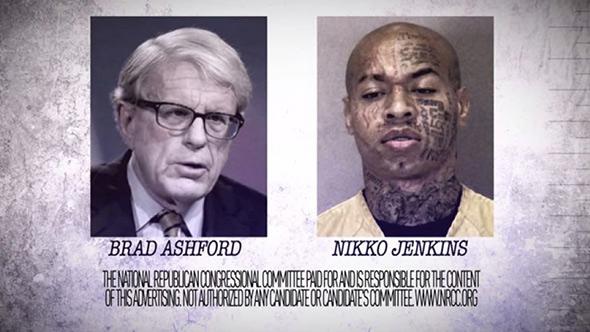

Or at least his reincarnation. Last Friday, the National Republican Congressional Committee began running an ad that hits all the beats of the original “Willie Horton” spot from the 1988 presidential election, from the attack on prison reform programs to the prominent use of imagery—violent, criminal black men—with heavy racial undertones. In particular, this ad—called “Nikko”—ties state Sen. Brad Ashford, the Democratic candidate in the Omaha congressional race, to Nikko Jenkins, a former inmate who received early release and went on to kill four people. Here’s the ad:

What’s unusual, as Dara Lind notes for Vox, is that the “good time” law was pushed by Republican lawmakers and signed by a Republican governor. It’s a GOP accomplishment, and a good one—a sensible tweak to our overly draconian criminal justice laws. This ad wants to hit a Democrat, but it feels like friendly fire. That this is the national GOP’s approach, however, isn’t a surprise.

In 2005, then Republican National Committee Chairman Ken Mehlman went to the NAACP to apologize for the GOP’s use of the “Southern Strategy” to prime anti-black views and polarize white voters on race. The implicit promise—to never again bait white voters against their black counterparts was almost immediately abandoned. In the 2006 Tennessee Senate race, the RNC ran a widely panned ad against then-Rep. Harold Ford—a black American—that ended with a young white woman saying, “Harold, call me,” which was read as a coded racial appeal.

Since then, the GOP has been in a rehab/relapse cycle with the use of race in elections. During the 2008 election, Sen. John McCain tried admirably to restrain the worst impulses of the conservative base, going as far as chastising a supporter who suggested the Democratic nominee Barack Obama was a foreigner. Most mainstream Republicans followed suit after the election, but conservative voices like Rush Limbaugh went in the other direction, embracing the crude racial language of Willie Horton and the Southern Strategy. That continued into the 2012 presidential election, with ads and rhetoric that played on racial anxiety, from Newt Gingrich’s “Food stamp president” to a Romney spot accusing Obama of taking “your” money from Medicare and giving it to unnamed others through Obamacare.

If the comprehensive RNC report on diversifying the party was the GOP’s rehab on using these messages—“The Republican Party must be committed to building a lasting relationship within the African American community year-round, based on mutual respect”—then “Nikko” is the relapse, an abrupt return to the kind of politics Republicans have condemned and promised to reject again and again. For as much as it’s tried, the GOP—or at least, some of its members—can’t quit the “Willie Horton” appeal.

But it needs to, desperately. Because of their heavy support for Democratic candidates, black voters hold disproportionate sway over Democratic chances. In national elections, for instance, high black turnout is vital: It turned North Carolina blue in 2008, kept Virginia and Florida blue in 2012, and might make Georgia a “purple” state in 2016. Republicans will never contest blacks, at least, not in the near term. But if they can boost their numbers to 10 or 11 percent of the black vote—up from 5 or 6 percent—they will have strengthened their ground in an important way. Suddenly, Virginia is more competitive, North Carolina is more red, and Democrats have to work harder in key states like Ohio.

There’s a path to this outcome. Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul has made criminal justice reform a centerpiece of his efforts, and there’s a real chance that this could reopen the relationship between some blacks and the Republican Party. With their explicit race-baiting, ads like “Nikko” aren’t just a huge step in the wrong direction, they’re an obstacle and an insult to Republicans working to build a more diverse party, and trying to reach out to skeptical black communities.