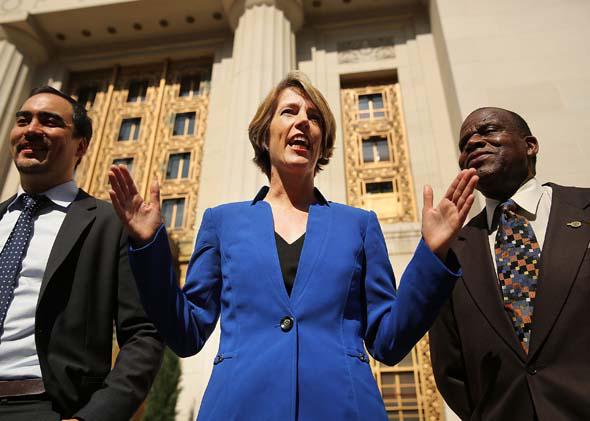

Zephyr Teachout only wanted to say hello. It was Saturday morning, the start of New York City’s Labor Day parade, four days before the Democratic primary, and Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s challenger thought she might enable their only human interaction of the campaign. The Cuomo campaign, which extends to most of the state’s governing party, had spent the day before accusing Teachout and her running mate Tim Wu of refusing to “stand strong with Israel” and—worse, perhaps—of being “professors.” (The latter charge was true.)

So when Teachout and Wu spotted Cuomo and his running mate, Kathy Hochul, they decided to greet them and move on. “We’ve been running against each other for three months now,” Teachout told me later, “and I figured it might be the last time we were in the same place together. It seemed like a courtesy.”

The blogger and reporter John Kenny filmed what happened next. Cuomo’s aide John Percoco blocked Teachout, briefly, and when he moved to wrangle cameras, Teachout tapped Hochul on the shoulder. The candidate for lieutenant governor did not respond. Cuomo looked to the side, beckoning New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio—“Where’s the mayor when you need him?”—as Teachout bit her lip. In a separate encounter, Wu was able to elicit a handshake and a “good to see you!” from his governor, as Rep. Carolyn Maloney, one of the Democrats who’d accused the challengers as not “clear about their support for Israel,” spoke sotto voce to Hochul.

For at least the second time in a short primary season, Cuomo had made an unforced error and gifted Teachout with free media coverage. Previously, instead of ignoring an opponent that had run no TV ads and raised a fraction of his $30 million, Cuomo backed a legal challenge to Teachout’s residency. The result: A surge of free media for Teachout.

This time, instead of a mostly harmless photo of two candidates making nice, New York media got a story about a hubristic, brittle incumbent acting like a Mean Girl. He was asked about The Diss at three successive press conferences.

“Tim Wu said you failed a basic test of decency,” said one reporter at an event in Midtown.

“I never saw her,” said Cuomo. “If anything, I failed an eyesight test.”

Cuomo’s failure, if that’s what you want to call it, will make Tuesday’s primaries an unexpected test of explicitly progressive, explicitly “anti-corruption” politics. In New Hampshire, Harvard professor Larry Lessig’s Mayday PAC has spent more than $1.6 million to promote Jim Rubens, a conservative Republican running on campaign finance reform, in a primary against Massachusetts immigrant-turned-Senate candidate Scott Brown. In Rhode Island, progressives have complicated—but may not squelch—the ambitions of a Democratic candidate for governor who made her name by cutting state pensions. In New York, Teachout has become a phenomenon, with fellow veterans of the Howard Dean presidential campaign, celebrities, and even the New York Times buying into her case against Cuomo.

The Times did not actually endorse Teachout (it did endorse Wu), but it gave her campaign theme a crucial assist. She and Wu were in the race, but getting little attention, until a blockbuster July story in the Times revealed how Cuomo had created an independent commission to investigate corruption (“The politicians in Albany won’t like it!”) and shuttered it when it got too close to his own Dumpsters.

Still, the press does not automatically spend time on primary challengers with little money and no polling that says they might win. Cuomo’s hubristic attacks on Teachout—who, to date, he has not mentioned by name—backfired completely, and according to people familiar with internal polling, Cuomo might lose more than 30 percent of the vote to a first-time candidate. For comparison, in 2006, Hillary Clinton lost only 19 percent of the vote on her left flank to Jonathan Tasini, a writer and organizer who attacked her then-raw vote for the war in Iraq.

Teachout has used her moment to talk about the very nature of government and how people interact with it. The Internet, she says, creates giant-killing networks that traditional power cannot see coming, and cannot stop—the “fracktivists,” for example, who want to leave natural gas in the ground. “New York State was supposed to have hydrofracking just like every other shale-rich state,” Teachout told reporter Nancy Scola last week. “And they stopped it, without Big Green, without big national politicians, without mainstream media. They stopped it through a network of listservs, really.”

Lessig’s PAC had not planned to endorse Teachout. Mayday was targeting federal races. But on Aug. 13, Lessig asked Mayday supporters to back Teachout, “the most important anti-corruption candidate in any race in America today.”

“He is our (Democrats’) Nixon,” Lessig described Cuomo this week, after the Diss video went viral. “Why can’t we make him our Eric Cantor? Because to revive this democracy enough to give anyone under 40 a reason to care would require as much. In a literal sense of the word, it is possible. There are more than enough New York Democrats connected to these tubes to defeat Cuomo.”

Meanwhile, just north of New York, Lessig’s PAC and its supporters were trying to elect a Republican senator. Jim Rubens, a former state senator in New Hampshire, had been floating in the single digits and collecting endorsements from conservative and libertarian groups. Mayday’s spending gave him a race. In a Public Policy Polling survey conducted the week before the primary, Scott Brown led Rubens by a 53-24 margin and 71 percent of Republicans agreed that a candidate in favor of “reducing the amount of money in politics” would get their votes. (Bob Smith, an unpredictable former senator who moved to Florida for a while, is also in the race.)

That did not happen overnight. Lessig met Rubens on Oct. 23, 2013, at an event sponsored by the anti-corruption New Hampshire Rebellion. “Larry Lessig and I batted some ideas back and forth before he started Mayday,” Rubens told me. “I passed my concept of the voucher system, a tax rebate that could be spent on campaigns, and he was kind enough to provide me comments. So I polished that idea up a bit.”

Like Teachout, Rubens got a boost from his opponent’s out-of-nowhere hubris. Mayday’s buy in New Hampshire included mailers to Republican voters informing them that Scott Brown was a “former Washington lobbyist” who “refuses to sign a pledge limiting special interest money in elections.” Two days before the primary, Brown’s campaign issued a cease-and-desist letter to Lessig, which it shared with reporters. That did not succeed in stopping the ads. It succeeded in reviving the question about what Brown did when he became a “business and governmental affairs” expert at a lobbying firm. Within a day, reporters armed with shaky cameras were getting on Brown’s nerves about this.

But Brown’s likely to win. So is Cuomo. So is Gina Raimondo, Rhode Island’s treasurer, in a race that progressives worry that they could have won. In a September 2013 profile by Matt Taibbi, progressives outside Rhode Island got to know Raimondo as the ambitious Wall Streeter who handed 14 percent of the state’s pensions to hedge funds. Her Gov. Chris Christie–style campaign of real-talk town hall meetings, where she sold her plan to raise the retirement age and cap cost-of-living adjustments for pensions, was bolstered by $700,000 from a mysterious group that folded as soon as Raimondo succeeded.

This was a candidate progressives wanted to make into an example. Raimondo’s strongest challenger appeared to be Angel Taveras, Providence’s mayor, who went after the front-runner by relentlessly attacking financiers. “Wall Street values?” asked Taveras in one of his first ads. “They make money off of your hard work. I believe we’re all in this together.” In his closing TV ad, Taveras repeated that “pensions need to be protected from Wall Street.”

But Taveras did not get a one-on-one race against Raimondo. Clay Pell, the grandson of the senator best known for his eponymous Pell grants, jumped into the race with a standard “outsider” pitch. Taveras and Raimondo fought over the specifics of pension reform, with trade unions generally getting behind her as AFSCME got behind the mayor. Teacher’s unions, which (understandably) soured on Taveras after he fired every teacher in the city, sided with Pell.

The result may be a Raimondo win. The struggles she had—like Cuomo’s struggles, like Brown’s sudden irritation—represent a new kind of reform politics that got a late start this year. No problem. There’s always another election.